Cambridge boat sinks — at chess

(Alamy)

The annual chess match between the teams of Oxford and Cambridge Universities, the Varsity match, has often been described as the Boat Race of the Brain. This year, the Cambridge boat sank, with almost all hands. After 139 matches the overall score now stands at: Cambridge 60 wins, Oxford 57 and Drawn 22, which is at least some consolation for the University which holds the world record for Nobel Prizes, 121 – with my own Alma Mater, Trinity College, retaining the internal Cambridge laurels, with 34 (plus Sir Isaac Newton, who would surely have been the greatest laureate of them all.)

From 1959, I studied modern languages at Dulwich College, and in 1966 I had to decide on my university application. It was clear that Jesus College, Cambridge, with that outstanding talent, Bill Hartston (who went on to win the British Championship, twice) on top board, could boast the strongest chess team of any UK university, with Trinity College in second place. I therefore resolved to apply to Trinity, with the goal of transforming it into number one in chess.

I had, though, overlooked one hurdle: Trinity was one of the few remaining colleges which insisted on scholarship applicants also passing an examination in Latin, notably a non-modern language, and one which I had ceased studying at O Level (the prehistoric equivalent of the modern GCSE), some years before the scholarship tests. Another problem was that I had spent most of the preparatory scholarship term representing England in the Havana Chess Olympiad of 1966, dining with Fidel Castro and narrowly missing the chess loving Che Guevara. Not much time for reviving my knowledge of amo, amas, amat and Veni, Vidi, Vici.

Returning from Havana, and with only a couple of days to forget chess variations and revive my Latin grammar, I arrived at the examination hall with a certain degree of trepidation. I opened the exam paper to discover that I was being invited to translate Quintus Horatius Flaccus ’ Carmina 4, Poem 7 . Fortunately, I recognised this poem as Horace’s Ode to Spring, and to my intense surprise, not to say relief, I was now faced with the extraordinary coincidence of being asked to translate the only Latin poem I knew by heart, both in the original Latin and in English translation. (It can be found in full here .)

Diffugere nives, redeunt iam gramina campis

arboribusque

comae…

The snows have dissolved, the grass has returned to the fields

And the leaves to the trees…

So… 100 per cent marks and next stop, Trinity College, Cambridge, to study French and German, but with the ulterior motive of dethroning Jesus College and placing Trinity College at the top of the Cambridge chess tree.

This year’s match between Cambridge and Oxford, normally held in spring, had been postponed because of the pandemic. It eventually took place with a six-month delay on Saturday, October 23, 2021. In what follows I would like to express my thanks to Stephen Meyler and the Chess Committee Members of the hosting Royal Automobile Club, the RAC, for their extensive and insightful comments in the excellent programme for the event.

According to the programme, the idea of a regular chess match between Oxford and Cambridge Universities had first been suggested in 1853 by English polymath and unofficial world chess champion, Howard Staunton. In 1871 the Oxford University Chess Club challenged Cambridge to a match, but at that time, the Cambridge Club was only open to dons, who declined the challenge from the undergraduates. Not until 28th March, 1873, did the first official over-the-board Varsity Match take place, at the City of London Chess Club. Since then it has grown into the oldest continuous fixture in the chess calendar, interrupted only by war years. The winning team is awarded, to hold for a year, a handsome gold cup, originally presented in 1953 by Miss Margaret Pugh.

A women’s board was introduced in 1978 to determine the result in the event of a drawn match. However, since 1982, it has been decreed that the matches should comprise eight boards, with at least one woman player in each team, the board ranking being determined solely by playing strength. To emphasise the essentially undergraduate nature of the competition, all players must be resident

bona fide

students of the universities, with at least three members of each team studying for a first degree.

During the 20th century, it was remarkable how many British Champions had played in the Varsity match. In addition to those named below, Henry Atkins, William Winter, Alan Phillips and Hugh Alexander (who worked with Alan Turing to decipher the Nazi codes in World War II) played for Cambridge, with Leonard Barden, Peter Lee and George Botterill representing Oxford. A feature of recent years has been the increasingly international nature of the teams, reflecting the student intake of the universities.

