Is Boris Johnson a Keynesian?

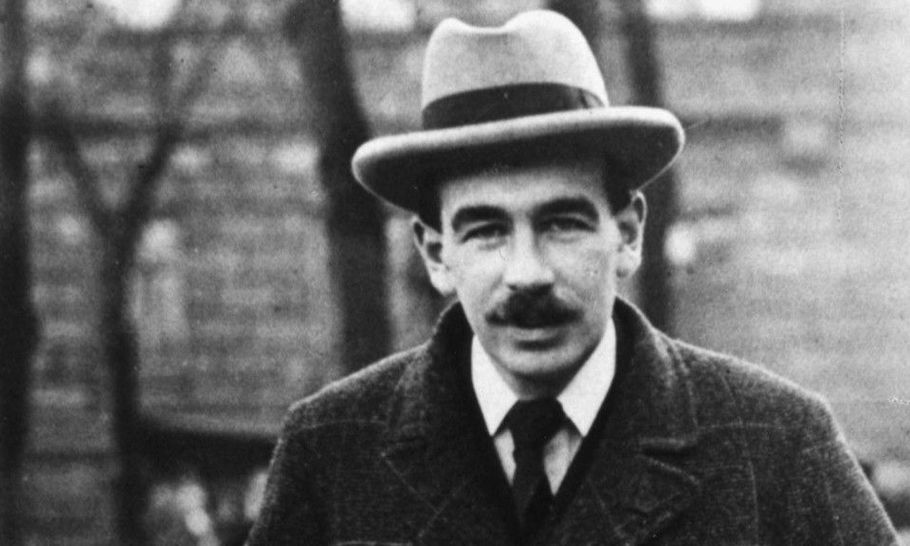

John Maynard Keynes

All would-be Prime Ministers know the power of the “feel-good factor”. Boris Johnson is no exception. It is reported that he is planning an emergency Budget in September to stimulate the economy in anticipation of the shock of a no-deal Hallowe’en Brexit.

According to these reports — some of which come from the horse’s mouth, others from inside his camp — the total size of this stimulus package could be as great as £30 billion. The combination of tax cuts (income tax, national insurance, stamp duty, business taxes) plus public spending (police, schools, roads, railways, universal full-fibre broadband) is intended to boost consumption, investment and growth.

Is such a stimulus required? Over the past three years, anxiety about Brexit and terror of a far-Left Corbyn government have sapped business confidence. These factors, along with George Osborne’s near doubling of stamp duty on properties over £1.5 million, have also depressed the all-important housing market.

Growth has slowed, though never to the point of recession; and though economists disagree about how great the impact of Brexit will be, there is a broad consensus that some sectors of the economy will be hit hard by loss of access to the Single Market and the removal of subsidies such as the CAP. The City of London is braced for a major shakeup as it loses “passporting rights” in the EU. A radical free trade policy of the kind advocated by some Brexiteers would also remove protection from those that have been sheltered by the Customs Union. And a no-deal Brexit would mean tariffs on exports to the EU, even if the UK chose not to impose reciprocal tariffs on EU imports.

Hence Boris has a cunning plan to ensure that by the time Britain finally leaves, the economy will be “going gangbusters”. On this, if on nothing else, he sees eye to eye with the Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, who has indicated that he is likely to cut interest rates to compensate for the expected downturn.

But if the Boris plan involves cutting taxes while simultaneously raising spending, where will the money come from? The answer, in the short term, is that Boris will borrow. Despite a decade of so-called austerity, government debt remains stubbornly high by historic standards, at about 82 per cent of GDP. Though the UK lost its coveted triple-A credit ratings after it voted for Brexit, the only obstacle to raising public sector net borrowing is the annual cost of interest repayments, now running at about 2 per cent of GDP. This is a heavy burden, but during the late 1970s and early 1980s, that figure rose to 4 per cent without the sky falling. As Adam Smith said, there is a deal of ruin in a nation.

Boris is nothing if he is not bold — some would say profligate— with other people’s money. He will expect nothing less from his Chancellor, who in all likelihood will be Sajid Javid (assuming he wants the job). Their hope is that a surge in economic activity, coupled with Trump-style deregulation, will generate enough growth for the tax cuts and spending splurge to pay for themselves. By the time the effects of the Boris boom wear off, Brexit should have begun to bring benefits as well as costs. Britain will become Europe’s Singapore, on a much grander scale.

One aspect of this rosy picture has, however, been overlooked. Boris may fancy that he would repeat the success of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, but he is basing his plan on a very different body of ideas. Mrs Thatcher’s intellectual heritage was that of classical economics, as interpreted by the monetarists Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. They saw free markets, not central planning, as the solution. And they warned against the influence of Keynesian economics, which they believed had brought about economic stagnation and chronic inflation at the same time.

Boris, by contrast, appears to be a disciple of the monetarists’ bête noire. He believes, as Keynes did, that almost any economic activity will act as a “multiplier” and that such activity must be maintained at all costs, by public spending and borrowing. In his masterpiece, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Keynes made the case for state intervention to prevent the kind of slump that had led to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Boris Johnson is now preparing to pull every interventionist lever that he can to stave off such a post-Brexit slump — just as Gordon Brown did in 2008. The only difference is that Brown is proud to call himself a Keynesian, whereas Boris poses as a Thatcherite.

In the conclusion to his General Theory, Keynes wrote one of the brilliant passages that make him still so influential: “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.”

Could it be that Boris Johnson — whether he be practical, impractical or even a madman — is the slave of John Maynard Keynes himself, an economist who has been defunct for three quarters of a century?