Wyndham Lewis and the Vorticists

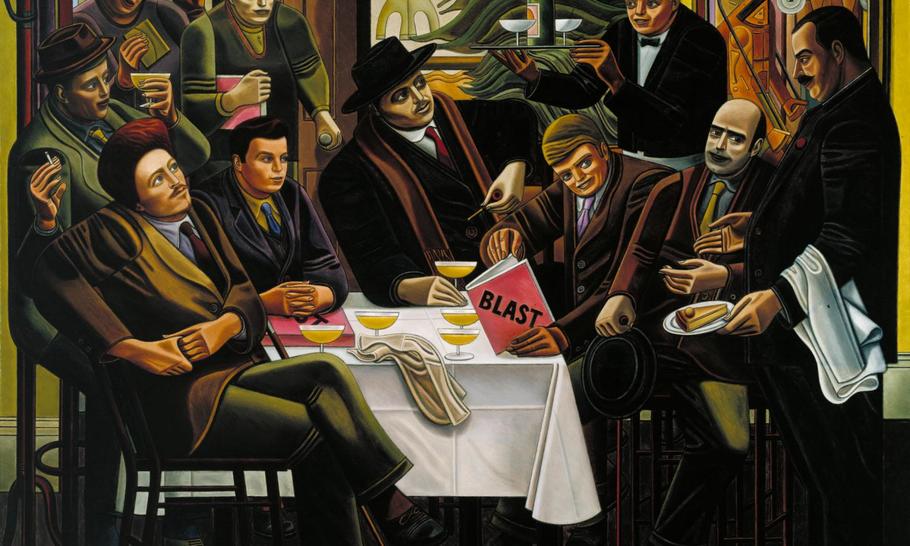

The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel: Spring, 1915 1961–2, William Roberts

The Vorticists were a dynamic group of painters who burst upon the English art scene in the years before the Great War. They aimed to synthesize the innovative and iconoclastic aspects of Post-Impressionism, Expressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, and Imagism in poetry, and oppose the traditional passéistes of the Royal Academy. Wyndham Lewis, the genius loci, declared: “At the heart of the whirlpool is a great silent place where all the energy is concentrated, the stationary moment amid chaos, the still point in a raging whirlwind. And at that point is the Vorticist, on a vertiginous, but not exotic, island in the placid respectable archipelago of English art.”

James King’s ‘Our Little Gang’: The Lives of the Vorticists (Reaktion, 230p, £30/$45) is well-illustrated, and plans to show “why Vorticism came into being, its accomplishments and, especially, its practitioners.” But he does not realise the full implications of his excellent subject. He quotes too many imperceptive contemporary reviews, and his sketchy and insubstantial biographical chapters read like entries in a reference book. The Vorticist painter Frederick Etchells, unaccountably, is not included in this volume.

King could more effectively have focused on Lewis—the only true genius of the group, who created Vorticism and edited the two volumes of their magazine BLAST (1914-15)—and shown how all the other artists related to him. But King undermines the significance of his own book by his extreme and unrelenting hostility to Lewis. He calls him indecisive, inept, oafish, condescending, manipulative, jealous, suspicious, misogynistic, rude, abrasive, cantankerous, oppressive, demanding, self-serving, outrageous, insulting, threatening, brutal and caustic; an egoistic braggart, a tremendous bully and an expert in cadging money. King doesn’t appreciate Lewis’ extraordinary talents, nor see that he had to face a lifetime of extreme poverty and serious illness, harsh criticism and lack of recognition.

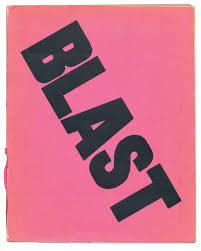

Cover of the first edition of Blast, 1914

Ezra Pound, who provided the title of this book, gave an infinitely more perceptive account of Lewis’ extraordinary qualities: “He possessed not merely knowledge of technique and skill, but intelligence and knowledge of life . . . he was a whirlwind of force and emotion.” Pound insisted that Vorticism would never have existed without Lewis: “the vitality, the fullness of the man! Nobody knows it! Nobody has any conception of the volume and energy and the variety.”

