New York 1924: a stellar gathering

back row: (left to right): Marshall, Tartakover, Maroczy, Alekhine, Reti, Bogoljubov front row (left to right) : Yates, Capablanca, Janowski, Ed. ...

“There’s this monstrous idiot — this monstrous elected idiot — who keeps telling his fellow-idiots to throw my books on a bonfire and beat me up In the street…”

The author of these words was Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) and I first read and transcribed them six decades ago. He was the Austrian-Jewish émigré author of Schachnovelle (variously translated as “The Royal Game” or “Chess: A Novel”) and the popular history book Sternstunden der Geschichte (“Stellar Moments in History”), which I first read at the age of 17. It felt particularly poignant to inscribe on the flyleaf of a Zweig masterpiece a message about the suppression of writers. He was one of many whose opinions and style have unexpectedly fallen foul of those controlling the levers of publication, and, fatally, those of government and power. But his fate at the hands of the Nazis was a particularly tragic one.

Stefan Zweig was one of the world’s most successful authors: widely read, universally admired, and translated into every language. His was the life of a wealthy playboy, enjoying only the finest things in life — from luxurious world travel to the company of his most dazzling contemporaries in Europe’s most fashionable restaurants. Only one obstacle clouded his prospects: the rise of the Nazi Party, which ultimately drove Zweig to abandon his beloved Vienna for the successive havens of the UK, the USA and finally Brazil. There, in 1942, in a fit of despondency at Hitler’s seemingly irresistible rise to success, Zweig committed suicide.

The book that made such an impression on me, Sternstunden der Menschheit (“Stellar Moments in World History”), is an unforgettable masterpiece. Zweig’s other passion, apart from writing, was chess. If there are Sternstunden der Schachgeschichte , stellar moments in chess history, then the New York tournament of 1924, exactly a century ago, certainly merits inclusion.

This was a stellar gathering indeed, and a turning point in chess history too. The sensation of the tournament was the then World Champion José Raul Capablanca’s uncommonly bad start. This was so unlike his customary clockwork precision, which had enabled him to defeat the great Emanuel Lasker three years before in Havana without loss.

His scoring a mere draw in each of the first four rounds was still considered his methodical way of “warming up” for so long a tournament, but the real sensation came in the fifth round when the World Champion lost to Richard Réti. It was Capablanca’s first defeat for many a year, and as for the tournament score it meant that with two points out of five he was well behind in a very strong field. However, far from discouraged by so catastrophic a start, the champion now showed his mettle by scoring 10 wins and five draws in the remaining 15 games.

However, he had Emanuel Lasker to contend with, and even that splendid recovery wasn’t good enough to catch up with such an adversary. For this time, unlike their match in 1921, Lasker was in splendid form from the beginning. His loss to Capablanca in their second game had little bearing on the result, as it was his only loss in the tournament. Since he merely gave away six half-points and scored 13 wins, Lasker finished with the magnificent score of 16 points (80 %!), 1½ points ahead of Capablanca who, in turn, was 2½ points ahead of Alekhine and the rest. (My thanks to Dr J Hannak for the above information. (Hannak’s biography, Emanuel Lasker: Life of a Chess Master, is preserved in print by Hardinge Simpole Publishing.)

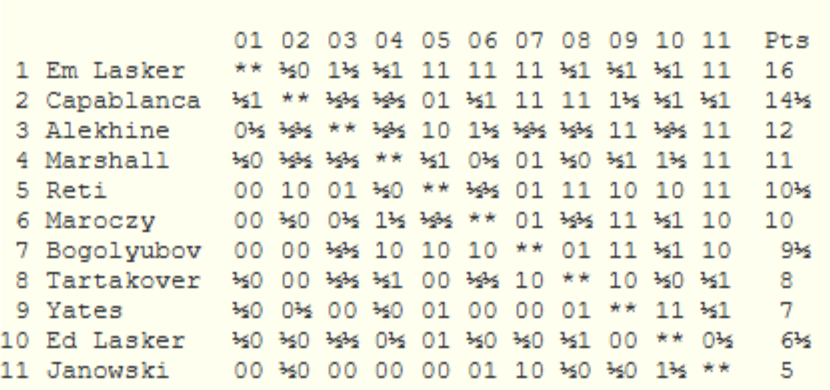

New York 1924

Many of these games reward an appreciative player; check out the following:

Richard Réti vs. Jose Rául Capablanca

Alexander Alekhine vs. Emanuel Lasker

Jose Rául Capablanca vs. Emanuel Lasker

Frank Marshall vs. Efim Bogoljubov

But of all these fine contests, one stood out to win the brilliancy prize:

Richard Réti vs. Efim Bogoljubov

New York International, rd. 12, 1924

Notes by Alexander Alekhine

1.Nf3 Nf6 2. c4 e6

As for the merit of this system of defence, compare the game Reti vs. Yates in the sixth round.

