Sturgeon and the SNP should be careful what they wish for

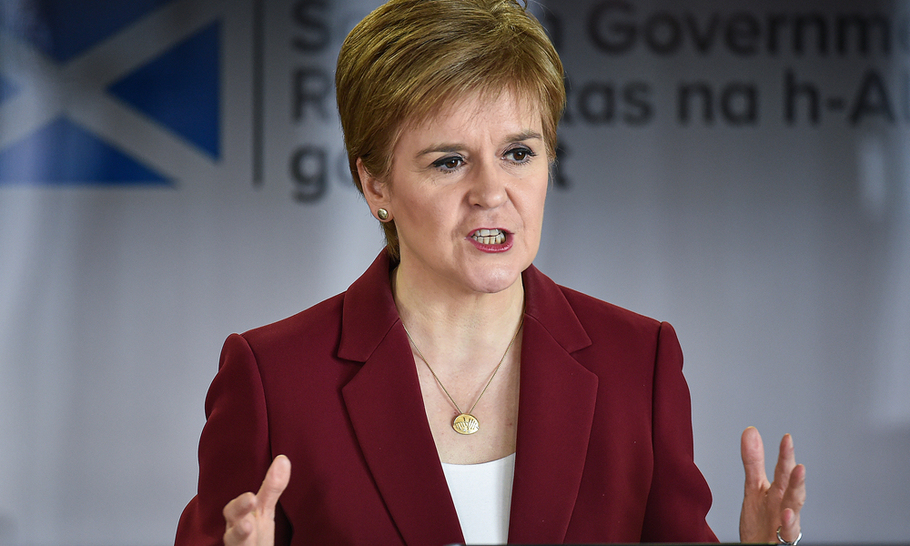

Nicola Sturgeon, January 2020 (Shutterstock)

Has Nicola Sturgeon made her first mistake? Looking drawn, tired, and badly in need of a winter break, the Scottish First Minister chose an interview with Andrew Marr to announce that the next Nationalist government of Scotland would hold what she called an “advisory referendum”.

A Sunday Times poll which generated much media excitement last week actually showed minority support for Scottish secession – 49 per cent. It is only by adding in undecided voters that the SNP’s preferred 52 per cent figure is reached.

Polls in favour of Scottish secession started to move to 50 per cent not long after Boris Johnson won his election. A combination of his insisting on a hard Brexit and threatening a no-deal rupture with Europe, when Scots had voted 2-1 to stay in the EU, and his maladroit handling of the pandemic, have pushed more Scots (and, to a lesser extent, Northern Irish and Welsh people) to express their displeasure by telling pollsters they wanted their own government.

There is nothing new in this. At the beginning of the last century the great reforming Liberal government of 1906 was full of talk about a parliament and home rule for Scotland. A Bill was even introduced in the Commons for a Scottish Parliament. The federal system of rule in Canada, Australia and the United States was seen as a better model than the unified, central, all-power-to-WW (Westminster and Whitehall) model of Conservative Britain.

In 1912, Winston Churchill called for “a federal system in the United Kingdom, in which Scotland, Ireland and Wales, and, if necessary, parts of England, could have separate legislative and parliamentary institutions, enabling them to develop, in their own way, their own life according to their own ideas and needs.”

Today, Gordon Brown of course dare not use the term “federal” — which since Brexit has been banished from the UK political lexicon — but the ideas he and Sir Keir Starmer are advancing are little different from Churchill’s a century ago.

On the BBC Today programme, Brown lamented the lack of consultation between Boris Johnson and the leaders of the UK’s devolved administrations or the big city mayors. A cynic might ask how often, as Prime Minister, Brown himself invited Alex Salmond as First Minister of Scotland after 2007 or Boris Johnson as Mayor of London after 2008 in to 10 Downing Street to take their advice and give them support.

There is a gap wider than the Moray Firth, however, between Brown’s ideas of more devolution and power for Scotland and the other nations and regions and Nicola Sturgeon’s populist demand for full nationalist secession. But she may be taking a big risk in taking the Catalan option of a referendum as a stand-alone nationalist secessionist project even if she dubs it “advisory”.