By contrast, King wildly overrates the modest achievements and importance of Helen Saunders and Jessica Dismoor, and trots out the feminist clichés: “women were closeted in the patriarchy. . . . The crucial roles of Saunders and Dismorr have often been erased.” But vaguely stating that Saunders “injected her own point of view” does not make her a major artist. Dismorr’s Portrait of a Young Girl is brown and dull, and in Saunders’ words, seems to be “spreading mud everywhere”. King mistakenly describes Saunders and Dismorr as Unseen and Overlooked, Uninvited and Unwanted, but they were part of the Vorticist group, lucky to be included and remembered today for their participation.

Saunders and Dismorr were not, as King affirms, “terribly proper women”. He does not mention the crucial fact that Saunders and Dismorr, as well as the artist Kate Lechmere and Lewis’ patron Mary Borden Turner—born between 1885 and 1887 and a few years younger than Lewis— all slept with him. Free love prevailed in these bohemian circles. After a brief absence from a meeting, the critic T.E. Hulme declared, “the steel staircase of the emergency exit at Piccadilly Circus Train Station was the most uncomfortable place in which he had ever copulated”.

The artists came from very different backgrounds. Lewis, David Bomberg, William Roberts and Henri Gaudier were poor; Edward Wadsworth, Saunders and Dismoor were wealthy. But they all defied their families to study art. Of the seven members, all but the Frenchman Gaudier trained at the Slade School of Art in London.

Bomberg, an isolado who sat on the margins of Vorticism, had the same tough, defiant personality as Lewis. These artists were torn “between abstraction and illustration, between pure form and literal representation”; between the tranquil and the turbulent “where tremendous forces of energy are channeled together in a single moment” and Euclid is buried deep in the living flesh.

BLAST mixed text and reproductions, and used different sized typefaces. It blasted socialists, mystics, pacifists and conservative politicians, and blessed those who challenged society’s norms, including boxers, aviators, music-hall performers and suffragettes. Lewis attacked romanticism, sentimentality and humanism, but was also serious beneath the strident surface. The first BLAST contained the opening chapter of Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier, Pound’s poetry, Lewis’ fantastic play The Enemy of the Stars, a story by the young Rebecca West, a review of Wassily Kandinsky’s On the Spiritual in Art, and drawings by Lewis, Gaudier and Jacob Epstein. This powerful movement forced modernism into a provincial, philistine England, but the Great War destroyed Vorticism before it could fully develop. Lewis, Bomberg, Wadsworth, Roberts and Etchells went to war; Gaudier and Hulme were killed.

King’s book has significant errors. Knuckle-dusters are worn at the front (not back) of the hand. King quotes but does not comment on an absurdity: after Bomberg during the war had deliberately shot himself in the foot, the limping cripple was “assigned the role of runner.” He doesn’t see that Bomberg’s Family Bereavement was influenced by Edvard Munch’s Deathbed paintings. Jacob Epstein’s sculpture Rock Drill does not “look confused and disheartened”; there’s no expression on its blank metallic visor. Lewis’ bitter quarrel with Roger Fry at the Omega Workshops was not merely a “brouhaha”; Fry first secretly increased his own fees, then stole Lewis’ commission. In Shakespeare’s play Timon of Athens, illustrated by Lewis, Timon did not merely offer “rocks and lukewarm water” to his hated guests, but served human flesh at his cannibal feast. King says that Lewis supported the Third Reich, but doesn’t mention that he recanted his misguided and damaging views in 1939. King also makes meaningless generalisations that apply to all artists: “they explored various paths,” “they searched for new ways to explore advanced art,” “they explored ways in which they could transform their work,” “he wanted to harness his skills to create his own distinctive work.”

King’s descriptions of the paintings are disappointing, and seven important pictures (the first four by Lewis) need more serious analysis. Smiling Woman Ascending a Stair (1912) echoes the title of Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No.1) (1911). The unusually tall, hard woman—with angular shapes of her body—is dressed in a long brown gown, and has one foot peeping out below and touching the stair. She has a twisted head, blacked-out triangular eyes, sharp cheekbones, pointed nose and huge teeth protruding from a grimacing (not smiling) mouth. She seems to be attacked from behind by a dark crouching figure pointing a sharp lance and jagged spear at her. Indifferent to or unaware of the thrust, she continues her stately ascent.

