‘The Great Gatsby’: impossible dreams

In 1991 Cambridge University Press published a 225-page edition of The Great Gatsby (1925), expertly edited by Matthew Bruccoli and Fredson Bowers. It has a chronology, a 46-page introduction, elaborate textual notes and detailed explanatory notes. So it’s not at all clear why Cambridge has just published another edition.

As if propelled by automatic pilot, the dynastically named James L.W. West III can’t stop editing The Great Gatsby, and has re-edited and re-re-edited the novel at least 8 times in the last 8 years. His latest effort, The Cambridge Centennial Edition (2025, 278p, £20)—is a pretty book with a spooky nocturnal cover that looks more like Poe’s House of Usher than Gatsby’s splendid pile. This edition features minimal annotations, 27 illustrations and a 30-page introduction by Sarah Churchwell.

Author of Careless People (2013), a first-rate book on Fitzgerald, Churchwell’s mostly intelligent and perceptive introduction concludes, “the novel is about our dreams of transcending reality. . . . If the novel’s great sin is carelessness, Fitzgerald’s elegy for Gatsby becomes his requiem for the utopian dreams of the nation that succumbed to it.”

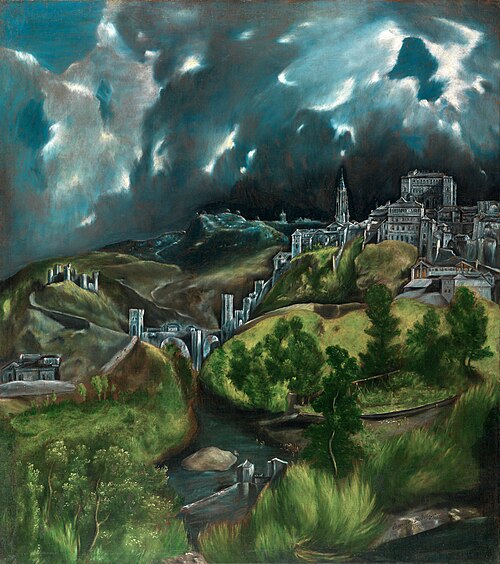

But Churchwell careens off the rails when devoting six pages to a single sentence. The narrator, Nick Carraway, looking back at the events at the end of the novel, says: “I see it as a night scene by El Greco: a hundred houses, at once conventional and grotesque, crouching under a sullen, overhanging sky and lustreless moon.” El Greco’s View of Toledo (1600, Metropolitan Museum, New York), reproduced twice in this book, does not match this description. This painting shows the hill town of Toledo (50 miles southwest of Madrid), seen from below the Tagus River and beneath a tempestuous sky, dramatically streaked with white clouds. The Roman Alcántara bridge leads up through curved dark green hills to three main monuments: the spire-topped cathedral, the grey façades of the Castle of San Servando and the Alcázar (royal palace). El Greco painted only two landscapes. Unlike his aristocratic portraits and swooning saints, the landscapes do not have feverishly elongated and exaggerated human figures, which Churchwell calls “distorted perspectives and grotesque shapes”.

El Greco View of Toledo

She quotes Somerset Maugham on El Greco (did his friends call him “El”?) in The Moon and Sixpence (1919) and more elaborately in Of Human Bondage (1915). In fact, both Nick Carraway and Maugham describe El Greco’s second landscape, View and Plan of Toledo (1608, El Greco Museum, Toledo). Unlike the Met’s more famous View of Toledo, the View and Plan actually has “a hundred houses . . . crouching under a sullen, overhanging sky”—but not a “lustreless moon.” In the foreground a pale young man, with a wide white ruff and row of buttons on his green velvet jacket, holds a large plan of the city streets. The plan touches a cottony cloud that somehow supports a model of the Tavera hospital. In the middle ground, a long stream of grey buildings sweeps along the curved brown hillside. In the background, acrobatic angels perform celestial somersaults as the patchy blue sky tries to break through the heavy dark clouds.

View and Plan of Toledo

Churchwell is also unaware of Maugham’s most significant and more critical discussion of El Greco. The “mysterious secret” of the painter that so troubles Philip Carey in Of Human Bondage—as Maugham finally explains in his Spanish travel book Don Fernando (1935)—is homosexuality. Maugham argues that El Greco “was homosexual. . . . In this abnormality lies the explanation of his pictures that fail to achieve ultimate greatness.” The absence of evidence allows Maugham to speculate that El Greco’s eccentric anti-naturalistic style, his sublimated passion, manic ecstasy and rapturous transfiguration of the flesh, his “tortured fantasy and sinister strangeness,” derived from his homosexual “idiosyncrasy and abnormality.” The queer Maugham strongly identified with El Greco, and took the artist’s neurosis and degeneracy as evidence of his homosexuality. Hemingway also thought El Greco was homosexual. In Death in the Afternoon (1932) he asks about the artist, “Do you make him a maricón? . . . Do you think all his citizens were queer?”

