Populist nationalists and liberal internationalists now dominate British politics

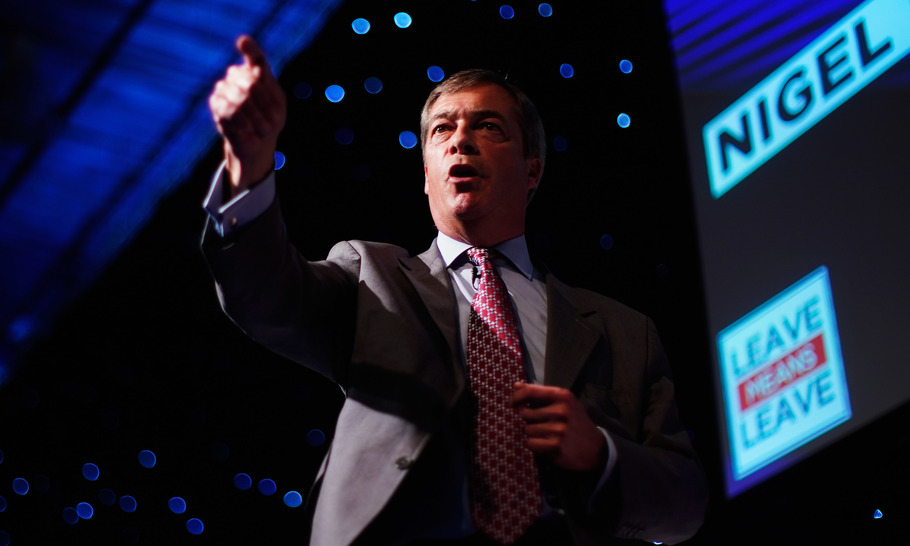

Photo by Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

Nigel Farage’s new party has now eclipsed both Labour and the Conservatives in opinion polls ahead of the European elections. Two YouGov polls this week, most recently for The Times, put the insurgent Brexit Party in the lead with just over a month to go.

It is hard to predict whether the surge in support for Farage’s hardline party will endure until May 23, when the European parliamentary elections are due to take place unless Parliament has already ratified the Withdrawal Agreement. Polling figures for all the parties are still volatile, reflecting publicity on social media as well as frustration on both sides of the Brexit divide.

Most of those who voted for Ukip when it was led by Farage in 2014 — when it became the largest British party in the last EU elections with almost 27 per cent — appear to have transferred their support to his new party. Ukip has been relegated to fringe party status since its leader, Gerard Batten, decided to embrace Tommy Robinson’s brand of street politics and conspiracy theories.

On the other side of the spectrum, Jeremy Corbyn will now be under renewed pressure to endorse a second referendum. Polling evidence suggests that Labour support might improve from its present level of 22 per cent if the party were to win back Remainers from another new party, Change UK, led by former Labour and Tory MPs.

Yet Labour could not hope to retain many of the constituencies which voted Leave if the party were to adopt the unambiguously Remain stance taken by the majority of the parliamentary party. The Brexit Party appeals to working-class Labour voters no less than to middle-class Conservatives.

For the Tory party, the only chance of avoiding an embarrassing defeat is to leave the EU before the poll could take place, as Jeremy Hunt, the Foreign Secretary, said earlier this week. That attitude, however, implies that the party’s interest is being given priority over the national one. It seems unlikely, moreover, that a Government that has hitherto failed to get its Brexit deal through the Commons on three occasions will suddenly persuade its dissident MPs and DUP allies to abandon their objections.

Despite their low turnout in this country, the EU elections always matter and, assuming that these ones do take place, will matter even more this time. If Farage re-emerges as the arbiter of British politics — the role he played briefly when he forced David Cameron to promise a referendum in the 2015 general election — then Theresa May’s position will become even more precarious. The Prime Minister is now irrevocably identified with delaying Brexit until at least October 31, and these elections will be seen as a referendum on her handling of the negotiations.

Meanwhile in Brussels a deep divide has emerged between those who now want Britain to leave as soon as possible and those who still hope that Brexit can be postponed indefinitely. A victory for the Brexit Party would inevitably favour the former faction, and it was no surprise to see Farage warmly applauding Guy Verhofstadt in the European Parliament when the latter warned that Britain’s participation would “poison” the elections and “import the Brexit mess into the EU”.

Donald Tusk, the EU Council President and architect of the extension plan, was sharply critical of Verhofstadt’s view, reminding him that the UK was still an EU member state. Tusk rejects the French idea of reducing the British to a lower “intermediate” status: “I cannot accept a second category of membership.”

What seems clear amid the speculation is that Brexit will continue to dominate the agenda, not only here but on the Continent too. The irony is that, on the verge of leaving the EU, the map of British politics increasingly resembles that of most other European countries, which are divided between liberal internationalists and populist nationalists. Just as Britain turns its back on Europe, our politics seems ever more European.