Marcel Duchamp: Nude Descending a Staircase (No.1) (1911)

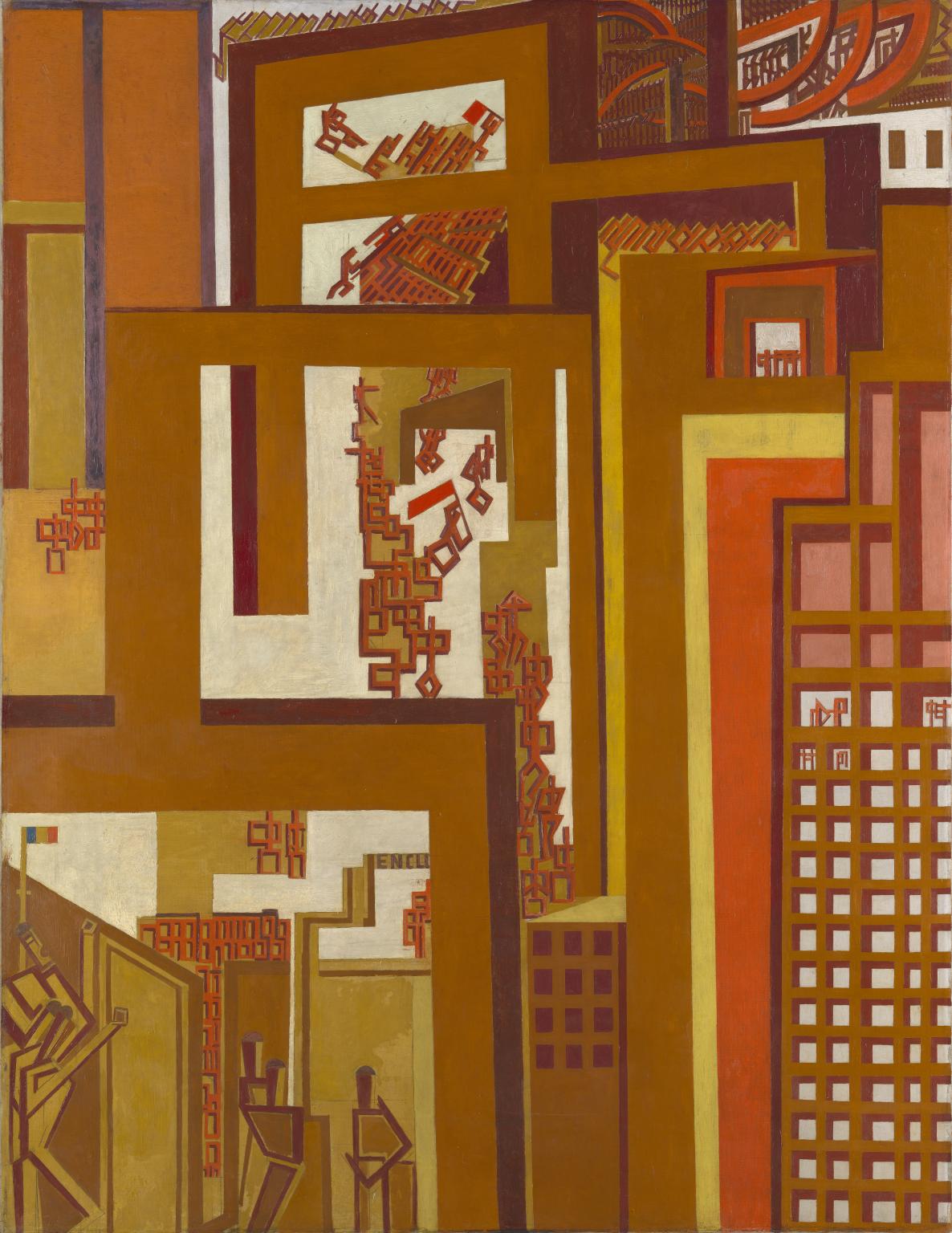

The Crowd (1915) is a visual portrayal of conformity and chaos, of individuals shattered by the city, which had been explored in Edgar Poe’s “The Man in the Crowd” (1840) and Gustave le Bon’s The Crowd (1895). It would later form the subject of David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd (1950) and Elias Canetti’s Crowds and Power (1960). King writes that in “the abstract painting created by the [red and brown] bricks and bands, the viewer sees human beings reduced to mechanized robots imprisoned within grids.”

