Who in our time can replace Melvyn Bragg?

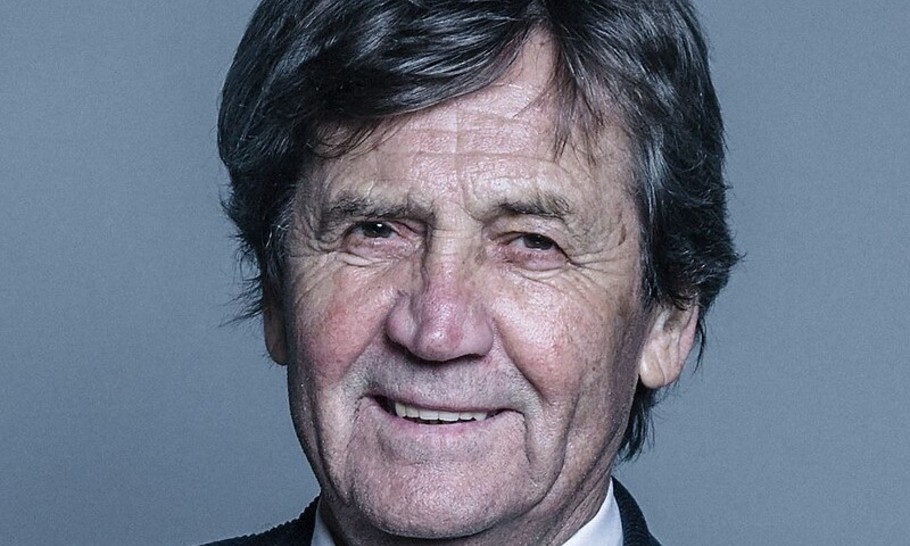

Official portrait of Lord Bragg by Chris McAndrew

When Russell Harty died in 1988, the BBC tried out several presenters to succeed him on Start the Week, including Kate Adie, Sue Lawley, George Melly and Melvyn Bragg. Fortunately, the new Controller of Radio 4, appointed in 1986, was Michael Green and he chose Melvyn Bragg, then in his late forties.

Bragg turned out to be a superb choice. He had made his name working on such famous arts programmes as Monitor, Read All About It and, of course, ITV’s The South Bank Show. But at Start The Week, where I first worked with him in the mid-1990s, he showed that he had an extraordinary range of interests and was at home with guests as different as the philosopher Bernard Williams, the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips and the American historian Robert Darnton, as well as leading figures from the arts such as David Hockney, Harold Pinter and the conductor Peter Sellars. The programme became very different from the days of Russell Harty. It had more intellectual gravitas yet its ratings increased to close on half a million.

Then in 1998 Bragg was elevated to the House of Lords and because he was a prominent supporter of the Labour Party it was felt by the BBC that he should not present a prime time programme on Radio 4 that covered current affairs as well as culture. Once again, Radio 4 was looking for a new presenter and over almost thirty years they have tried Jeremy Paxman, Andrew Marr, Tom Sutcliffe, Kirsty Wark, Adam Rutherford and Amol Rajan. None have been as successful in the job as Bragg.

Bragg, in the meantime, became the first presenter of In Our Time, also on Radio 4. It has been a huge success. The biggest difference between Start the Week under Melvyn Bragg and In Our Time, is that Start the Week consisted of discussions with a wide range of guests, many of them well-known figures, discussing a wide range of subjects, often promoting new books, films or plays, while In Our Time usually features three academic specialists discussing a single subject over forty-five minutes, from Einstein and Jupiter to Oedipus Rex, Louis XIV and Walt Whitman. The 1000th episode was about Ingmar Bergman’s most famous film, The Seventh Seal. Many guests have appeared several times, including the Dickens specialist John Bowen from York, the 19th century historian Lawrence Goldman, the Astronomer Royal, Lord (Martin) Rees and the Cambridge classicist, Professor Paul Cartledge.

