Love and war: Thomas Hardy’s poetry

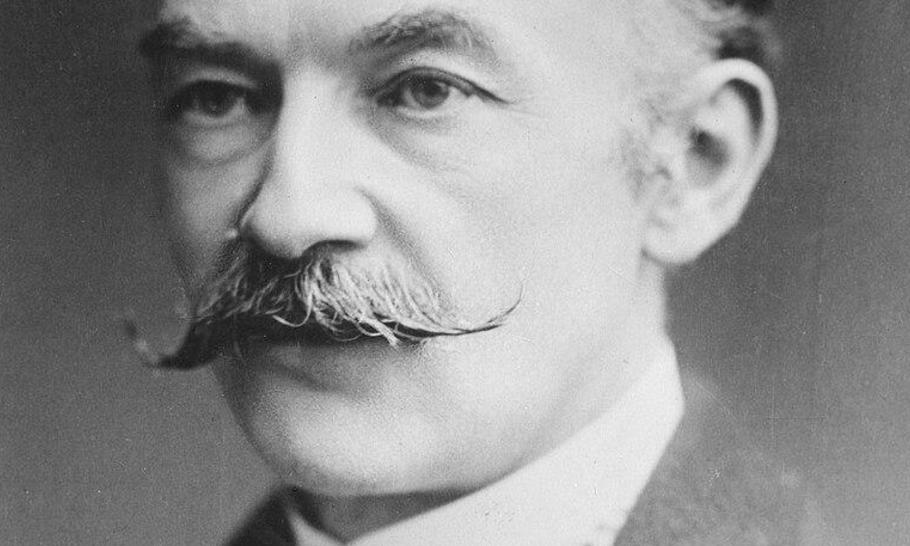

Thomas Hardy, c. 1910–1915

The sadness and dark cast of mind in the poetry of Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) appeals to the modern temperament. His ironic, pessimistic outlook, his acceptance of catastrophe and lack of consolation, match our grim view of the dangerous contemporary world. Samuel Hynes defined the obsessive ideas that determined the substance and style of Hardy’s poems: “infidelities of all possible kinds, the inevitable loss of love, the destructiveness of time, the implacable indifference of nature, the cruelty of men, the irreversible pastness of the past.” W. H. Auden concluded, “What I valued most in Hardy was his hawk’s vision, his way of looking at life from a very great height.” Here, I hope to cast new light on Hardy’s poems by comparing them to works on similar themes by Proust, Hemingway, Hopkins, Orwell and Henry James.

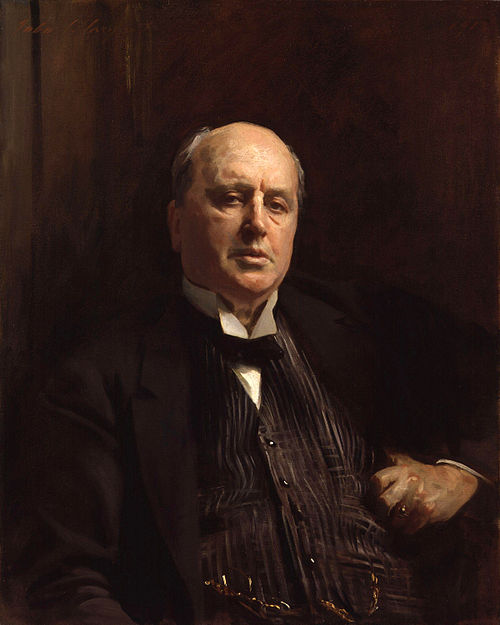

Henry James (1913), portrait by John Singer Sargent

“A Broken Appointment” (1901) portrays Hardy’s recurrent theme: disillusionment in love. Both 8-line stanzas repeat the opening four words. The sudden stark statement, “You did not come,” is both a protest and a lamentation. Numbed by the woman’s absence and grieved when he hears the hoped-for hour sound in the bell tower, the narrator is more tortured by her lack of compassion and loving-kindness than by her failure to appear on time or, indeed, at all.

The wounded lover bitterly accepts the fact, as he confesses and repeats in the second stanza, “You love not me.” She broke her promise and was cruelly disloyal: “I know and knew” it was the end of the affair. It’s now painful rather than consoling to recall that “Once you, a woman, came / To soothe a time-torn man.” Nothing’s more painful than to remember past happiness when he’s miserable. He then begs for pity, if not for love: “Was it not worth a little hour or more . . . even though it be / You love not me?” She’s not only broken her appointment, she also broken his heart. In “The Tower,” Yeats asked, “Does the imagination dwell the most / Upon a woman won or woman lost?” Hardy always emphasises the loss.

