Roll on, Roulin: Van Gogh in Boston

Portrait of Madame Augustine Roulin (1888) by Vincent van Gogh

The lively and innovative exhibition of Van Gogh: The Roulin Family Portraits continues in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston until September 7, 2025. Van Gogh painted 26 portraits of the Roulin family, his working-class neighbours in Arles, from July 1888 to March 1889.

During that time he was in and out of insane asylums, and suffered bouts of severe illness, madness and self-mutilation, shortly before his suicide in 1890. The postman Joseph Roulin wrote to Vincent’s brother Theo on December 26, 1888: “I am sorry to tell you that I think he is lost. Not only is his mind affected, but he is very weak and disconsolate.” Two days later he added: “Vincent had a terrible crisis; he had a very bad night, and they had to put him in an isolated room. He has not eaten a thing since being confined in that room and has withdrawn into total silence.”

In these portraits Van Gogh used thick visible brushstrokes and highly charged colours that were not truthful or realistic, but suggested his extreme emotions and ardent temperament. His personal friendship with the family closed the usual formal distance between the artist and his subject. He painted with astonishing speed, some rough pictures were “knocked off in one hour,” and completed all five Roulins in one week. Original photographs of the Roulins reveal that his portraits were not exact images of the subjects, but expressionistic versions of how Van Gogh saw them. He aimed for a different and deeper resemblance, and declared, “I’d like to find an individual likeness, of the whole man, his mood, his character, his essential self, in flesh and blood.” The sitters, though pleased to receive their portraits as payment for modelling, must have wondered how they had inspired such weird works.

The portraits of the Roulins represent the family from adults to baby. They include the postman Joseph aged 47, his wife Augustine aged 37, their older son Armand aged 17—a blacksmith’s apprentice “who has been striking the iron hard” — their younger son Camille aged 11 and their newborn baby Marcelle. Van Gogh’s copies of these portraits, like musical variations on a theme, allowed him to paint without a model, to improve previous work and to distribute copies. Three versions of the same portrait were divided: one given to the Roulin family, one to his art dealer brother Theo to exhibit or sell in Paris, and one to keep himself.

Joseph Roulin, 12 years older than Van Gogh, was his best friend and drinking companion in the Café de la Gare near Van Gogh’s Yellow House in Arles. He not only delivered letters, but also “worked as brigadier-chargeur, responsible for loading and unloading the mail transported by train.” Vincent wrote enthusiastically to Theo: “Roulin lives a great deal in cafés and is certainly more or less a drinker and has been so all his life. But he’s so much the opposite of stupefied, and his elation is so natural, so intelligent, and he argues with such a broad sweep. . . . While Roulin isn’t exactly old enough to be like a father to me, all the same he has silent solemnities and tendernesses for me . . . such a good soul and so wise and so moved and so full of belief.”

This catalogue (with ten contributors and 232 pages for the modest price of $35) emphasises the biographical background of the paintings, but does not carefully describe them. In Postman Joseph Roulin this dignified masculine figure, seen close-up and staring straight out at the spectator, rests one arm on the chair, the other on the edge of the green table. Seated against a blank, pale blue background, he has a fringe of hair, thick raised eyebrows, widely spaced blue eyes with red lids, ruddy complexion, pointed ears, broad nose, full lips and shaggy beard streaked with yellow, which looks like a wheat field and descends to his chest. He presents a stiff military posture, wears a dark blue peaked cap with his profession “Postes” displayed in gold letters in a band above his brow, and a naval-type, double-breasted uniform with two rows of four brass buttons and curvy yellow braid on his sleeves. A V-shape appears in the fork of his beard, in the top and bottom folds of his jacket, between his open legs and his curved fingers tensely spread as if ready for action. Van Gogh paid for the modeling with food and drink when Roulin’s wife was away, which cost a lot to satisfy his hearty appetite, and later gave him copies of the portraits.

