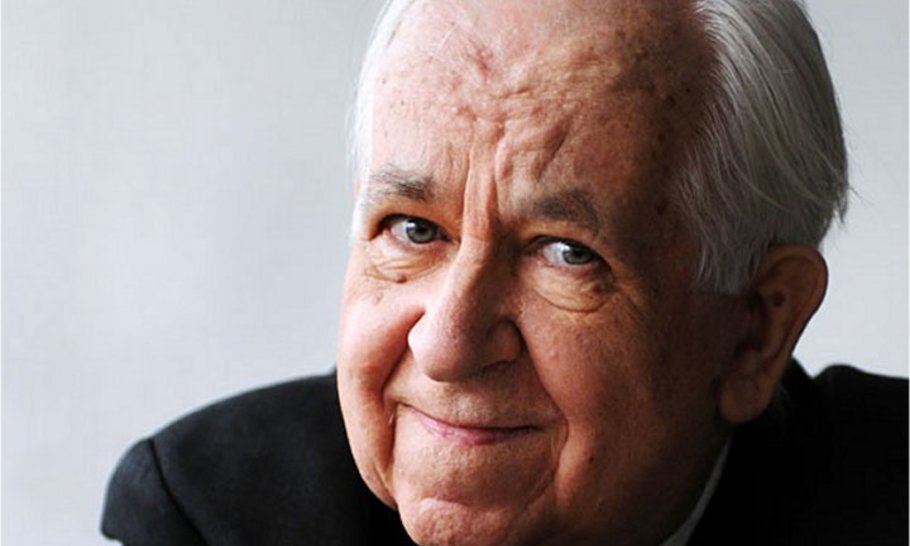

The doyen: Leonard Barden

(Shutterstock)

Leonard Barden’s life has been unusual. His father was a dustman. He learnt chess at grammar school and sharpened his play in air raid shelters during the war. He never called himself a prodigy, yet by the early 1950s he was among the strongest players in the country. His career took a new turn when his mentor, Julius du Mont, suffered a stroke. Barden was asked to take over as chess columnist for The Guardian.

Len (as his friends call him) gave up competitive chess early. After a poor showing at Hastings in 1961–62, he decided tournament play was no longer worth the effort. His last appearance was in early 1962, when he thrashed me in a simultaneous display. I had earned my seat by finishing runner-up in the London Under-14 Championship. The game was quick and ruthless: 1. Nc3 Nf6 2. e4 d5 3. e5 d4 4. exf6 dxc3 5. bxc3 gxf6 6. Qh5. From that point, Len was in complete control. Soon after, he walked away from serious play and turned to journalism.

I met many of his contemporaries—Penrose, Clarke, John Littlewood, Franklin, Wade. Against them I scored thirteen wins and two losses. But Len was a harder man to pin down. He became known less for his own results than for backing others. He encouraged Jim Slater, the financier who poured money into British chess, and he wrote tirelessly in the Evening Standard, Financial Times and Guardian about young players coming through.

Then, in 1969, he returned to active play. British weekend tournaments were thriving by then, and his reappearance was treated like the return of an old champion. He was a player, a writer, a theorist, and a promoter of events, often persuading sponsors such as Jeremy Morse of Lloyds Bank to put up money. His influence was everywhere. And on the board, he had not lost his edge.

At the Glasgow International of 1969, he was leading until the last round, when I managed to beat him—an echo of the simul game seven years earlier, but with the result reversed. Five years later, in 1974, he was the arbiter who gave me the verdict in an unfinished game against Jon Speelman. It was a controversial decision: the position looked level, but adjudications were the rule then, and his ruling secured me first prize.

He came to my aid again when the Slater fund was set up to reward Britain’s first grandmasters. Some doubted whether my rating was high enough to qualify. Len made sure the committee accepted my case. I received both the £2,500 prize and, soon after, the GM title at the Haifa Olympiad in 1976.

