Time travel for the brain

(Photo by Art Media/Print Collector/Getty Images)

A type of quiz becoming popular on chess websites is based on the concept of degrees of separation. In the case of chess, the conditions revolve around how quickly one can link via one’s own opponents to a legendary figure of the past, or even to a possible win against a world champion. A typical example, recently launched on the well regarded ChessBase website, is headed WinChain and actually offers an app which helps trace your links, via your own opponents, to a potential concatenation of encounters culminating in a game, or even a victory, against a chess board Titan.

For example, I have defeated the Red Czar of Soviet Chess, Mikhail Botvinnik, which gives me a ChessBase WinChain score of 1 against a world champion. I have also twice drawn against Max Euwe, the Dutch Grandmaster, who held the world title from 1935-1937. Euwe, like Botvinnik, played against World Champion Emanuel Lasker (champion from 1894-1921) who in turn had met the English Veteran Henry Bird across the board, as early as 1890. Bird himself encountered Staunton, Morphy and Steinitz, to name but a few.

Hence, with just four degrees of chessboard separation, I already connect to the golden era of British chess.

In the 1840’s London was the epicentre of world chess. Simpson’s-in-the-Strand was the universally acknowledged headquarters of the civilised chess world, and Howard Staunton, with his decisive match victories against European champions, such as St. Amant, Horwitz and Harrwitz, was widely recognised as the wielder of the sceptre, formerly gripped by the Frenchmen: De La Bourdonnais, Deschappelles and Philidor. Yet Staunton was not the sole English talent of the day, which included the aforementioned Bird, Buckle, Williams and Barnes, the last of whom succeeded in taking one game off the otherwise invincible Morphy, amazingly, with the stunningly irregular, indeed outrageous, opening defence for Black: 1e4 f6. This might be seen as a curious prequel to the game which a later British chess superstar, Tony Miles, won against World Champion Anatoly Karpov, using the bizarre defence 1e4 a6.

It is interesting to observe, in the intellectual fields of both science and chess, that the global capital shifted from Paris to London, as Staunton succeeded his Gallic colleagues over the chessboard, whilst also defeating the other leading Europeans, just as Richard Owen and Charles Darwin began to supplant Lamarck and Cuvier as the chief palaeontologists and theorists of evolution.

Although Staunton could no longer claim to be champion beyond 1851, his reputation acted as a sufficiently powerful magnet to attract to London such powerful protagonists of the game as Horwitz and Harrwitz, both Staunton victims, as noted above, not to mention Lowenthal, Morphy, Anderssen, Zukertort, Steinitz and ultimately Lasker.

If I could travel back in time, physically, not just mentally, I would undoubtedly return to that Victorian era, when the giants of world chess congregated regularly at Simpson’s, where Sir Arthur Conan Doyle also placed Sherlock Holmes “for something nutritious” after the solution of two of his most trying cases.

This was an epoch when top hats could be worn during games, when the smoking of cigars was still permitted whilst pondering one’s moves and roast joints and fine claret could be served at the table, while chessboard combat continued. I fondly imagine that I would have blended in quite comfortably.

In terms of world champions played, I can list Euwe, as previously noted, Botvinnik the first Soviet World Champion, Smyslov, Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Karpov. I have also played against the duo of Garry Kasparov and Nigel Short, in a consultation team for television, where our side also included Jon Speelman, Daniel King and Cathy Forbes.

The glaring omission from my list of champions is Bobby Fischer. This is surprising, since, to a great extent, our careers coincided. For example, I was reigning British Chess Champion when Fischer won the World Title in 1972. Fischer, however, became a distinctly rara avis in the chess menagerie, especially after he won the World Championship, and, in common with the Loch Ness Monster, he was often sighted, but never actually seen. Although our paths often crossed, I never had the opportunity to play against him.

Indeed, few living British players have encountered Fischer across the board. Ten times British Champion, Jonathan Penrose, has pulled off this feat, as has my co-team member in the TV game, three times British Women’s Champion, Cathy Forbes, who may be the only living British chess player to have played against Tal, Fischer and Kasparov. Cathy also crossed mental swords with Kasparov in 1984, as part of the very first satellite chess display, which I organised between teams of young players facing Kasparov from London and New York. At that time, such instantaneous distance combat was nothing short of revolutionary. Now it is the norm, with an entire chess Olympiad, or global championship for national teams, being contested online as I write.