Vincent van Gogh – Portret van de postbode Joseph Roulin

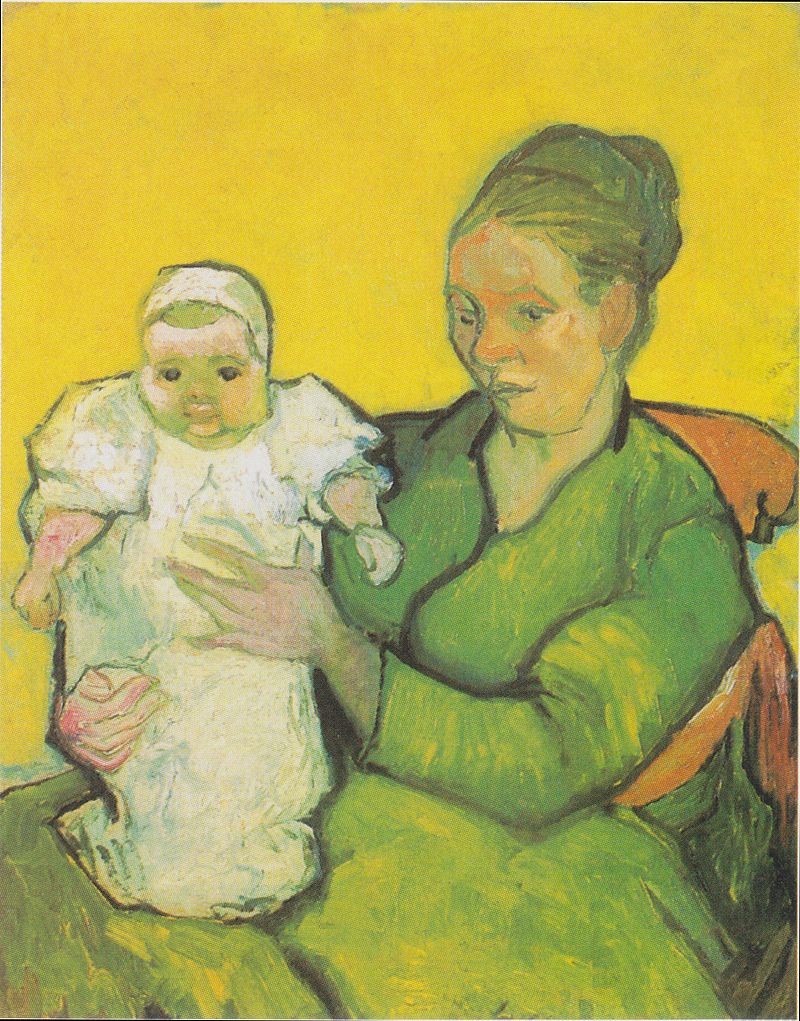

Van Gogh described Augustine, La Berceuse (“the cradle rocker”), as “a woman dressed in green. Her hair is entirely orange and in plaits. The complexion worked up in chrome yellow. The hands hold the cradle cord. The wallpaper is blue-green with pink dahlias and dotted with orange and with ultramarine.” The bulky, thick-armed, big-breasted, wide-hipped maternal figure sits snugly into a round brown chair with his signature “Vincent ’89” on the arm. She’s placed in front of a dotted green background decorated with 16 white flowers. She has a calm, hieratic expression and folds her worker’s hands over the rope that sways the cradle.

Lullaby – Madame Augustine Roulin Rocking a Cradle

The handsome chest-length figure in Armand Roulin has a pale green background. He wears a slanted dark blue, wide-brimmed hat, and has green eyes, broad nose, wavy lips and thin moustache. His yellow jacket is buttoned at the top over a blue waistcoat and open-necked white shirt. The colours from green and blue to white and yellow are clearly defined and sharply contrasted. His expression is manly, swaggering and self-confident.