The Crowd, 1915, Wyndham Lewis

The name Praxitella (1921) is a feminine version of Praxiteles, the ancient Greek sculptor. The powerful seated woman, modeled by Lewis’ longtime lover Iris Barry, appears off-centre on the right side of the picture and faces the spectator. She has a high, black, Japanese-style hairdo; a metallic, sharply angled, mask-like, dark-grey face; deep-set, heavy-lidded eyes; bright red lips; and pillar-like neck. Her robotic metal hands and bent fingers rest uneasily on the lap of her billowing black gown, bordered by wavy brown stripes. This scary monumental woman suggests unearthly power.

A Battery Shelled (1919), one of Lewis’ works as a Canadian War Artist, portrays on the left three standing officers: one of them smoking a pipe, another facing the viewer, with a moustache and modelled on Edward Wadsworth. The men seem to contemplate the ravaged wartime landscape with unnatural tranquillity and indifference. On the right and in the center, bent robotic stick figures flee for their lives under a barrage of artillery shells and smoke, and rush across a churned up and wavy oceanic battlefield.

A Battery Shelled (1919)by Wyndham Lewis.

The 22-year-old Gaudier’s dazzling portrait of his sometime Polish lover Sophie Brzeska (1913) is not, as King says, “motherly”. Portrayed bust-length and reclining, with an idealised profile, she rests her head on a large orange cushion decorated with floating leaves. She has black hair; an unreal, almost morbid, grey-and-blue streaked face; graceful nose, wavy lips and firm jutting chin. She wears a black shawl and loud-checked blouse layered over a dark blue dress. The 41-year-old woman seems dreamy but is forceful and attractive.

Like Edward Wadsworth, W. H. Auden was also perversely attached to the ugly and polluted industrial landscape of his native Yorkshire: “Tramlines and slagheaps, pieces of machinery, / That was, and still is, my ideal scenery.” Wadsworth’s masterpiece portrays complex, black-and-white, zebra-striped geometric patterns that camouflage the huge Dazzle-Ships in Drydock at Liverpool (1919). Tied to a bollard on the dock, surrounded and crowded by high industrial storage tanks and several smoking factories, the ship is ready to enter the sea and evade the enemy. Four tiny men, who emphasize the great height of the vessel and whose sleeves echo the dazzle designs on the ship and shore, use brushes on long poles to paint the rust-coloured hull and erase the old peacetime name.

Edward Wadsworth: Dazzleships in Dry Dock at Liverpool. (1919)

King weakly writes that William Roberts’ The Toe Dancer (not dancing on his toes like a ballerina) “demonstrates the artist’s mixed feelings about abstraction versus representation”. The naked acrobat performs on a stage with grooved parallel lines that descend toward the spectator. In the center the dancer with a metallic body, elongated legs and short bent torso, throws his right leg backwards to balance himself, extends his sharp-pointed fingers outward and gives the impression of dramatic energy. In the background a man seated at a large white piano provides the music. The figure in the top right imitates the frantic movements of the dancer. The 12 people in the audience are seated on narrow benches placed on a tight stage, and face each other in two parallel rows. One figure wears a nun’s cowl, the others are looking, chatting, snoozing, sleeping or embracing one of the women.

William Roberts’ stylized, nostalgic painting The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel: Spring 1915 (1962), recaptures the solemn festivity of the painters in Lewis’ favourite dining place, which he had decorated. In the right background a Vorticist painting portrays an athletic, muscular boxer, rope-jumper and weight-lifter. The large figure of Lewis at the center of the painting—wearing a heavy overcoat, red scarf and wide black sombrero, and holding a glass of champagne—dominates the group. He is surrounded by Pound, cross-legged, gazing upward and with a high staircase of red hair; and by the artists Cuthbert Hamilton, the boyish Roberts (aged 17), Etchells and the tall, bald, grey-skinned Wadsworth. They are all absorbed in conversation and ignore the late entrance of Saunders and Dismoor who hurry through the left-rear door.

Saunders, with thick black hair, waves a nervous greeting; Dismorr, with parted blond hair and determined expression, clutches her copy of BLAST. The proprietor Rudolf Stulik, who has a heavy mustache and an appropriately bulging stomach, offers a slice of Viennese cake topped with marzipan. Joe, the bald waiter, serves the ladies champagne to celebrate the publication of the brightly coloured BLAST. One copy of the “puce monster” rests on the white tablecloth under Roberts’ hands while another, prominently displayed by Etchells, shows the thick black capitals running diagonally across the lucent pink cover.

Jeffrey Meyers has published The Enemy: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis and Wyndham Lewis: A Revaluation (both 1980).

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.