Phoenix rising: Tamara de Lempicka

Tamara de Lempicka, Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti)

Gioia Mori and Furio Rinaldi’s Tamara de Lempicka (exhibition catalogue at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, October 12, 2024 to February 9, 2025, Yale UP) presents an exciting woman painter whose work far transcends her limited Art Deco label. With technical brilliance, vibrant colors, shining hard-edged surfaces and elegant realism, she has finally achieved the great reputation she deserves.

Like a high-fashion model, a Hollywood film star and a theatrical grande dame —as critical, imperious and demanding as Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard —Tamara created her own myth. Multi-lingual and cosmopolitan, beautiful, bisexual and promiscuous, she was especially fond of men who loved both sexes. She had a lavish way of life, indulged in relentless self-promotion, and constantly pursued high society in Europe and America in search of rich patrons and portrait commissions. She even painted Rufus T. Bush, who sounds like a character in a Marx Brothers movie.

Polish and Jewish, she was born Tamara Gorsa-Hurwitz in Warsaw in 1894 and named after the romantic heroines of Mikhail Lermontov’s poems: “ A prey to voluptuous longing, / Tamara awaited her guest.” She lived in St. Petersburg, fled the Russian Revolution, and then restlessly moved between France, Italy, America and Mexico. She was unfaithfully married to the handsome Tadeusz Lempicka from 1916 to 1928. But “he felt neglected by his wife’s work and success, humiliated by her affairs, and fed up with her eccentricities, including her abuse of cocaine and habit of painting with Richard Wagner’s music played at full volume”.

In 1916 they had a daughter, Marie-Christine, called Kizette, a childhood variant of her second name. Educated at Oxford and Stanford, Kizette married an American geologist and lived in Houston, Texas, where Tamara was a frequent but unwelcome and oppressive guest. Tamara married Baron Raoul Kuffner in 1934 and remained with him until his death, on a transatlantic liner, in 1960. In 1980 she died in Cuernavaca, the violent setting of Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano , and had her ashes spread by helicopter on top of the Popocatépetl volcano portrayed in the novel.

Tamara was both original and traditional, and her portraits have the clarity of the Old Masters. Wisdom (1940) was modeled on Van Eyck’s Portrait of a Man (1433), wearing a high and elaborately curved and twisted red turban. In 1930 she painted a portrait based on Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s orgasmic statue The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1652). She was also influenced by the models, colour, style and smooth surface, by the grace, elegance and dramatically elongated figures of the Mannerists: Pontormo’s Venus and Cupid (1533) on her entwined erotic nudes and Bronzino’s Portrait of a Young Man (1531) on her Woman with Green Glove (1928) with her seductive contrapposto stance and hand on hip.

‘Woman with a Green Glove’ by Tamara de Lempicka (1928)

Tamara painted a close-up of the defiantly homosexual author, Portrait of André Gide (1925), when he was 56. He has dark skin, bald head touching the top of the frame, dangling grey hair, heavy eyebrows, black almond-shaped Modigliani-eyes with no iris, lined cheeks, masklike face shadowed on the left and an anguished expression. The portrait is now owned by the actor Jack Nicholson.