Here are Cathy Forbes’ games against Garry Kasparov in 1984 as Black, against Bobby Fischer in 1992 as White, and against Tal as Black in a five-minute game. A remarkable coincidence is that Cathy lost against Tal and Kasparov after being blown away in both cases by a spectacular queen sacrifice.

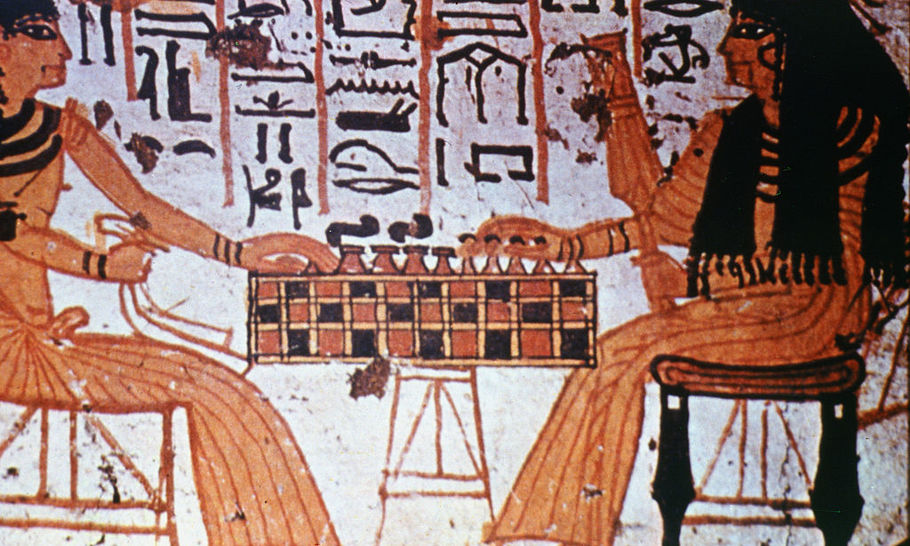

In an earlier column I mentioned that one famous time traveller, Dr. Who, in the Tom Baker incarnation, regularly lost at chess against his faithful robotic dog, K9. In a very real sense time travel is possible in chess, given that more or less every significant game ever played has survived intact. Since the days of the sublime Philidor, at the very least the moves exist, so it is possible to relive a contest from the days before electronic recording of sporting events was technically available.

In the most felicitous instances, the comments from the time the game was played also survive, while, failing that, modern computer analysis can still penetrate to the truth of the key variations and thus analyse the moves which matter. In most other competitive events this cannot be done, whereas the existence of chess moves permits us to experience the game as it happened, not just a commentator’s description of the game.

I conclude this week with a trip back in time to 1788 and a thrilling game between two illustrious opponents. These were the infamous Thomas Bowdler, who rewrote and sanitised all the plays of William Shakespeare, as well as Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire; his opponent being Field Marshal Henry Seymour Conway. Conway was a celebrated soldier who had fought against Bonnie Prince Charlie at the Battle of Culloden in 1746.

Dr. Thomas Bowdler, 1754-1825, was that prudish, yet self confident, man of letters who doubted that Shakespeare could be served up uncensored for the tender sensibilities of women and children. For this reason he expurgated the Bard’s original texts — or “Bowdlerised” them — thus introducing a new word into the English language. Bowdler’s Family Shakespeare notoriously and in his own phrase, “omitted those words and expressions which cannot with propriety be read aloud in a family.”

Less well publicised were Bowdler’s efforts on the chessboard. An enthusiastic and imaginative player, during the late 1780s and early 1790s, Bowdler was a contemporary of the great French master Philidor who had found refuge in London from the ravages of the French Revolution. The Bowdler victory against Conway, (as given above) has the distinction of being a role model for The Immortal Game between Anderssen and Kieseritski, played over half a century later… at Simpson’s-in-the-Strand. Both games are distinguished by an extraordinarily rare double rook sacrifice.

I wonder whether these protagonists of the past would have been remotely aware that their mental exertions on the chessboard would have survived to delight, enthrall and inspire millions of chess enthusiasts in centuries to come, in fact as long as the game of chess continues to fascinate the human brain.