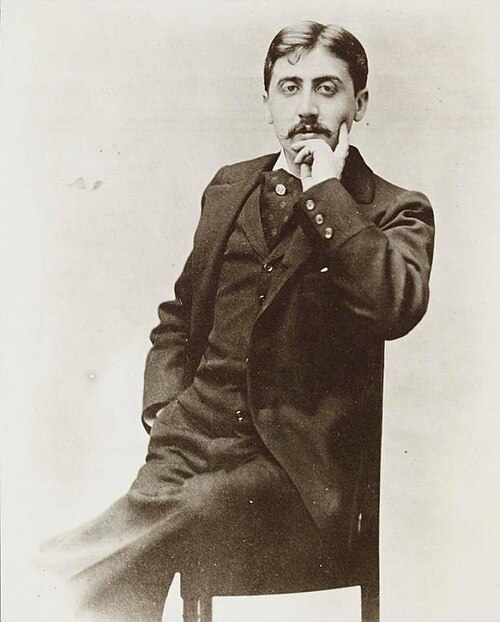

Two other wounded fictional heroes embody the theme that Hardy hints at. Each is tormented by the belief that the woman he loves has left them for another man. In Proust’s Swann’s Way (1913), the morally flawed Odette feigns illness and (alluding to Othello) begs her lover Charles Swann “to put out the light” before he leaves. When he returns home he’s suddenly struck by the thought that Odette is going to entertain a hated rival and sleep with him that night. Suspicious and jealous, Swann returns to her house, sees that her light is still on and (in a superb simile) that it sensuously “overflowed between the slats of her shutters, closed like a wine-press over its mysterious golden juice.” He suffers jealous agonies “as he watched that light, in whose golden atmosphere were moving, behind the closed sash, the unseen and detested pair, as he listened to that murmur which revealed the presence of the man who had crept in [like a serpent] after his own departure, the perfidy of Odette, and the pleasures which she was at that moment tasting with the stranger.”

Proust in 1900

In Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1926) the hero Jake Barnes—wounded and made impotent in the war—waits impatiently in a luxurious Parisian hotel for the faithless woman whom he loves:

At five o’clock I was in the Hotel Crillon waiting for Brett. She was not there, so I sat down and wrote some letters. They were not very good letters but I hoped their being on Crillon stationery would help them. Brett did not turn up. . . . She had not been in the bar either, and so I looked for her upstairs on my way out, and took a taxi to the Café Select. Crossing the Seine I saw a string of barges being towed empty down the current, riding high, the bargeman at the sweeps [oars] as they came toward the bridge. The river looked nice. It was always pleasant crossing bridges in Paris.

While distracting himself with commonplace correspondence, Jake expresses some self-deprecating wit. Drinking at the bar doesn’t help any more than letters, so he continues to search for Brett in her habitual café. Suddenly, the mood changes. By looking at the barges from the bridge, Jake can see that they carry no cargo and ride high in the water. Though he is also emotionally empty, he’s pleased by crossing the Seine from the Right to the Left Bank, and by observing the swift flow of the river that effortlessly carries the bargeman steering under the bridge. In all three works faithless women betray and torture their desolate lovers.

The subject of Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” (1900) is a small, quite ordinary ground bird with a squeaky chirp, not the poetically impressive and symbolic visionary birds in Shelley’s “To a Skylark” and Hopkins’ “The Windhover.” Hardy frequently alludes to Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale”: “Darkling I listen,” “spectre-thin,” “full-throated ease” and “fling his soul.” Hardy’s harsh opening stanzas describe a spectre-gray, desolate landscape that creates the gloomy mood of the narrator and drives all men back to the warmth of their domestic fires. Hardy over-emphasises the funereal ambience with “corpse,” “ death,” “ shrunken” and “fervourless”.

The mood suddenly changes when the narrator hears the surprising joyous song of the windswept “aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small / In blast-beruffled plume.” But Hardy, characteristically extinguishing all hope, finds no reason for its ecstatic sound. The thrush expresses “Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew / And I was unaware.” The narrator contrasts the bird’s innocence and intuition with his own bitter experience and knowledge. If the thrush, like the man, knew the real world, it wouldn’t sing, so the effect of his joyous song is painful and ironic. Hardy published this pessimistic poem in the London Times on December 31, 1900. It marked the end of the year and the century, anticipating the close of Queen Victoria’s reign and the eclipse of religious belief.

Two of Hardy’s greatest poems are based on major historical events: the sinking of a luxurious ocean liner, which seems to anticipate the Great War (which he describes in “The Man He Killed”) as well as the war’s precarious end. “The Convergence of the Twain (lines on the loss of the Titanic)” responds with bitter irony to the fatal crash of the “unsinkable” ship. On its maiden voyage from Southampton to New York on the night of April 15,1912, the liner struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic and sank with the loss of some 1,500 lives.