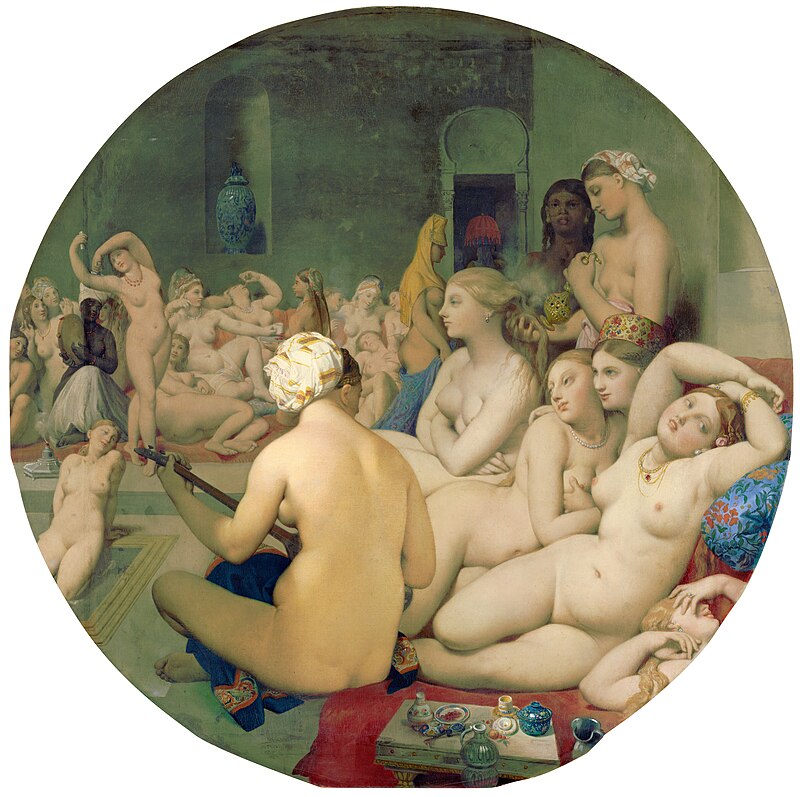

The Four Nudes (1925) further roticizes the smooth and polished finish of J.A.D. Ingres’ orgiastic assembly of curvaceous bodies in The Turkish Bath (1862). Her painting is a naked modern version of the 1880s photo in Laura Claridge’s biography of Tamara’s mother and three aunts. They sit in two rows, form a square touching each other, and have pale faces, fluffy black dresses and high hair. The sexually entangled bodies of Tamara’s Four Nudes have their arms thrown back behind tilted heads to lift their prominent breasts, faces with closed blue eyelids and open red-painted mouths. They have erect nipples, large bellies, spread legs, mossy pubic hair. Their smooth skin cries out for a caress and they experience orgasmic ecstasy. The fourth woman, hair sharply parted in the middle, wide open almond-shaped eyes and stern expression, looks down on the sullen alluring faces swooning in voluptuous abandon. Tamara’s models were sometimes prostitutes and often her lovers. Uncorseted, the ample busts gave promise of pneumatic bliss.

The Turkish Bath (Le Bain turc) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique (1862)

Grand Duke Gavriil Romanov (1927) portrays a cousin of the czar. The unfortunate duke was arrested and imprisoned by the Soviet Cheka in 1918 but, infected with tuberculosis, was freed through the intervention of the writer Maxim Gorky. Gavriil fled to a sanatorium in Finland, then to exile in Paris. In this half-length portrait, he’s very tall, with a long head, high forehead, blue eyes, strong nose, full lips and gloved hands. Stiff-necked and high-collared, he wears the red-and-gold dress-uniform of the Russian Imperial Guard with belled tassels hanging from his belt. His epaulettes emphasise his broad shoulders, and he is lashed with a sash, by decorative cords and cables around his chest that seem to bind him like a captured animal. He turns to the left with a pale face “marked by illness, lost rank and melancholy exile”. Hurt by history and fallen from high estate, he could say with James Joyce’s Leopold Bloom: “Me. And me now.”

The Portrait of Tadeusz Lempicki (1928) depicts Tamara’s dashing first husband. His broad white forehead and handsome half-shadowed face is tilted to the left. The tall figure wears a thick white silk scarf under his long heavy, double-breasted, sharp-lapeled coat. His grey-gloved left hand holds a shiny top hat, and the curled fingers of his pale right hand look like steel claws. He has dark hair, dark eyebrows, dark cheeks, dark folds in his scarf, dark coat, dark buttons and dark top hat. Standing before a background of tall silver pillars and buildings perforated by windows, he seems aggressive, menacing and sinister. There’s no hint of tenderness or affection in this severe portrait.