Churchwell most unconvincingly claims, based on the wrong Toledo landscape, that “West Egg becomes, like Toledo, a grotesque, nightmare city,” that “Nick views his experience of West Egg as a night scene by El Greco: a nightmare version of a city on a hill,” and that “El Greco painted the mystical in the modern world, and so did Fitzgerald.” Straining for a new interpretation, she produces an absurd non sequitur about Fitzgerald.

Several essential annotations are missing from this edition:

95- “I’d like to just get one of those pink clouds and put you in it and push you around”—An ironic allusion to the story of Paolo and Francesca in Canto V of Dante’s Inferno.

108- “Broadway had begotten upon a Long Island fishing village”— John Donne, “The Definition of Love”: “[Love] was begotten by Despair / Upon Impossibility.”

40- “shawls beyond the dreams of Castile”—“The potentiality of growing rich beyond the dreams of avarice,” quoted in James Boswell, Life of Johnson.

97- “Then I went out of the room and down the marble steps into the rain”—inspired the conclusion of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms (1929): “After a while I went out and left the hospital and walked back to the hotel in the rain.”

61-63- The catalogue of humorous and absurdly named guests at Gatsby’s party comes from the Crawleys’ dinner party in chapter 51 of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1848) and from the Cyclops chapter of Joyce’s Ulysses (1922).

45- “probably transported complete from some ruin overseas”—alludes to Isabella Stewart Gardner’s mansion in Boston and William Randolph Hearst’s castle, San Simeon, in southern California.

23, 160- In a roadside advertisement for the oculist, who represents God or Conscience, “the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic—their retinas [i.e., irises] are one yard high. . . . [His eyes] brood on over the solemn dumping ground. . . . The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg had just emerged, pale and enormous, from the dissolving night.”—The eyes may ironically allude to the Freemasons’ Eye of Providence or All-Seeing Eye, which represents the watchful care of the Supreme Architect. The large eye, surrounded by a blue background, radiates streaks of gold.

Eckleburg’s eyes appear in the Valley of Ashes, which suggests the Valley of God’s Judgment of evildoers in Joel 3:12: “Let the heathen be wakened, and come up to the valley of Jehoshaphat: for there will I sit to judge all the heathen round about.”

There’s an important echo of John Keats’ sonnet on a Renaissance poet’s translation from Greek, “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer”:

36- “casual watcher in the darkening streets”—“Then felt I like some watcher in the skies.”

Two other phrases echo Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale”:

96- “where there was no light save what the gleaming floor bounced in from the hall”—“here there is no light, / Save what from heaven is with the breezes blown.”

179- “half in love with her”—“half in love with easeful death.”

The biographical influence of Keats is also important. Both Keats and Gatsby idealised and were inspired by women—Fanny Brawne and Daisy Buchanan (partly based on Ginevra King)—who were hollow at the core and unworthy of their sacrificial love.

Many editions of The Great Gatsby were greatly enhanced by a stunning dust jacket that suggests the mystery and attraction of money and urban life. A woman’s face with bright pink eyes, a long teardrop and alluring red lips emerges from a dark blue sky. Below her are a skyscraper and city buildings illuminated by circular carnival lights and exploding yellow fireworks. This painting was missing from the pirated teaching copy of Gatsby that I bought in Taiwan in 1966. Each chapter, edited by an American teacher, has questions, notes on the text, significant words and “interesting expressions.” The first two pages of my copy are heavily annotated with Chinese characters, after which the student gave up.

Fitzgerald’s most perfectly realised work of art reveals a confident mastery of his material, a fascinating if sensational plot, a Keatsian ability to evoke a romantic atmosphere, a set of memorable and deeply interesting characters, a witty and incisive social satire, a surprisingly effective use of allusions, an ambitious theme of corrupted idealism and a silken style that seems as fresh today as it was a century ago.

Nick Carraway sympathetically describes Gatsby’s past. The chameleon has assumed many roles: poor provincial, ambitious youth, disciple of rich mentors, World War One soldier, Oxford scholar, wealthy bootlegger and reformed criminal. He’s now the owner of a mansion, a lavish spender and a furtive host. More heavily equipped, he resumes his knightly quest to win Daisy — ad astra per aspera — expecting to secure the glittering prize after five years of unwavering devotion and financial investment.