The first five stanzas of this modern version of Samuel Johnson’s poem “The Vanity of Human Wishes” satirise the Titanic as a lavish ship of fools that blindly crashed and was destroyed. Contrasting its ambitious plans with grim reality, Hardy evokes the salamander, a mythical beast supposed both to create and extinguish fire, and the powerful currents that thread the water and throb like the engines of the ship:

Steel chambers, late the pyres

Of her salamandrine fires,

Cold current thrid, and turn to rhythmic tidal lyres.

The furnaces and boilers that once propelled the ship are now sunk beneath the ocean. Sea-serpents crawl on mirrors once intended to reflect the splendors of the rich, and jewels “designed / To ravish the sensuous mind” are now dark, black and blind. Hardy rhetorically asks, “What does this vaingloriousness [do] down here?” The answer is “nothing”.

The last six stanzas describe the disaster, caused by lack of binoculars and insufficient lifeboats, by dark night, poor visibility, high speed and a treacherous wrong turn. The victims, shocked by immersion in the icy ocean, gasped for air as the water filled their lungs. Hardy attributes the collision to what he calls a Schopenhauer-like Immanent Will or all-powerful Fate. By “smart” he means fashionable, not intelligent:

And as the smart ship grew

In stature, grace, and hue,

In shadowy silent distance grew the Iceberg too.

The ship was predestined to collide with the iceberg, which seemed to exist solely for this purpose. Their consummation—suggesting sex with “ravish,” “sensuous,” “cleave” and “mate”—“comes, and jars two hemispheres” in the East and West. Hardy seems to have little sympathy for the hundreds of wealthy drowned victims, but his poem presciently predicts the impending war.

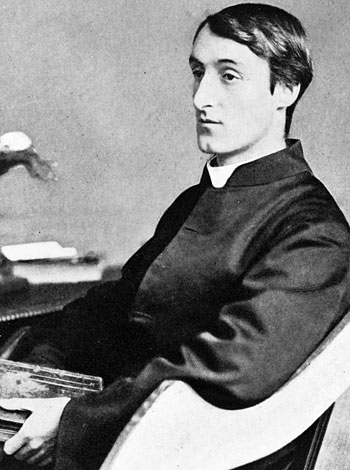

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem “The Wreck of the Deutschland” was also inspired by newspaper accounts of a disaster at sea. In 1873 the laws promulgated by the Prussian minister of culture, Adalbert Falk, had placed strict state controls over religious training and ecclesiastical appointments within the Catholic Church. Hopkins told a friend, “When in the winter of ’75 the Deutschland was wrecked in the mouth of the Thames and five Franciscan nuns, exiles from Germany by the Falk Laws, aboard of her were drowned I was affected by the account.” The disaster took place in England and martyred the cloistered Catholics fleeing from religious persecution.

Gerard Manley Hopkins

Robert Bernard Martin’s excellent biography of Hopkins gives more details. On December 7, 1875 the Times reported

the foundering of a German ship on a sandbank near the mouth of the Thames. It had been bound to New York from Bremen, and among more than a hundred passengers were five Franciscan nuns, refugees from Bismarck’s anti-Catholic legislation. . . . The captain of the Deutschland disastrously got off course, blinded by the dark and by the implacable storm. [The ship] shattered its propellers and began to roll helplessly before the breakers. . . . The seas were too rough for other ships to come to the rescue.

Hopkins writes that the nuns were

Loathed for a love men knew in them.

Banned by the land of their birth.

Rhine refused them. Thames would ruin them.

Hopkins focused on the five drowned nuns in the Thames and, Martin observes, “is brought face to face with one of the central mysteries of Christianity, the reason for the existence of suffering in a world created by a beneficent God”. Hardy does not share Hopkins’ religious view, nor focus on the victims in the Atlantic Ocean, but ascribes the disaster to malign fate.

“The Man He Killed”, written in 1902 during the Boer War, anticipates the trench battles in the Great War. The first rhymed quatrain describes a congenial meeting in a familiar traditional setting. The first-person narrator uses colloquial diction: “some old,” “sat us down,” “right many,” and the unusual rhyme of the redundant “old ancient inn” and “nipperkin,” a measure for drink:

‘Had he and I but met

By some old ancient inn,

We should have sat us down to wet

Right many a nipperkin!

The next contrasting quatrain thrusts the reader into the military front where the British soldiers are close enough to see the enemy. Mechanically obeying orders and committing licensed murder, they exchange fire and the narrator luckily survives:

‘But ranged as infantry,

And staring face to face,

I shot at him as he at me,

And killed him in his place.

Hesitantly repeating “I shot,” “because” and “my foe,” the soldier tries in vain to explain and justify his violence. He also attempts to reassure himself with “Just so” (rhyming internally with “my foe”), “of course” and “clear enough,” and undermines his argument with the contradictory “although”:

‘I shot him dead because—

Because he was my foe,

Just so: my foe of course he was;

That’s clear enough; although.