Portrait of Armand Roulin

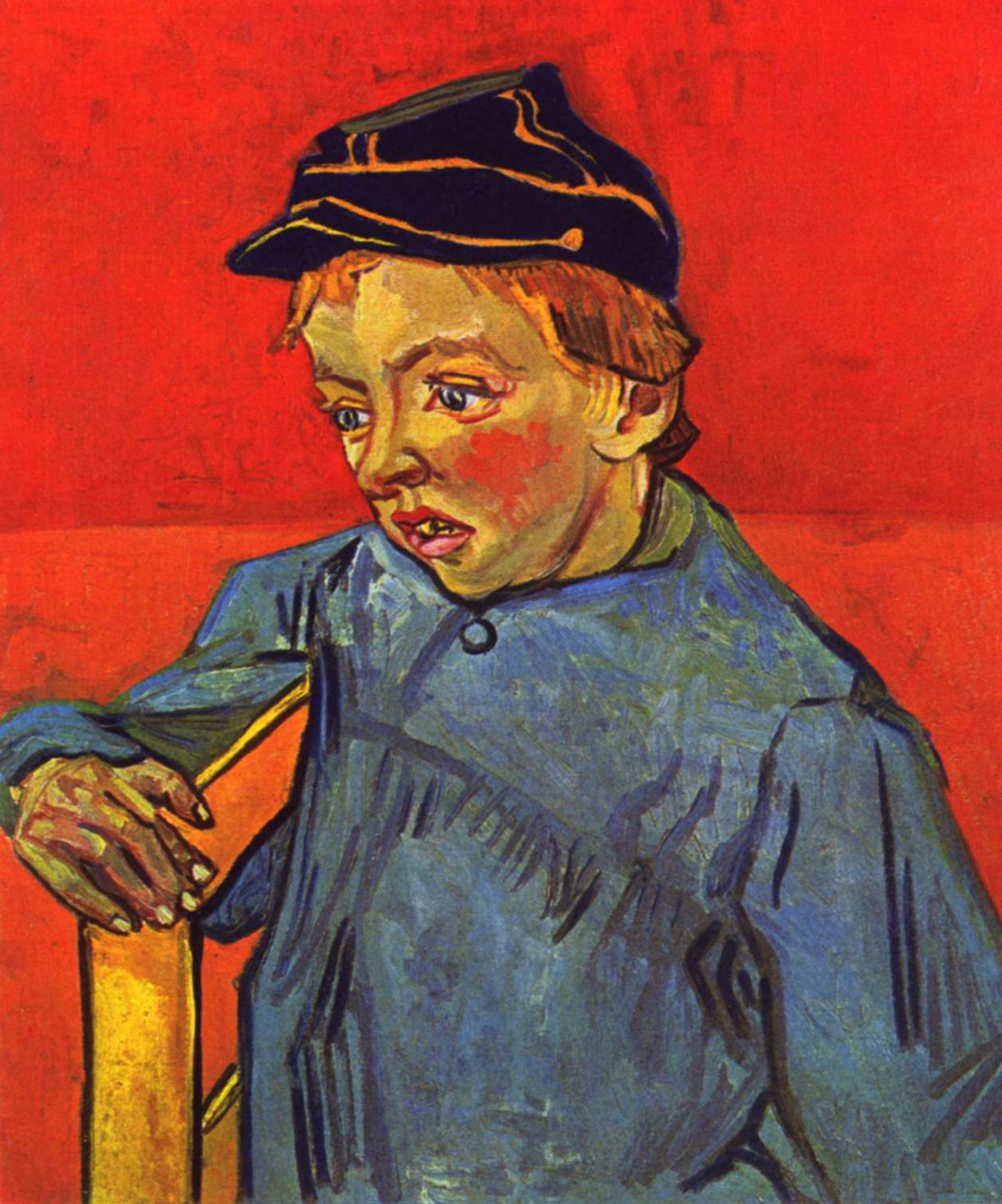

In The Schoolboy “Camille is dressed in his school uniform with a blue, high-buttoned jacket and dark-blue cap with golden-yellow accents.” He’s seen in 3/4-view, gripping the right arm of the chair with claw-like fingers. His blue cap echoes his father’s. His blond hair drops down to his left ear, his eyes and nose are large, his cheeks ruddy. His mouth, revealing irregular teeth, hangs open as if he had been startled by the intense and sometimes manic artist.