3.g3 d5 4. Bg2 Bd6 5. O-O O-O 6. b3 Re8 7. Bb2 Nbd7 8. d4

To our way of thinking, this is the clear positional refutation of 2… e6, which, by the way, was first played by Capablanca (as Black) against Marshall and is based upon the simple circumstance that Black cannot find a method for the effective development of his Queen’s Bishop.

8… c6 9. Nbd2

In the game referred to, Capablanca, in a wholly analogous position, played …Ne4 and likewise obtained an advantage thereby. Of course, Réti’s quieter development is also quite good.

9… Ne4

If the liberating move of 9… e5 , recommended by Rubinstein and others, is really the best here – then it furnishes the most striking proof that Black’s entire arrangement of his game was faulty. For the simple continuation 10. cxd5 cxd5 11. dxe5 Nxe5 12. Nxe5 Bxe5 13. Bxe5 Rxe5 14. Nc4 Re8 15. Ne3 Be6 16. Qd4 , would have given White a direct attack against the isolated Queen’s pawn, without permitting the opponent any chances whatsoever. Moreover, the move selected by Bogoljubow leads eventually to a double exchange of Knights, without moving the principal disadvantage of his position.

10.Nxe4 dxe4 11. Ne5 f5

Obviously forced.

12.f3

The proper strategy. After Black has weakened his position in the centre, White forthwith must aim to change the closed game into an open one in order to make as much as possible out of that weakness.

12… exf3 13. Bxf3

Not 13. exf3 , because the e-pawn must be utilized as a battering ram.

13…Qc7

Also after 13… Nxe5 14. dxe5 Bc5+ 15. Kg2 Bd7 (after the exchange of Queens, this Bishop could not get out at all) 16. e4 , White would have retained a decisive advantage in position.

14.Nxd7 Bxd7 15. e4 e5

Otherwise would follow 16. e5 , to be followed by a break by means of d5 or g4. After the text move, however, Black appears to have surmounted the greater part of his early difficulty and it calls for exceptionally fine play on the part of White in order to make the hidden advantages of his position count so rapidly and convincingly.

16.c5 Bf8 17. Qc2

Attacking simultaneously both of Black’s centre pawns.

17… exd4

Black’s sphere of action is circumscribed; for instance, 17… fxe4 clearly would not do on account of the two-fold threat against h7 and e5, after 18. Bxe4 18. exf5 Rad8 . After 18… Re5 19. Qc4+ Kh8 20. f6 , among other lines, would be very strong.

19.Bh5

The initial move in an exactly calculated, decisive manoeuvre, the end of which will worthily crown White’s model play.

19… Re5 20. Bxd4 Rxf5

If 20… Rd5 21. Qc4 Kh8 22. Bg4 , with a pawn plus and a superior position.

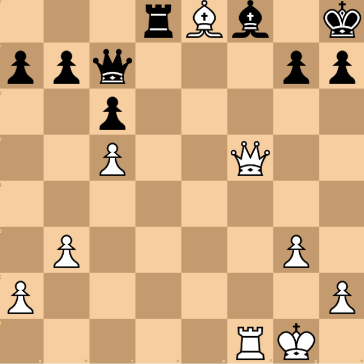

21.Rxf5 Bxf5 22. Qxf5 Rxd4 23. Rf1 Rd8

Or 23… Qe7 24. Bf7+ Kh8 25. Bd5 Qf6 26. Qc8 , etc. Black is left without any defence.

24.Bf7+ Kh8 25. Be8

A sparkling conclusion! Black resigned, for, after 25… Bxc5+, he loses at least the Bishop. Rightfully, this game was awarded the first brilliancy prize. 1-0

Ray’s 206th book, “ Chess in the Year of the King ”, written in collaboration with Adam Black, and his 207th, “ Napoleon and Goethe: The Touchstone of Genius ” (which discusses their relationship with chess) are available from Amazon and Blackwells.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.