Len has been everywhere in British chess. He has survived when others fell away. Most of all, he has the nose for a story, the instinct that makes a journalist worth reading. For that reason he remains, after decades, the longest-serving and most widely read chronicler of the game.

Leonard Barden, now 96, is the longest-serving chess journalist in the world. He was born Leonard William Barden in Croydon on 20 August 1929. He became joint British Champion in 1954 and tied for first again in 1958, though he lost the play-off to Jonathan Penrose. He won Paignton in 1952 ahead of Grandmaster Yanofsky, and tied for first at Bognor 1954 with Grandmaster O’Kelly de Galway. At Hastings 1957–58 he finished fourth, behind Keres, Gligoric and Filip, all leading players from Eastern Europe. He was playing at International Master level, though the title was never given to him.

Between 1952 and 1962 he represented Britain in four Olympiads. After that he turned mainly to writing, junior development, and grading. In 1956 he became chess correspondent of The Guardian, a post he still holds 69 years later. His Evening Standard column, started in 1959, ran for more than six decades and set the world record for the longest-running daily chess column by a single writer. He has also written several popular chess books.

The game below shows Barden’s victory over Penrose at the 1959 British Championship, held in York. The previous year Penrose had beaten him in Hastings. Here Barden gained his revenge with a sharp exchange sacrifice and a clear finish.

Leonard Barden vs. Jonathan Penrose

British Championship, York, August 1959, rd. 3

- e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 a6 4. Ba4 Nf6 5. O-O Be7 6. Re1 b5 7. Bb3 O-O

This quick castling signal the Marshall Attack (7… d6 is normal). Barden accepts the challenge…

- c3 d6

… and Penrose reconsiders, reverting to traditional lines.

- h3 Na5 10. Bc2 c5 11. d4 Qc7 12. Nbd2 Be6 13. dxe5 dxe5 14. Ng5

A line associated with Boleslawsky

14… Bd7 15. Nf1 Rad8 TN

Penrose’s novelty. 15… h6 was the known move. In a clear vindication of human analysis, the engine selects these two moves as its primary selection.

- Qe2 g6 17. Ne3 Bc8 18. a4 c4 19. axb5 axb5 20. Rd1

- Nf3 may have been stronger, an observation with silicon approval.

20… Rxd1+ 21. Qxd1 Rd8 22. Qe2 b4

This gives White a small edge. Better was 22… Bb7 or …Kg7.

- Rxa5!

The exchange sacrifice that breaks Black’s position.

23… Qxa5 24. Qxc4 Rf8 25. Nxf7 Kg7

Here, the computer shouts foul! The move is a serious error. If Black instead proceeds with, 25… bxc3 26. Nxe5+ Kg7 27. Qxc3 Qxc3 28. bxc3 Bb7 29. f3 Bc5, the position is equal.

- Nf5+ gxf5

26… Bxf5 is worse: 27. Bh6+ Kg8 28. Nxe5+ and White wins.

- Bh6+ Kg6 28. Bxf8!?

- exf5+ was stronger, leading to a forced win.

28… Bxf8 29. Nh8+?!

This throws away the cleanest win. 29. cxb4 was decisive.

29… Kh6 30. Qxc8 Kg7 31. Qe6

- Qxf5 would have kept control.

31… Qa1+ 32. Kh2 Qxb2??

A fatal mistake. 32… Qa7 would have held.

- Bb3 h5 34. Qf7+ Kxh8 35. Qxf8+ Black resigns 1-0

Penrose does not wait for the denouement, 35… Kh7 36. Qf7+ Kh6 37. Qxf6+ Kh7 38. Bf7 Qxf2 39. Qg6+ Kh8 40. Qg8 checkmate.

Ray’s 206th book, “ Chess in the Year of the King ”, written in collaboration with Adam Black, and his 207th, “ Napoleon and Goethe: The Touchstone of Genius ” (which discusses their relationship with chess) can be ordered from both Amazon and Blackwells. His 208th, the world record for chess books, written jointly with chess playing artist Barry Martin, Chess through the Looking Glass , is now also available from Amazon.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.