Vincent van Gogh: The Schoolboy

The well-fed baby daughter in Marcelle Roulin has bulbous, drooping, pink, hog-cheeks and chin. Filling the frame, dressed in white cap and gown, with large blue eyes, wide nostrils and a huge lopsided face, she has a gold bracelet on one wrist and clasps her hands on her ample belly. Van Gogh’s brushstrokes convey the plump essence of babyness.

Van Gogh – Marcelle Roulin als Baby2

In the catalogue the thesis-driven chapter on “Van Gogh, Rembrandt and Frans Hals” yokes the artist by violence together with two great 17th-century Dutch painters. Sprinkled with “one can imagine” and “perhaps thought,” this chapter is not convincing. Carel Fabritius, who died at the age of 32, did not leave “an incredibly small oeuvre.” It would be “incredible” if he’d left a large oeuvre. Van Gogh did not need the inspiration of Hals and Rembrandt “to look at people he encountered on the streets.” He did not need a precedent and validation of their pictures in the Louvre to paint the Roulins. He did not “assimilate bold strokes” from Hals. It’s not at all “amazing” that “the Postman and Hals’ The Merry Drinker “are almost the exact same size.” This scholar also states the obvious and banal: “The power of Rembrandt’s portraits comes from the presence of the individual sitter.”

Frans Hals and Van Gogh’s “young child balanced on the lap of a female are not “closely related compositions.” Thousands of other paintings, beginning with the Virgin and Child, have the same traditional composition. The comparison of Rembrandt’s Aeltje Uylenburgh and Augustine Roulin is also farfetched. The 17th-century works are faithful portraits of elaborately costumed patrons, who paid for this work and wanted to be immortalised. By contrast, Van Gogh’s portraits are intensely personal and idiosyncratic responses to his models. Anyone who is not blind is immediately struck by the differences, not the similarities.

Van Gogh – Madame Augustine Roulin mit Baby

One quarter of the catalogue is taken up by highly specialised technical studies that would interest very few spectators or readers. The authors falsely claim, “Through this close looking at the support, paint layers, and surface coatings of the Postman and La Berceuse, we came to a much more sophisticated understanding of Van Gogh’s working methods and materials. . . . The application of the paint in the background is particularly intriguing.” In fact, it isn’t the slightest bit intriguing. They awkwardly and anti-climactically conclude: “Inspection of the paint surface under the stereo-microscope, combined with the observation of its characteristic fluorescence induced by ultraviolet illumination, suggests, however, that Van Gogh used eosin.” Wow!

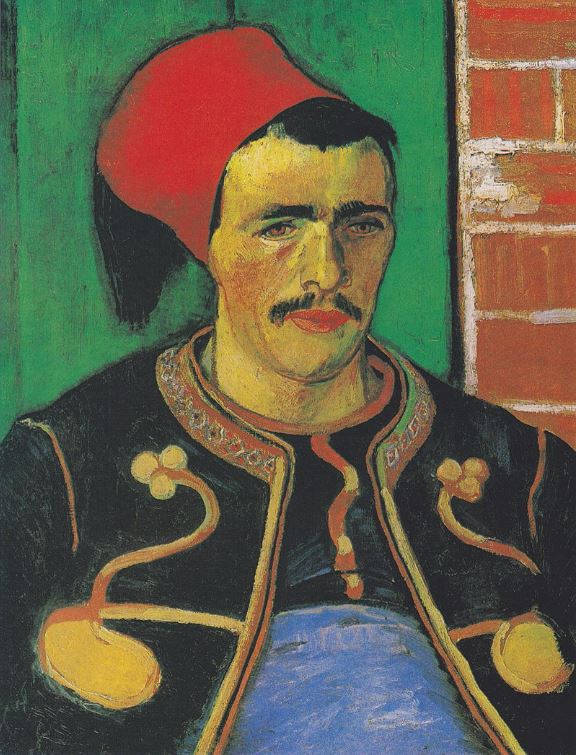

Van Gogh painted five important works on other subjects in Arles. In The Zouave the soldier stands before a green door and orange-brick wall, faces the spectator and wears the exotic uniform of a light infantry regiment in North Africa. His tasseled red fez is tilted off his head, the collar and chest of his jacket and vest are elaborately decorated, and a wide blue sash sweeps across his belly. The handsome virile man has black hair, deep-set eyes, sloping dark mustache and full red lips. He seems ready to report for duty in the next battle.

