Today’s UN ban on nuclear weapons: is it moral grandstanding?

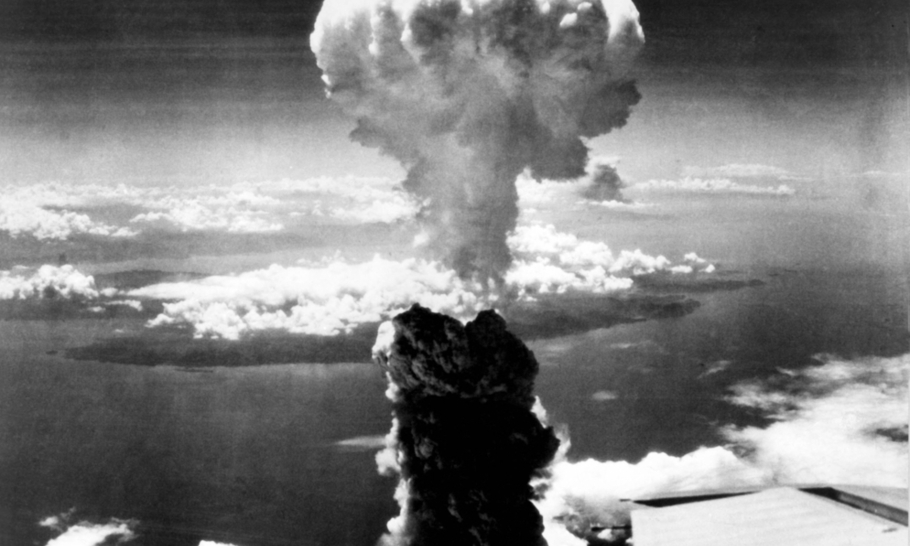

Nagasaki 1945 (Shutterstock)

My generation lived through the Cuban missile crisis. Our lives were threatened not by an invisible, spiky virus, but a nuclear mushroom cloud. Today, 22 January, after many years of campaigning and debate, the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, (the Ban Treaty for short) with 86 signatories, including 51 “states-parties”, comes into force. It has taken over three years to collect more than the 50 state signatures that were required for implementation of an agreement reached in 2017.

In the summer of 2017, a rolling conference convened by the UN General Assembly produced a legally binding prohibition of nuclear weapons, in the hope of their ultimate elimination. Developing, testing, producing, manufacturing, transferring, possessing, stockpiling, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons, or allowing nuclear weapons to be stationed on their territory, were all banned. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), the Treaty’s principal non-governmental mover and shaker, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize later that year. The Vatican celebrated the Treaty with a conference for the 40 or so campaigning organisations that had contributed to its creation. But I would guess worldwide few people knew then, or know now, of this treaty or its significance.

The existing nuclear powers were and are determined not to sign. So is the Ban Treaty another piece of paper on the shelf of the UN Secretary-General, not even to be honoured in the breach, just ignored? It’s far more significant than that, as both supporters and opponents would agree. The Treaty represents a growing global legal consensus concerning international humanitarian norms. An international regulatory body for its implementation will be set up – the Austrian government is preparing for a first meeting of states parties in late 2021 – and there is a legally time-limited opportunity for the nine existing nuclear powers to start what they have notably failed to do: negotiate the elimination of their stockpiles of nuclear weapons. Or, as former President Khatami of Iran replied to my question on the status of nuclear weapons in Shi’a Islam: “Haram, haram (prohibited) for both possession and use”.

Because of their immense destructive power and long-term consequences, nuclear weapons, along with chemical and biological weapons, are clearly a unique threat to humanity. But it has to be said that, as the Syrian and Iraq governments have demonstrated by using chemical weapons, this is no guarantee of future compliance with international law. And here is the rub. While it is just conceivable that public pressure and actual cost might persuade Britain to abandon Trident, neither of these pressures would make North Korea, China or Russia sign up to and become compliant with the Treaty. We have to acknowledge and accept the potentially asymmetric impact of pressure for total elimination of nuclear weapons. It’s a big ask. South Africa did not have any enemy on its doorstep in 1991 when it led the way and dismantled its nuclear warheads that the apartheid regime had developed, perhaps with Israeli help.

The renunciation of nuclear weapons by any country or countries requires prolonged diplomatic engagement and peace building. The conflict between India and Pakistan, both nuclear powers and embroiled in a bitter dispute over Kashmir dating from Britain’s withdrawal, is only one example. For all the Brexit talk about sovereignty, Britain’s own options are constrained by our membership of a defensive nuclear alliance, Nato. What would be the strategic implications of Britain’s adherence to the Ban Treaty? Again, decisions about nuclear weapons can only be made in the context of a national discussion about what we want Britain’s role in the world to be, and what we think security and responsible geo-politics should look like in the future. Apart from these questions, Nato’s total rejection of the Treaty should stimulate a much wider national discussion than the one intermittently taking place within the peace movements and the military about Trident.

Nato has been deploying powerful arguments. Michael Rühle, the main interlocutor for the alliance’s Emerging Security Challenges Division, does not pull his punches. He writes that advocates of the Ban Treaty “ignore the international security situation” , engage in “moral grandstanding” and that it “pulls the rug from under” the 1970 Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). The Ban Treaty reflects the frustration of many states in the global South at the failure of the NPT to change the nuclear weapons landscape. It challenges the doctrine of mutually-assured destruction. But the Ban Treaty is consistent with Article VI of the NPT, which commits states-parties to “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.” That more or less covers the process which led to the Treaty.

Religious opinion is increasingly vocal and united. The Pope, the Vatican and the British bishops, both Catholic and Anglican, have clearly called on the British Government to “forsake its nuclear arsenal”. This month the British Catholic bishops stated:

“On Friday 22 January 2021 the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons comes into force. This is an historic milestone on the path to nuclear disarmament and an opportunity to refocus on genuine peacebuilding rooted in dialogue, justice, respect for human dignity, and care for our planet.

In setting out the ‘moral and humanitarian imperative’ for complete elimination of nuclear weapons, Pope Francis reminded us that ‘international peace and stability cannot be based on a false sense of security, on the threat of mutual destruction or total annihilation.

We urge support for the Treaty and repeat our call for the UK to forsake its nuclear arsenal. The resources spent on manufacturing, maintaining and upgrading these weapons of mass destruction, should be reinvested to alleviate the suffering of the poorest and most vulnerable members of our society, for the Common Good of all peoples”.

But nuclear disarmament remains the dog that doesn’t bark in British politics.

If the Treaty does its job of making people once more aware of the terrible consequences of nuclear warfare, and if it initiates a national and international debate about a responsible geo-politics, what we mean by security, what sort of alliances we must make in the face of ruthless authoritarian regimes, it will have accomplished a great deal. The nuclear issue has largely disappeared from the manifestos of our political parties. The gulf between the settled opinion of the securocrats and politicians and the clear message coming from the faith communities, peace movements and what used to be called the non-aligned states of the global South, is daunting.

On 5 February this year the US-Russian Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty New Start, which caps each country’s nuclear weapons at 1,550, comes up for renewal or extension. China refuses to engage. Looking back on the near-nuclear disasters of the Cold War, the eventual outcome of an entrenched belief in a strategy of mutually assured destruction will probably be accidental ….mutually assured destruction.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout the pandemic. So please, make a donation.