Though only 50, Ms Sturgeon gives the impression of being a politician in too much of a hurry. The lamentable record of the SNP in government on education, health, and economic development has been obscured by making independence the only political story north of the border. The once-strong Labour, Tory and Liberal parties in Scotland have all but disappeared, without any leaders who command presence or enthusiasm.

Gordon Brown is by far the biggest political beast in Scotland. But at 69, a decade younger than Joe Biden, he appears unwilling to get down and dirty and take on the nationalist populism of the SNP.

The Scottish Tories are lost as their MPs — unlike their MSPs, such as the former leader Ruth Davidson — were all keen to bust the union with Europe. The party leadership ignored overwhelming support in Scotland to be allowed to do business with or travel and settle in Europe if they so desired.

But even the most ardent of secessionists in the SNP know that a one-party statelet in Scotland, which will be confirmed in the Holyrood parliamentary election later this year, soon loses inner coherence and stability. The noises from within the SNP and the grave accusations against Ms Sturgeon over her campaign against her predecessor and mentor, Alex Salmond, are not those of happy successful politics.

Hence her new proclamation about holding a referendum. The problem is that it will not be approved by the House of Commons. Other than the SNP itself, a handful of Welsh nationalist MPs and the Greens’ Caroline Lucas, it will not get support in Westminster.

So any referendum would be held against the agreed legal and constitutional arrangements in the UK. To change them, the SNP needs to win a massive majority of MPs from Scotland in a general election to the House of Commons, as Sinn Fein did in 1918. That made Irish secession unstoppable and panicked Westminster into the partition of Ireland – the “Protestant parliament for a Protestant state”, as the Ulster unionist leader Sir James Craig put it.

A 49 per cent poll for independence in the Sunday Times and a majority of SNP MSPs from a low turn-out Holyrood poll is not the overwhelming, unstoppable moment to break up the Union of Scotland and England that Ms Sturgeon imagines.

The provocation of holding a party political, populist national referendum will not find favour in Europe — even if most EU leaders assume the decision of Boris Johnson and Tory MPs to turn Brexit into a project of southern English supremacism will sooner or later fall apart, as his version of Brexit turns out to be unworkable.

Josep Borrell — a Catalan Socialist, utterly opposed to Catalan secession — was foreign minister of Spain before going to Brussels in 2019 to be the EU’s High Representative for foreign policy. As Spanish foreign minister, he said Madrid, and by extension the rest of Europe, would accept Scotland leaving the UK — provided it was done legally and constitutionally. “If they leave Britain within the accordance of internal regulations, if Westminster agrees, we are not going to be more Catholic than the Pope,” he said in 2018.

As Sir Julian King, the British Ambassador in Paris under David Cameron and then the last UK Commissioner in Brussels, points out, the SNP makes much of having the EU as an alternative to the UK, a new union to replace the one destroyed by the vote of English but not Scottish citizens in 2016.

But Europe acted with horror at the adventurism of Catalan nationalist secessionists, organising their own private referendum in October 2017 on the authority of a vote in the Catalan Parliament but not the Cortes of all Spain.

MPs should ignore the nationalist populist stunt of the SNP in holding a plebiscite which they cannot lose. Non-SNP parties in Scotland should urge voters to abstain.

Up to now the SNP has shown strategic patience. Hitherto the SNP always underlined that its demand for secession would be done legally and constitutionally. There is a dramatic change in that policy, as Nicola Sturgeon for internal party reasons wants to hurry history along. But she and her party should be careful what they wish for.

Meanwhile Boris Johnson could quickly kill Scottish secession by rethinking Brexit: not to reverse the 2016 referendum, but to re-interpret it along Swiss or Norwegian lines. This would allow Scotland and Scots to restore their centuries-old alliance with Europe and would deflate the SNP’s main claim for support. On the issue of Scottish separatism, the interests of the EU and the UK are perfectly aligned.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout the pandemic. So please, make a donation.