Tax rises serve no practical purpose

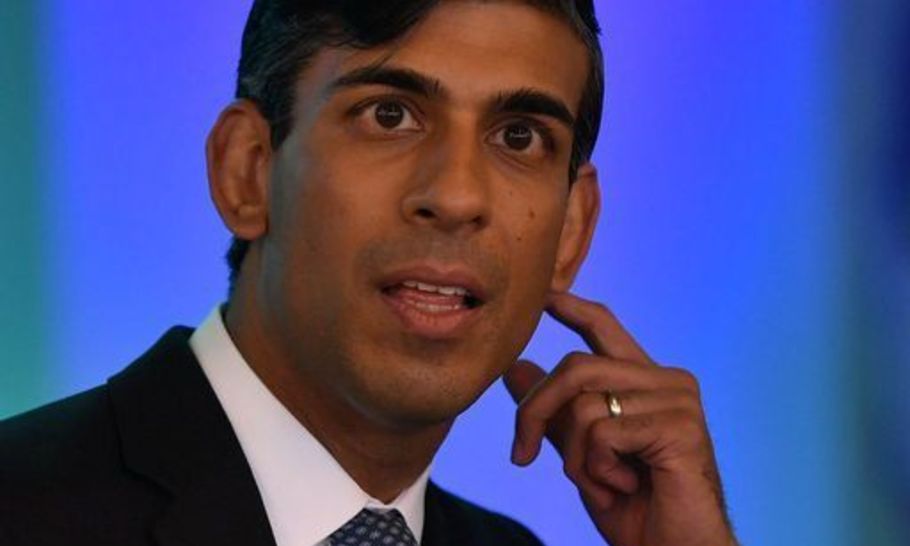

Daniel Leal-Olivas/PA Wire/PA Images

We live in turbulent times. On July 8th Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, delivered to Parliament what he officially called “A Plan for Jobs 2020” and was generally dubbed in the media a “mini-Budget” or an “emergency Budget.” It included some tax cuts as part of an effort to recharge the economy. But in the full Budget, due in November, officials from the Treasury have been busy briefing the media that there will be significant tax increases.

Last weekend, the Sunday Times suggested that an increase in Corporation Tax from 19 per cent to 24 per cent is being proposed which “would raise £12 billion next year.” In the last financial year, the revenue from Corporation Tax was £52 billion. So that estimate (whether the journalists came up with it or they were briefed it by some Treasury deepthroat) assumes no behavioural change at all. That is absurd. In this swashbuckling era of globalisation tax rates can prompt rather substantial changes in behaviour.

Indeed when George Osborne was Chancellor of the Exchequer he used to cut the Corporation Tax rate in his annual Budget and then see the revenue generated increase in the following year. Each year when he announced a cut the pundits would state, quite emphatically that it would mean a loss to the public coffers. There howls of dismay as the Government “giving away money” to rich businessmen. Yet those who scrolled down the public accounts (admittedly an unexciting pursuit) could see that more money was being taken from them.

Other changes from Osborne were less satisfactory. In 2014, Stamp Duty on the taxes on the most expensive properties rose from 7 per cent to 12 per cent. Then he put on another three per cent additional charge. Had the number of transactions remained the same then that would have raised a lot of extra money. But instead, the market for those homes, usually in London, froze and the proceeds to the Treasury fell.

Of course, we can’t know for sure what would have happened if these tax changes hadn’t been made. But Mark Littlewood, of the Institute of Economic Affairs, offers this general guide: “The economic literature suggests that if all you care about is increasing GDP growth, you probably want state spending to be about 20 per cent of national income. If you want to maximise welfare — not simply growth rates — this rises to approximately 30 per cent. If you want merely to maximise state spending, but want it to be sustainable over the long term, you probably can go as high as 38 per cent. In the UK this year, government spending is likely to be about 45 per cent of GDP.”

The signs are that we are currently seeing a repeat of this lesson with the revival of the housing market. In July, Sunak announced that the nil rate Stamp Duty band would increase from £125,000 to £500,000. The Treasury said this would mean they would miss out on £3.8 billion. That was based on the assumption that there would be the same volume of sales as we had in 2019/20 when £11.6 billion was brought in.

But then coronavirus brought home just how volatile the property market can be. From April to June this year proceeds were 43 per cent down on the same period last year. It is fair to say that the current quarter would have bobbed up anyway with the lockdown being gradually eased. The point is that the Stamp Duty cut has greatly boosted that recovery. Zoopla has said that properties are selling 31 per cent faster than last year, with the average time taken to sell falling from 39 days to just 27.

John Redwood, the Conservative MP, says: “The cut in Stamp duty has encouraged people to get on with swapping their home to a property that is closer to their current needs. It has helped people downsize and upsize, to move from urban areas to more rural areas, or to move into cities from the countryside. It has allowed people to buy extra space for home-working, or locate closer to schools or workplaces. It has given them more choice. As a result housing transactions have just exceeded the pre-pandemic levels. When people move it creates work for the estate agents, conveyancers, mortgage businesses, removal firms, painters and decorators, builders doing small works and many others.”

So if the Chancellor is wise he will decide to make the temporary Stamp Duty cut permanent. If he does then I predict he will bring in more money from it next year than was raised last year.

Even if the sole objective of Government policy was to be able to fund the maximum level of public spending then further tax rises do not make sense. One would hope that for a Conservative Government the mission would, in any case, be rather different. There should be some recognition of the importance of individual choice when it comes to spending our own money — rather than having those choices taken from us and exercised by the state.

Yet whatever the political hue of the Government, we have reached the end of the road when it comes to tax rises serving any practical purpose. The only motive for them could be to seek short term popularity by appealing to envy with an attack on the rich. When it comes to restoring the public finances to a sustainable footing the optimistic course would be to rely on growth, the more pessimistic one being spending cuts. A bit of both could be realistic.

What is dishonest is to proclaim being “responsible” on putting up tax while ignoring the danger that such action would cause debt to rise even further.

As with all economic forecasts we are in the territory, as we would say on a jury, of the “balance of probabilities” rather than “beyond reasonable doubt”. With the impact of any tax change, we can never prove the counterfactual. What would have happened if the change had not been made? But the probability that a substantial tax rise would be highly detrimental to the economic recovery is strong. That would not be a prudent course for the Chancellor to take.