Looking at the history of the match, Cambridge retained the lead in the series until 1956 when Oxford won 4–3, with the impressive and seemingly immortal Henry Mutkin winning on Board 2 for Oxford. Then Oxford went ahead until 1970 when Cambridge — inspired, as the RAC Committee generously remark, “by the presence of Raymond Keene and Bill Hartston” — began a remarkable run of 11 straight victories. In their wake came a procession of first-class Cambridge players, including Welsh champions Howard Williams and John Cooper, Grandmasters Michael Stean and Jonathan Mestel (both Trinity, by the way), as well as International Masters Paul Littlewood and Shaun Taulbut. Although Oxford had its stars too, including Grandmasters Jon Speelman and John Nunn, together with International Masters Andrew Whiteley, George Botterill and Peter Markland, Cambridge had greater strength in the lower boards. However, in 1981 the tide turned and Oxford achieved a run of eight consecutive victories, eventually regaining the overall lead.

In 1973 the event was held for the first time at the Royal Automobile Clubhouse in Pall Mall, London, for the Centenary match. By invitation of the Royal Automobile Club Chess Circle Committee, the match has been played each year at this ideal venue since 1978. The Committee’s Honorary President, the indestructible Henry Mutkin, also present for this year’s match, captained Oxford on top board in 1957 and has been a driving force of the event to the present day. Other officers of the Committee are Chairman Henry McWatters, Match Captain Robert Matthews and Honorary Secretary Richard Hughes. Again, thanks for their erudite comments on the history of the contest, and their highly useful comments on the run of play in the latest bout.

For the 139th Varsity Chess Match any predictions, based on respective ratings, of a close contest did not come to pass, with Oxford moving swiftly to establish a 3-0 lead, the match eventually ended in an overwhelming 5½–2½ victory for Oxford – with only one game being drawn. Special prizes were offered by artist Barry Martin, while the concert pianist Jason Kouchak, resplendent in a replica of the frock coat of his ancestor, a Czarist admiral, delivered post-prandial entertainment.

The Brilliancy Game Prize (meaning in essence, the game with most sacrifices) was awarded to Board 2, where Filip Mihov overcame Koby Kalavannan, while Oxford’s winning captain, Victor Vasiesiu, was, in addition, awarded the Best Game Prize (the most accurately played) for his win against Daniel Gallagher. Grandmaster Jon Speelman and I formed the judging panel. Although the chess columnist of TheArticle was in deep mourning at the Cambridge rout, our Editor, Daniel Johnson, an Oxford alumnus, was able to celebrate a glorious victory.

The trophies and prizes were awarded at a gala dinner in the monumental Mountbatten Room at the RAC. All games can be found here on www.lichess.com.

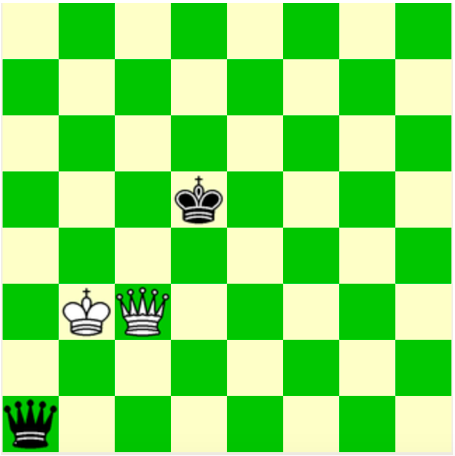

Last week ’s column has provoked a number of questions, which I hasten to answer. First, was the great Arabic master of Shatranj, As Suli, really known as a Grandmaster? The exact term used at the time was Aliyat, which has the same connotation. Next, As Suli’s celebrated puzzle, (known as As Suli’s Diamond) please see the following diagram:

As Suli’s Diamond Puzzle: White to move.

Remember that in Shatranj, the ancestor of modern chess, the King has the same powers as now, but the Queen (known then as the ‘ Vizier ’) could only move one square diagonally in each direction. White is to play and win, which could be achieved in Shatranj by taking all of your opponent’s pieces, in sustainable fashion, not just by delivering checkmate. The Black Vizier is trapped in the corner, but any crude attempt by White’s King to hunt it down, will be parried by an equalising counterattack by the Black King against the White Vizier. Capturing Black’s Vizier on one move, only to have Black capture White’s Vizier on the next turn, does not count as a win. The art is to capture the Black Vizier, while permanently preserving the life of the White Vizier, thus ensuring victory. This problem remained unsolved for 1,000 years until Russian Grandmaster Yuri Averbakh (about whom I wrote here last February) cracked the puzzle. For those interested in seeing Averbakh’s solution, please see the link here .

Raymond Keene’s latest book “Fifty Shades of Ray: Chess in the year of the Coronavirus”, containing some of his best pieces from TheArticle, is now available from Amazon , and Blackwell’s .