When Bragg started at In Our Time, he told The Guardian, he gave it about six months. He recalled: “We were asking top-class academics to talk at the top of their form about a single subject – no book plugs allowed.” In the twenty-five years since it started, Bragg has established the programme as perhaps the best programme on Radio 4, or indeed on British radio. Just as important, he has confirmed his own reputation as one of the greatest broadcasters of our time.

Once again, the challenge facing the BBC is how to replace Melvyn Bragg. Writing in Unherd, Giles Fraser suggested Amol Rajan or Mary Beard. The Independent’s suggested shortlist is more wide-ranging. It included Amol Rajan, Samira Ahmed (Newswatch, Front Row), the historian Tom Holland, Ben Ansell (a politics professor at Oxford and presenter of Radio 4’s Rethink series) and Jonathan Freedland, all with significant presenting experience on Radio 4. According to The Times, the BBC was interested in recruiting Mishal Husain for the job until she decamped to Bloomberg.

In the past, Radio 4 has always been torn between big names and media personalities like Jeremy Paxman, Andrew Marr, Kirsty Wark and now Freedland, Amol Rajan, Tom Holland, Mishal Husain or Mary Beard. One can obviously see the temptation. They are all smart, with the breadth of interests that Denis Healey called a “hinterland”.

Above all, there is much to be said for going against the BBC conventional wisdom. Some of Bragg’s successors at Start the Week were too middlebrow, too many journalists or presenters from current affairs. That’s why our newspapers have predictably got it wrong as well. They have forgotten the USP of In Our Time. To everyone’s surprise it was a success, not because it was middlebrow, but because it wasn’t. Like Bragg himself, it was unashamedly highbrow, refusing to go downmarket. Look at the topics covered and the choice of guests. Bragg has always championed the right of viewers and listeners to be introduced to the very best culture has to offer, whether in the arts, sciences or the humanities.

In Our Time should continue with this legacy. When I suggested Michael Ignatieff would be an excellent presenter for Channel 4’s discussion programme, Voices, I was impressed by his youth but also by his range of interests. I was not surprised when after two series he left to replace Bryan Magee at BBC 2’s Thinking Allowed. Magee was supremely articulate, famous for presenting intellectual BBC2 series like Men of Ideas and The Great Philosophers. Ignatieff was just as articulate but he was younger, more handsome and had a transatlantic accent which attracted him to the producer of Thinking Allowed and then Michael Jackson, the founding editor of The Late Show, where Ignatieff was one of the presenters from 1991-95.

When the BBC was looking for presenters to front an updated version of Civilisation, they thought Kenneth Clark, who presented the original series in the 1960s, was too white, too male and too posh. So they went with three presenters instead of one: Simon Schama, Mary Beard and David Olusoga. It was disastrous. They forgot, above all, that this wasn’t about ticking boxes. It was about how much people knew. Clark, like Bronowski and Bragg, knew a lot and was terrific at talking about it to large audiences.

Bragg chaired discussions on In Our Time that ranged from 19th century slave uprisings such as the Morant Bay Rebellion to the films of Fritz Lang, or from ancient historians to John Donne and Rawls’ theory of justice. He would never claim to be an expert in any of these subjects. But he was passionately interested in all of them and believed that his audience could also find such subjects interesting and deserved not to be spoken down to.

I know some of the people on The Independent’s list and I like them all. They are all clever people, very articulate. But would I really want to hear them talking to a group of specialist academics about Gödel’s incompleteness theorems or Cicero? Are they curious enough about enough subjects? Do they have a sense of the BBC audience in their bones in the way Bragg has?

Ticking boxes is not enough. Knowing about politics or having the experience of presenting another Radio 4 programme are not enough either. It’s not about how much you know, but how much you want to know that makes an outstanding presenter of this kind. The BBC has a terrible record of getting many of these appointments wrong. Not always, of course. John Wilson (This Cultural Life), Jim Al-Khalili (The Life Scientific), Matthew Sweet (Sound of Cinema), Jay Rayner (The Kitchen Cabinet) and of course, Melvyn Bragg, are among the wonderful exceptions. I hope this time, the BBC will cast their net wide and surprise us all.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.