Global governance after Afghanistan: Biden’s America, post-Merkel Europe and the BRICs

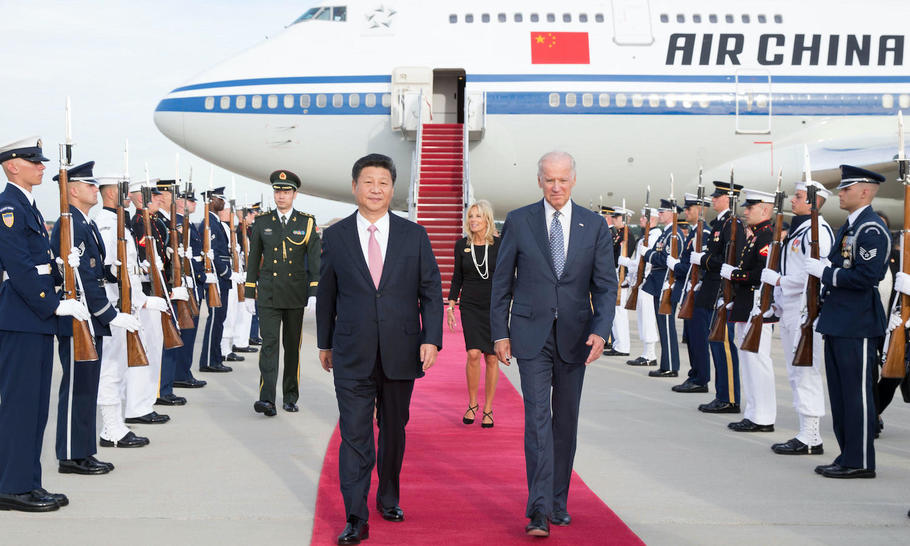

President Xi Jinping and Joe Biden (Huang Jingwen/Xinhua/Alamy Live News)

After the retreat from Afghanistan a central question , at least for the liberal chattering classes, is: what are the consequences for the US and its Western allies? What does this seemingly meek exit from Kabul mean? For a considerable number of people, maybe it doesn ’ t mean anything, as neither the military presence there nor the retreat impacted their lives, at least superficially. This perception might explain why President Biden made his decision. He wants to get beyond this moment of public embarrassment and shift the focus to things that might matter more to him, including American domestic affairs and the rise of China.

I wrote about this here in a Project Syndicate piece last month, especially as it relates to the role of the US dollar. To my mind it is not entirely clear why the humiliation in Afghanistan should have more lasting consequences than the failure of Western attempts to impose their democratic will in Vietnam, Iraq and Libya, to highlight just three episodes. Indeed, perhaps for key aspects of controlling adverse risks emanating from untrustworthy states, financial means, including the powerful role of the dollar, might be seen as a more useful tool. We saw indications of this thinking under Trump, where the US strongly used the dollar’s huge role at the centre of the financial intermediary system to penalise Iran, Russia and, at times, other states perceived to be hostile.

In this regard, a more central, bigger question, coinciding with the Afghan debacle, is: what is going to be the ongoing role of the US economy, and with it, or indeed separately, the role of the US dollar in the world economy and its financial system? Ultimately, this is where the US has maintained such a massive influence throughout the past 50 years of the post Bretton Woods architecture, despite the rise of other economies, and by default, the relative, if not absolute decline of the US economy.

This is an especially prescient question for me, as this November will be the 20th anniversary of when I first coined the acronym “BRIC”, to represent the emergence and probable rise of the economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China — something itself that was partially prompted by the events of September 11, 2001. If, as the subsequent 2003 paper showed possible, by the mid 2030s the combined GDP of those four countries became as large as that of the G6 (the G7 minus Canada : for some reason, we decided to exclude Canada due to its relatively small size), presumably the circumstances of the governance of the world economy including its financial structure might not be quite the same. Or, given the continuity of global governance over the past 20 years, notwithstanding the economic rise of China and India, will the role of US and its dominant financial system remain broadly similar to that of today?