Many brilliant and memorable phrases appear in the novel:

-The Buchanans lived “wherever people played polo and were rich together.”

-When Daisy asks if friends miss her in Chicago, Nick gallantly and ironically replies: “The whole town is desolate. All the cars have the left wheel painted black as a mourning wreath, and there’s a persistent wail all night along the north shore.”

-After Nick Carraway warns Gatsby, “You can’t repeat the past,” Gatsby unrealistically insists, “Why of course you can!”

-With consummate boredom, Daisy asks, “What’ll we do with ourselves this afternoon? and the day after that, and the next thirty years?”

-Gatsby tells Tom, “in her heart she never loved anyone except me!,” meaning she only loved Tom with her body.

-Nick loyally reassures the ex-racketeer Gatsby, “They’re a rotten crowd. . . . You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.” (We don’t know how the strong, athletic Tom Buchanan evaded military service.)

-“They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness.”

In the novel Jordan Baker has advanced her career and increased her fame by cheating at golf: “She was incurably dishonest. She wasn’t able to endure being at a disadvantage.” Billionaire Trump has the same flawed character and behaves in the same way.

The garage-owner Wilson (slyly named for Edmund Wilson) has always been timid and humble. But he becomes violent and aggressive when Tom Buchanan falsely tells him that Gatsby has killed Myrtle, his unfaithful beloved wife, in a hit-and-run car accident. Wilson then kills Gatsby, who’s punished for Daisy’s crime. The novel leaves readers wondering, if Gatsby had not been shot, whether Daisy would have left Tom for him or remained in her luxurious but loveless marriage.

This edition does not mention Gatsby’s important influence on an artist, a film director and two novelists. When Gatsby displays his luxurious pile of shirts, he reveals his extreme materialism and offers haberdashery as well as love. Daisy, frequently characterised and made unreal as a disembodied voice “full of money,” begins to sob when she realizes that his entire ostentatious life has been created solely to impress her. In Forever Picasso, Roberto Otero recalls a lavish dress-up scene straight out of Gatsby: “Today Picasso greets us surrounded by shirts. There are shirts on the sofa, shirts on the stairs, shirts on the floor, shirts draped over a gigantic package of pencils and shirts on the layout of a book.”

Gatsby shot dead and floating in his swimming pool influenced the conclusion of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) when William Holden is shot dead in Gloria Swanson’s pool. Scott and Zelda (part-models for Gatsby and Daisy) inspired the dazzling, reckless and trouble-making couple, Shamus and Helen, in John le Carré’s The Naïve and Sentimental Lover (1971), whose title he borrowed from Friedrich Schiller.

Wilder, c. 1942

Fitzgerald also had a powerful influence on the major contemporary novelist James Salter. In Gatsby Nick, driving from Long Island into Manhattan, has great expectations: “The city seen from the Queensboro Bridge is always the city seen for the first time, in its first wild promise of all the mystery and the beauty in the world.” Salter also romanticises New York in his prose poem Still Such (1992): “Down Fifth Avenue with the tail-lights, dark, the wet streets gleaming. . . . Dawn near, the whole city for your happiness.” In his last novel All That Is (2013) the city, wealthy and shining, promises beauty and sex: “the brilliant theater of the great store windows, mansions of plenty, the prosperous-looking people. . . . The city was brilliant and vast. The shops were lit along the avenues as they passed.” Salter had Fitzgerald’s great theme of loss in love in his literary bloodstream.

The Great Gatsby brilliantly expresses some of the dominant themes of American literature: the idealism and morality of the Midwest (where most of the characters originate and where Nick returns at the end of the novel) in contrast to the materialism and corruption of the East (where the novel takes place); the frontier myth of the independent self-made man; the attempt to escape the guilty present and recapture the innocent past; the predatory power of rich and beautiful women; the limited possibilities of love in the modern world; the heightened sensitivity to the promises of life; the doomed attempt to sustain illusions and recapture the American dream.

Jeffrey Meyers grew up on Long Island. When he stood in King’s Point on the tip of the Great Neck peninsula and looked across Manhasset Bay, he saw—as Gatsby did—the promising lights on the opposite shore. He has edited The Great Gatsby and Tender Is the Night (both Everyman, 1993), and published Scott Fitzgerald: A Biography (1994), reprinted 2014 and still in print.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.