He next imagines the history of his supposed foe, whose reasons for enlistment were the same as his own. Both passive soldiers and potential victims were subject to external pressure:

‘He thought he’d ’list, perhaps,

Off-hand like—just as I—

Was out of work—had sold his traps—

No other reason why.

The final ironic quatrain, with the apparently tame but bitter “quaint and curious,” returns to the congenial bar at the beginning. The narrator concludes that he’s killed a potential friend in the meaningless war:

‘Yes; quaint and curious war is!

You shoot a fellow down

You’d treat where any bar is,

Or help to half-a-crown.’

Two analogous scenes by writers wounded in war illuminate Hardy’s dramatic narrative. Interchapter 3 of Hemingway’s first book, In Our Time (1925), repeats with considerable irony an English officer’s recollection of the Western front in the Great War. The narrator casually describes shooting the Germans as if they were hunting animals.

The first German I saw climbed over the garden wall. We waited till he got one leg over and then potted him. He had so much equipment on and looked awfully surprised and fell down into the garden. Then three more came over further down the wall. We shot them. They all came just like that.

“Climbed over the garden wall” sounds like a children’s song. The narrator is also physically close to his victim, waits till he’s most vulnerable and then “potted him.” The victim doesn’t realize that the snipers are close by and is “awfully surprised” when he’s shot, when he falls and when he’s dead. Three more Germans blindly follow the first soldier and are also killed. The last sentence criticizes the narrator’s “jolly good fun,” his indifference to death, and also how war has brutalised him.

Orwell’s account of his experiences in “Looking Back on the Spanish War” (1942) is closer to Hardy’s humane views. On the Aragon front in the spring of 1937, Orwell saw an enemy expose himself (in both senses) to gunfire. Not carrying a gun, he was holding up his pants after losing his belt or rushing toward the latrine. Like Hardy, Orwell identified with the vulnerable enemy, a “fellow creature” humanized by a tragicomic condition. Relying on personal feelings rather than on military orders, Orwell allowed the enemy to live and continue to fight:

At that moment a man, presumably carrying a message to an officer, jumped out of the trench and ran along the top of the parapet in full view. He was half-dressed and was holding up his trousers with both hands as he ran. I refrained from shooting at him. . . . I did not shoot partly because of that detail about the trousers. I had come here to shoot at ‘Fascists’; but a man who is holding up his trousers isn’t a ‘Fascist,’ he is visibly a fellow creature, similar to yourself, and you don’t feel like shooting at him.

The title of Hardy’s “ ‘And There Was a Great Calm’ (On the signing of the Armistice, Nov. 11, 1918)” comes from—to continue the storm-at-sea theme—Matthew 8:26: Christ “arose and rebuked the winds and the sea; and there was a great calm.” Hardy evokes the religious element with “years of Passion” and again asks the overwhelming question: Why had there been four years (in capitalised abstractions) of Despair and Anger, Care and Sorrows?

In “brute-like blindness” religious principles were mouthed but abandoned, and “‘Hell!’ and ‘Shell!’ were yapped [like] dogs at Lovingkindness.” Hardy absolutely rejects the comforting notion that “War is done!” and, after “the four years’ dance / Of Death,” that peace will last forever. The Spirit of Irony insists that there’s no way to halt the avalanche of Rage and Wrong. Hardy concludes that calm fell on the dead, but not on the wounded, the traumatised and the vengeful living:

There was peace on earth, and silence in the sky;

Some could, some could not, shake off misery:

The Sinister Spirit sneered: “It had to be!”

And again the Spirit of Pity whispered, “Why?”

(Ford Madox Ford took the title of his war novel Some Do Not, 1924, from this quatrain.)

Once again Hardy prophesied tempest, not calm, and he was right. The ultimate effect of the Armistice and the Treaty of Versailles was World War Two.

Hardy lamented the end of the Great War. Henry James, in a magnificently tragic letter of August 5, 1914, a week after the conflict broke out, lamented the beginning. Referring to the Austrian Emperor and the German Kaiser, he saw the end of civilisation and the extinction of the idea of progress that had dominated Europe since the Enlightenment in the 18th-century:

The plunge of civilization into this abyss of blood and darkness by the wanton feat of those two infamous autocrats is a thing that so gives away the whole long age during which we have supposed the world to be, with whatever abatement, gradually bettering, that to have to take it all now for what the treacherous years were all the while really making for and meaning is too tragic for any words.

Jeffrey Meyers published “Hardy and the Warriors,” New Criterion, 21 (September 2002), 34-40, on his relation to T. E. Lawrence, Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.