My most confident answer is: “ Who knows?” But I keep an open mind. To determine the answer, it seems to me there are essentially four interrelated questions to consider, each of which relates to the others, with their own subdivisions of questions. Some of those, especially given the 20th anniversary of the BRICs, I shall be returning to in coming weeks.

The first concerns the future of the US economy. I recently presented a three-part radio series for the BBC about this question, especially in the context of the pandemic and the ambitious fiscal plans of the Biden Administration. I concluded by saying that all those who have written off the US economy when it is faced with big challenges during my adult lifetime have lived to regret it — at least so far. What is clear is that Biden has taken huge risks with the US fiscal position. If the so-called multiplier of this spending fails to lift the trend rate of growth of the economy, then it will certainly raise persistent questions about whether the stimulus was worthwhile, as well as how and who is going to pay for it. Worse, if Biden’s plans fail, they might accelerate a relative decline of the US, as this could set the scene for persistently tighter fiscal policy in the future, especially if inflationary pressures turn out to be persistent and real.

The second question is about post-German Europe, the future of the EU, and within that, the Eurozone. Due to its population and economic size, the Eurozone does have the potential to be much more influential on the global economic scene, with the Euro playing an instrumental part in the future of the financial system. The end of 16 years of Angela Merkel’s rule does raise the possibility that a future German government might be more open to playing a bigger leadership role in the world economy, perhaps supporting the idea of a financial instrument to manage collective risk across the Euro area. Could this mean a bigger role for the Euro? Now, my slight bias would conclude that, while this is still unlikely, the chances are higher than at any time since the Euro was first conceived. And if such an enhanced role for the Euro were to emerge, this would certainly hasten a lesser use of the US dollar, especially in neighbouring countries and regions and possibly beyond. In such circumstances, a future crisis equivalent to Afghanistan might result in a bigger fallout.

A third question is the whole future of the BRIC countries, which again has many subplots. Will Brazil and Russia be able to recover from their dismal second decade of BRIC status, and repeat what happened in the first decade, when their respective shares of global GDP rose notably? (Today, they are both back to where they were in 2001.) Towards the end of the first decade, Brazil was briefly the 7th largest economy in the world, and Russia just behind it. Today, Russia is outside the top 10. Measured by purchasing power parity (PPP), at the end of 2020 Brazil’s economy was smaller than Indonesia’s. If Brazil and Russia do recover, then without disasters for China and India, it is very likely that the collective BRIC economic might will surpass that of the G7 before 2040. On balance, I would say that it is doubtful whether either Brazil or Russia can rediscover that Noughties zest, not least as it is tough for the precise conditions of the commodities boom that they then enjoyed to be repeated.

However, it remains the case that, because of the ongoing growth of China, even if Brazil and Russia languish, the collective size of the BRICs could still exceed the G7 before 2040, simply because China becomes as large as the US, India as large as Japan, and then the relative weaknesses of Brazil and Russia would be no more relevant than the relative weakness of Italy. In these circumstances, it would really boil down to the question: what does China want, or what will it perhaps evolve to want, on the global scene?

Which brings me to the fourth question: will China and its BRICs friends (although India often seems to be anything but) want to truly influence the global financial system and crucially, contribute more responsibly towards it? While it is currently popular to argue that China and Russia are the winners from the Afghan fallout (and there has certainly been some clever diplomacy from each to this effect), are they really going to contribute to a better system of global governance, with its economic and financial rules, and to a new modus operandi ? The first few years of President Xi ’ s big priority, One Belt One Road, haven’t really shown any true signs of success. Indeed, China’s fellow BRIC, India, has consciously declined to participate. It will take a much more imaginative and outward-thinking China, capable of adding to its future domestic economic power, to reduce the default dominance of the US-based global system. That, at least, is what I currently think.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout the pandemic. So please, make a donation.