Van Gogh – Der Zuave (Halbfigur)

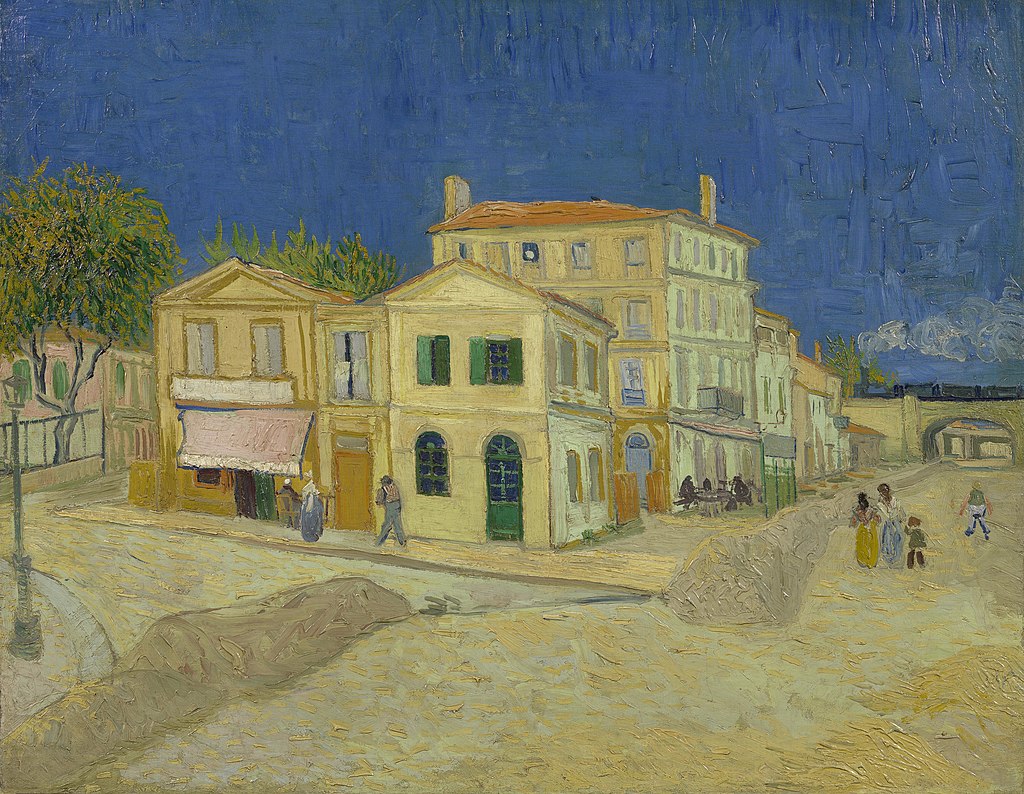

The Yellow House portrays the residence in Arles that Van Gogh shared miserably with Gauguin in 1888. It’s placed between a heavy blue sky and two wide yellow streets, with a few trees and tiny pedestrians. In the background a railway bridge supports a long black train that trails clouds of smoke. The house has two stories, green shutters and a high, oval, glass-panel front door. It stands in a lamppost-lit square, and in front of a four-story building with a red tile roof and café with a pink awning and a few dark-clothed drinkers. The apparently tranquil appearance of the Yellow House hides the turbulent life that Van Gogh led inside.

Vincent van Gogh – The yellow house (‘The street’)

The tilted, colorful Bedroom in Arles has a green-and-rose tiled floor, with five portraits and landscapes angled off the pale blue walls. There’s a tawny-colored pinewood bed, high at both ends, with two crumpled white pillows and a puffed bright red duvet. The room is austerely furnished with a clothes rack supporting jackets and straw hat, two low straw-bottomed chairs, a small square table loaded with pitcher, basin, carafe and bottles, a long hanging grey towel, a green-framed half-open window with eight panes showing a blurry green and yellow scene outside, and a mirror that reflected Van Gogh’s face in his self-portraits. Two firmly closed blue doors on either side of the room give a claustrophobic feeling.

