Impeachment is a threat to Trump — but a risk for the Democrats too

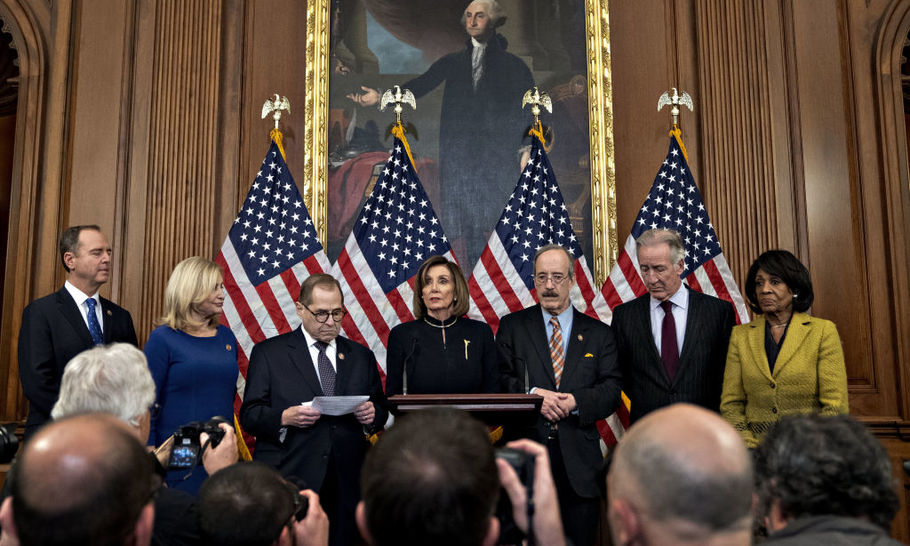

Nancy Pelosi, during a news conference after impeachment vote against Donald Trump (Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

There is something rotten in the United States of America. But is it the President or the Congress?

This week the House of Representatives impeached Donald Trump for “high crimes and misdemeanours”. The President will stand trial in the new year for abuse of power and obstruction of Congress. For him to lose office, the Senate, which acts as judge and jury, must vote by two thirds to remove him. The upper house has a Republican majority. Yesterday not a single House Republican voted for impeachment. Unless new facts come to light, it is nearly impossible for the Senate to evict Trump from the White House.

In truth, however, anything could happen. American politics is more unpredictable than it seems from inside the beltway. The calculation of the Democrats and the liberal media is that over time the gravity of the allegations will tell against the President. Ranged against the President is an array of witnesses —some of them whistleblowers, others diplomats— to testify that he conspired to undermine the presidential campaign of a former Vice-President, Senator Joe Biden, by using public money corruptly to solicit investigations by the Ukrainian President into a political rival. Once exposed, he is alleged to have obstructed due process and thereby subverted the Constitution.

The language of the indictment is measured, but in legal terms it is the equivalent of a broadside from a battleship. The first Article of Impeachment concludes thus: “In all of this, President Trump abused the powers of the President by ignoring and injuring national security and other vital national interests to obtain an improper personal political benefit. He has also betrayed the Nation by abusing his high office to enlist a foreign power in corrupting democratic elections.” Article 2 is equally strong on rhetoric, alleging that “Donald J. Trump has directed the unprecedented, categorical and indiscriminate defiance of subpoenas issued by the House of Representatives”. It alleges that the President is “a threat to the Constitution if allowed to remain in office, and has acted in a manner grossly incompatible with self-governance and the rule of law.”

Seen from Washington DC, this all looks pretty serious. And opinion polls suggest that a plurality, though not a majority, of voters agree with the Democrats that Trump’s conduct warrants impeachment.

Yet does any of it pass the “So what?” test? In the end, nothing came of the alleged conspiracy. No “personal political benefit” has in fact accrued to Trump. Biden’s candidacy may be fizzling out, but for reasons that have nothing to do with his son’s business dealings in Ukraine. Most importantly, it seems that no taxpayers’ money changed hands corruptly and no visible damage to national security has been done. For Trump voters, none of it amounts to a row of beans.

It is, then, far from clear that the impeachment of Trump will play out to the advantage of the Democrats. The American public takes the abuse of office, especially presidential office, extremely seriously. But the attempt to remove their head of state by any means other than election may itself appear to be an abuse of office. If the evidence against Trump stands up, let the voters, not the senators, decide to remove him next November.

The whole spectacle of impeachment has, seen from London, an archaic quality. Impeachment was, like most of the US Constitution, borrowed by the Founding Fathers from the supposedly tyrannical British. It was a characteristically 18th-century remedy for an 18th-century problem: corruption. Since that era, impeachment has fallen into disuse on this side of the Atlantic because British politics has, in general, ceased to be corrupt.

In the United States, by contrast, the abuse of office remains a genuine concern. Trump has certainly tested the system to its limits, but he has also been careful to respect the constitutional proprieties. He knows very well that even the President is not above the law. Nobody is more important to a property developer from Queens than his lawyer.

Unpredictable the impeachment process may be, but one thing is certain: while it effectively paralyses the Trump administration, it does not let the Democrats off the hook either. They still lack a candidate who is obviously qualified to take on Trump next year. The legal wrangling will be a distraction for both parties, but it is more likely to unite Republicans in defence of their champion.

The show of defiance by the President at a rally in Michigan was, as usual, over the top. His tweets were similarly uncompromising: “Can you believe that I will be impeached today by the Radical Left, Do Nothing Democrats, AND I DID NOTHING WRONG!” He added an implied warning that he might seek to curtail the power of Congress to impeach: “This should never happen to another President again. Say a PRAYER!”

Donald Trump’s most enduring achievement has been his mobilisation of popular anger against an unpopular political establishment. All power tends to corrupt, but in America absolute power belongs to the people, not the Congress.