Troubles, spies, loss and consolation: my cultural year so far

(Shutterstock)

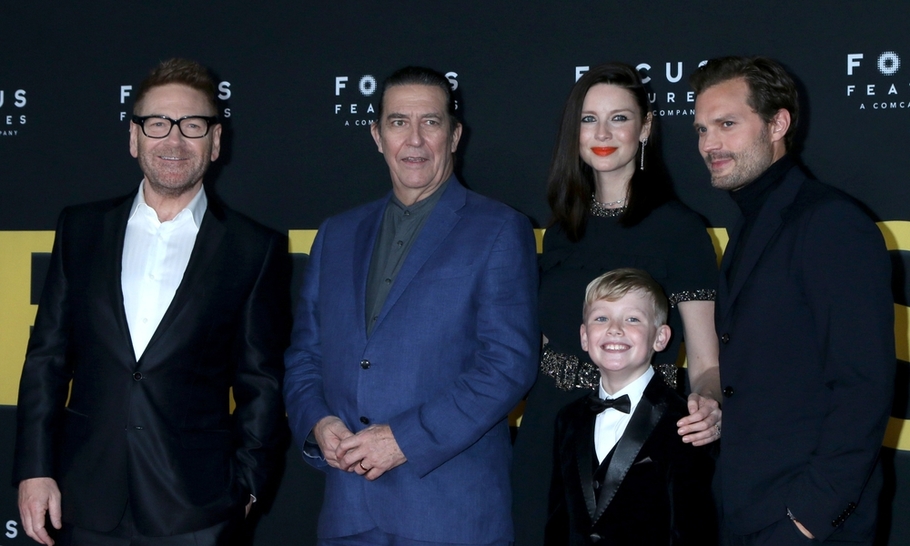

January has been packed with cultural highlights. Theatres and cinemas have re-opened and Kenneth Branagh’s new film, “Belfast” (released in Britain on 21 January) has already received seven nominations at the Golden Globe Awards and six nominations at the British Academy Film Awards. Set in 1969-70 it tells the story of the beginning of the Troubles through the experience of one family. The cast is terrific (Jamie Dornan, Ciaran Hinds, Judi Dench and John Sessions, in a brief cameo, are outstanding), the Van Morrison sound track is perfect and Branagh captures the sense of period through countless well-chosen details. It is one of the best British films in years.

Despite the bizarre Hershel Fink row at The Royal Court, the year has started well in the theatre. “Operation Mincemeat” opened at the Southwark Playhouse on 14 January and sold out almost immediately for the whole five-week run after rave reviews. The story is fascinating. In 1943 British intelligence set out to fool the Germans into thinking that Allied troops would land in Sardinia whereas their plan was to invade Sicily and use it as a launching pad to conquer Italy.

Members of British intelligence obtained the body of a tramp, dressed him as an officer and placed personal items on him identifying him as the fictitious Captain (Acting Major) William Martin. Correspondence between two British generals which suggested that the Allies planned to invade Greece and Sardinia, with Sicily as merely the target of a feint, was placed on the body which was dropped off the coast of Spain. The Germans were deceived and moved 100,000 troops from Sicily to Sardinia allowing the Allies to invade Sicily with little opposition.

But this hardly does justice to one of the most joyous shows in years, a fast-moving musical, full of twists and turns. The cast of five are superb, playing all the characters from Ian Fleming (then in British Intelligence) to the man who tracks down the tramp’s corpse. The show is smart, deeply moving and hilarious and deserves an immediate West End transfer.

The third series of “After Life” (Netflix, 14 January), written and directed by Ricky Gervais, is one of the TV hits of the Winter. It is funny but also deeply moving and sad, a kind of comedy noir. The main character, Tony (played by Gervais), is trying to pick up the pieces of his life after his wife’s death from cancer. He works for the local newspaper and the story moves between the characters in the office and a curious cast of locals, including Tony’s postman, a sex worker with a heart of gold, the members of a terrible local am-dram group and Emma, a nurse at the care home where Tony’s dad (David Bradley) was a resident and a grieving widow brilliantly played by Penelope Wilton.

Gervais is notoriously Marmite. People either loved or hated his breakthrough series, “The Office”, with its comedy of embarrassment. But it launched not only Gervais (David Brent), but Martin Freeman (Tim), Mackenzie Crook (Gareth) and Oliver Chris (Ricky). “After Life” also has a brilliant cast, including Wilton, David Bradley, Diane Morgan (Philomena Cunk in Charlie Brooker’s “Weekly Wipe” and Liz in “Motherland”), Ashley Jensen (“Extras”) and Paul Kaye (Dennis Pennis). But it’s the quality of the writing that makes “After Life” so memorable. It’s touching but never mawkish, moves between so many different characters each with their own story and deals with dark subjects from bereavement and dementia to loneliness, but is also one of the funniest TV series in years.

Michael Ignatieff’s latest book, On Consolation (Picador, 20 January), is a book of essays about coming to terms with loss. It is written as a history of ideas rather than as a personal book, telling the story of consolation from the Hebrew Bible, the Epistles of St. Paul and the Roman stoics to early modern thinkers like Montaigne and David Hume to witnesses of totalitarianism, including Anna Akhmatova, Vaclav Havel and Primo Levi and modern thinkers like Weber and Camus. But perhaps the most powerful essays are not about philosophy at all. There is a deeply moving essay about Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder and another about Cicely Saunders, “the good death” and the birth of the modern hospice movement.

Each chapter moves between a subject’s life and work but together they tell a larger story about changing ways in thinking of death and consolation. The book starts with the Jewish and Christian traditions but moves towards secular thinkers. “In the twenty-first century,” Ignatieff writes, “unbelief now commands the hearts and minds of many, though not all, of the people I know.”

And yet the final word in the book belongs to two deeply religious figures, Cicely Saunders and the Polish poet, Czeslaw Milosz. There is another fascinating shift in the essay on David Hume, which draws on Ignatieff’s 1980s TV drama about Hume and Boswell. Hume’s death, Ignatieff writes, “became a historical marker, a sign that a new way of dying, and hence a new way of thinking about consolation, was making its way into the world.”

In the chapter on Mahler, Nietzsche sounds a distinctly modern note. Ignatieff writes, “The only consolation entitled to respect, Nietzsche once said, was to believe that no consolation was possible.” And the chapter on “The Consolations of Witness” asks whether what sustained the great witnesses of Stalinism and the Holocaust was their faith in posterity and the moral influence they would have on future generations of readers. This is a powerful set of reflections on one of the great subjects, from the Bible to the Holocaust.

These works are just some of the cultural highlights from January. It has been an exciting start to the arts in the new year and one can only hope these works will all get the recognition they deserve.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout the pandemic. So please, make a donation.