Bedroom in Arles (first version, 1888).

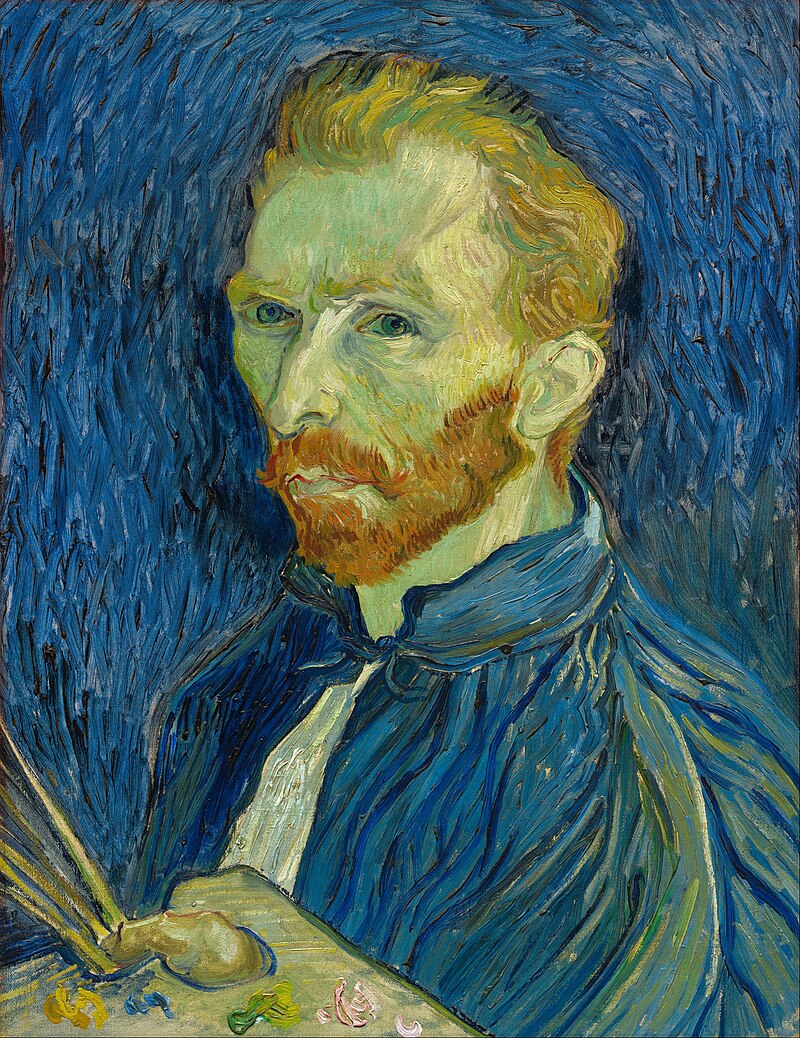

In the Self Portrait of 1888 Van Gogh looks like an escaped convict or madman, stripped down to his bare essentials. He has a broad forehead, pale furrowed skin, deep-set, widely-spaced, staring blue eyes, sharp high-ridged nose, closely trimmed beard, dark brown jacket and waistcoat. His grim expression suggests that he’s heading for chaos and disaster. In the idealised Self-Portrait, completed a year later, he looks quite handsome and back in control of his life. He stands half-length in 3/4-view in front of a swirling dark blue background that’s reprised in his high collared blue jacket tied loosely over a white shirt. His red hair is blown back above his wide pale yellow forehead, his mustache curls into his beard, his eyes are deep blue and his nose strong. His bent thumb holds a paint-streaked palette and five brushes in his left hand, and he seems determined to plunge into his work with newfound energy and high seriousness.

Self-Portrait, August 1889

Jeffrey Meyers, FRSL, has published Painting and the Novel, Impressionist Quartet, biographies of Wyndham Lewis and Modigliani, and a book on the Canadian realist painter Alex Colville.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.