The Bank vs. the Treasury

The Bank of England left the base rate at 4 per cent last week. Cue the predictable headlines: inflation still sticky, growth flat, Britain not yet out of the woods. The Goldilocks dream of two per cent inflation, not too hot, not too cold, remains as elusive as a pink unicorn strutting down Threadneedle Street. In fairness, the Bank is not alone in missing its target; most developed world central banks have been wide of the mark for the best part of a decade.

But the real story was buried in the small print, and it shows just how far the Bank’s remit has crept in a quarter of a century. Back in 1997, when Gordon Brown granted it independence, the Bank had one job and one lever: keep inflation under control by moving the base rate. That neat “one tool for one target” orthodoxy, the Tinbergen Rule, was the whole rationale. The target was inflation, the tool was interest rates. Simple.

That remit collapsed after the crash of 2008. From then on the Bank reached for the real heavy machinery: quantitative policy. Quantitative easing created £900 billion of digital money between 2008 and 2022, funnelled into bond markets. It kept companies and jobs alive and, more conspicuously, inflated house prices. It also left us with low productivity, stagnant wages and a zombie economy.

Since 2022 the spell has been reversed. Quantitative tightening has already pulled £317 billion back out of the economy, effectively burning the magic money QE created. The plan was to destroy £100 billion a year until 2031, when the full £900 billion would have gone up in smoke.

QE was not a nudge on a dial. It was firing up the magic money machine, conjuring billions out of thin air and hosing it through the bond markets. Compared with that, moving the base rate looks like a screwdriver next to a JCB. QE and QT shape house prices, wages, state borrowing costs and whether firms live or die. Since 2008, those have been the Bank’s true levers, used not just to tame inflation but to steer growth, unemployment and financial stability.

Which brings us to last week. The Bank blinked, slowing the pace of QT from £100 billion a year to £75 billion. Why? Because the pain is already visible: unemployment nudging higher, housing flat, demand weak. Crucially, the cost of borrowing has soared for the government. When the Bank hoovers cash out of the bond market, gilts become scarcer and more expensive, and the state’s debt bill rises. By easing off, the Bank has effectively left an extra £25 billion in the market this year. That means potentially cheaper borrowing costs for the government. For Rachel Reeves, that reprieve may prove one of the most important developments of her early tenure, and she had nothing to do with the decision. The markets may not look like they are cutting her some slack, but in practice the Bank just has done. Less QT does not just soften the blow for households; it lowers the cost of state borrowing, the fiscal straitjacket throttling policy.

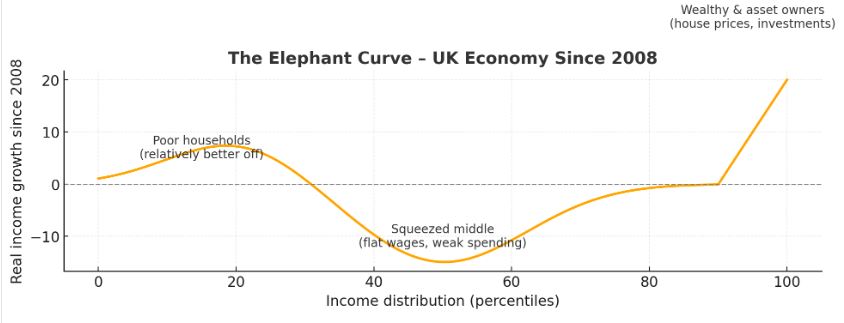

This matters because QT is not just “financial plumbing.” It is now the major lever by which the Bank now steers the economy. It also exposes Britain’s two-speed reality. QE enriched asset owners but left behind the wage-earning middle, the people who generate growth. For fifteen years they have endured flat incomes, rising costs and no productivity gains. The elephant curve in action: the poor tail inching up thanks to increases in the minimum wage and the welfare state, the middle slumping, the rich trunk shooting skywards on a feast of asset enrichment. And it is that middle class — the builders, accountants, window cleaners and car salesmen — that ultimately sustains long-term economic growth.

Illustration of the elephant graph of UK earnings growth

Which brings us to Liz Truss. The former Prime Minister seized on the Bank’s change of policy from QE to QT as proof that her mini-Budget in 2022 was sabotaged by a liberal elite conspiracy. Her evidence, set out on X/Twitter, had the sound of a rant in a pub after closing time. And yet, somewhere in the babble, there is a clue about the dysfunctional way Britain manages its economy.

On 4 August 2021 the Bank of England unveiled its QT game plan: no date, just a promise to drain the swamp… eventually. By 2 February 2022 it had quietly started, letting gilts expire. Then on 21 September the Bank went full arsonist, voting to torch bonds on a digital bonfire of pound notes.

QT is poison for bond markets because it floods them with extra supply just as demand is drying up, driving down prices and pushing up borrowing costs. Every gilt the Bank sells has to be bought with real cash from investors, which is then sucked out of circulation and locked away in Threadneedle Street, the very definition of taking money out of the system.

Two days after the Bank of England started burning money, Kwasi Kwarteng delivered his mini-Budget, demanding tens of billions of loans from the very same bond market out of which the Bank of England was sucking money and burning it. Cue instant chaos.

It was not the conspiracy of globalist financiers that Truss would have us believe. It was a farce of coordination. The Bank was draining the bath while Truss was trying to fill it. Markets concluded, not unreasonably, that the British household had lost the plot. That was Truss’s failure: rank stupidity, born of a failure to grasp the environment she was operating in.

If the problem with Truss was ignorance, the danger with Rachel Reeves may be the opposite. Like the Bank of England insider she purports to be, she’s convinced that she is utterly beholden to the Bank of England and the bond markets. And for now, she is right. The merest hint that the Treasury might lean on Threadneedle Street would spook investors and trigger a potential meltdown. But since 1997 the Bank has undergone a huge mission creep. It has drifted far beyond the Tinbergen Rule and reinvented itself as Britain’s economic witch doctor, wielding two tools and shaping not just inflation but the entire direction of the economy.

That goes far beyond the boundaries set in 1997, with little or no democratic mandate. The Truss crash was the most spectacular collision. The Reeves danger is subtler: becoming hostage to a central bank that dictates which of her policies can survive. Rightly or wrongly, the democratic mandate belongs to her; the Bank’s role should be to support, not to pre-empt, an elected Government.

So what is the answer? Not to strip the Bank of independence, as Donald Trump is trying to do to the Federal Reserve. That way lies disaster. But neither can we tolerate the current dysfunction, where the Government does not understand the Bank and the Bank behaves as though the Government were an inconvenience.

QE and QT must be treated as major policy decisions, explained as openly as interest rate changes. The Treasury and the Bank need structured, published forums for joint strategy, not to control each other but to avoid collisions. The UK should have a fiscal cabinet, with the OBR in attendance. And the Bank should be required to explain to ministers and the public not just its inflation forecasts, but also the wider consequences of its policies on wages, productivity and housing. Independence should not mean insulation.

The point is not to drag the Bank back under ministerial control, but to restore balance between monetary technocracy and democratic mandate. Britain cannot afford another Truss-style blind crash, nor a Chancellor who feels permanently hostage to Threadneedle Street. The Bank of England was made independent in 1997 to keep politics out of monetary policy. A quarter-century on, independence has morphed into mission creep. It may be time to modernise independence, not to weaken it, but to make it work with, not against, the elected government.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.