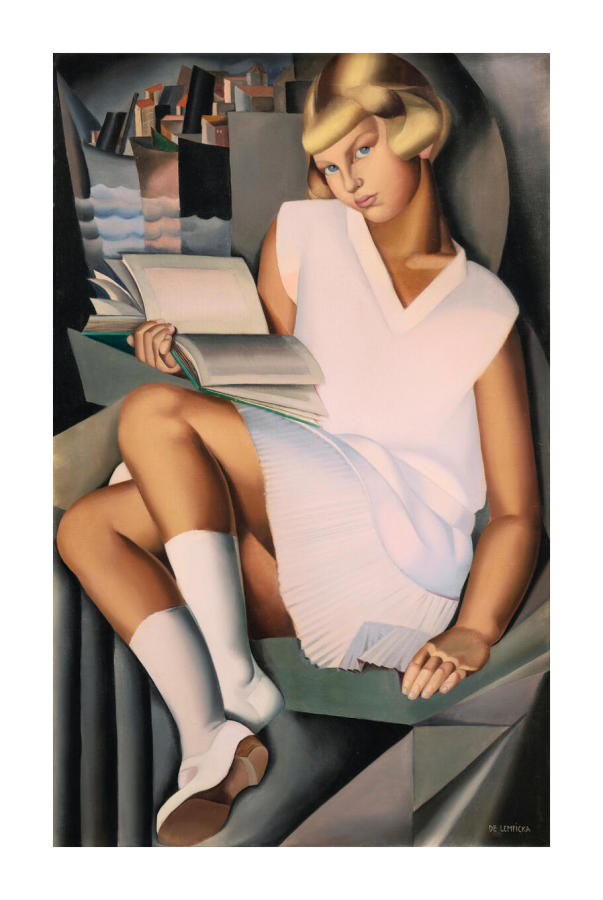

In Tamara’s masterpiece, Young Girl in Pink (1928), her 12-year-old daughter and model Kizette has a helmet of wavy blond hair and bright blue eyes, and is holding an open book. The harsh geometry of tilted Manhattan skyscrapers and ships in jagged waves behind her contrast with her soft flesh. She crosses her ankles, and wears a V-neck blouse, high white socks, white Mary Jane-shoes with a crossed strap. Her head is turned to the left and her pretty face with parted lips has a seductive look of virginal depravity. Like Balthus’ nymphets and Nabokov’s Lolita, she reveals her upper thighs beneath her tennis skirt, whose pleats are echoed by her fingers. She seems more prepared for breeding than for reading, for sexual adventures rather than for sport.

Tamara de Lempicka, Young Girl in Pink (Kizette in Pink II), ca. 1928–1929

The Portrait of Baron Raoul Kuffner (1932), Tamara’s Hungarian second husband and gentle contrast to Tadeusz, does not suggest that he was a hunter of fierce Alaskan bears in real life. He has an expressive soft face, V-shaped tuft of hair on his forehead, neatly trimmed grey moustache, shadowed eyes swiveled to the left and head supported by a stiff white collar.

The elegant and imperious contrapposto figure of the 53-year-old French bacteriologist in the Portrait of Doctor Pierre Boucard (1928) cuts diagonally cross the picture. His head looks left, his torso faces straight ahead, his leg moves to the right. He has a grey streak in his dark hair, high tanned forehead, heavy eyebrows, long nose, sharply trimmed split moustache, thin lips and pensive expression. A blue silk tie beneath his stiff collar is punctured by a pearl pin. He wears a long sharply-cut silver-grey long-belted overcoat over plain brown trousers. His left hand rests on a gleaming gold multi-ocular microscope. Boucard’s right hand holds a tilted cotton-topped test tube that suggests a bloody urine sample and hints at a mad scientist doing dangerous experiments. The tube actually contains a sample of his patent medicine Lactéol, which he discovered in 1907 (and is still being sold) to cure diarrhea and digestive problems. It made him a millionaire: he wore expensive suits and owned a Rolls Royce.

Portrait Of Dr. Boucard, 1929 – Tamara de Lempicka

In Tamara in Green Bugatti (1929), an auto-erotic self-portrait, her initials appear in a tiny black frame above the door handle. She has heavy eyelids, full red lips and a sullen expression. Adorned with a grey helmeted aviator’s hat and chin-strap, from which a blond curl emerges, she is swaddled in a windblown grey cape. She sits behind the raised windshield of the metallic yet sensual racing car, which had 140 horsepower and could reach 122 miles per hour, grips the black steering wheel with her leather-gauntleted hand and speeds toward an unknown but thrilling destination.

Tamara de Lempicka, Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti)

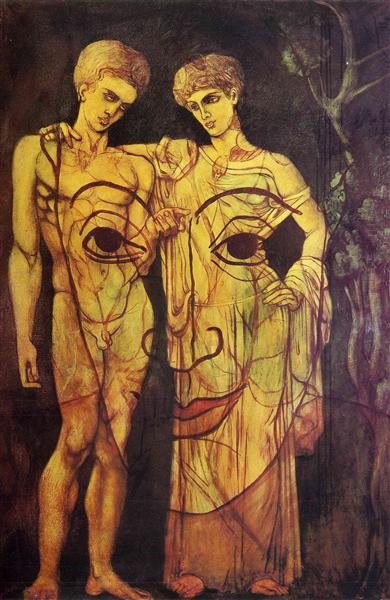

In Adam and Eve (1931) a rare male model is seen from the back with his dark helmet of hair cut off by the top of the frame. He’s very muscular, with curvy spine, apple-like buttocks and long legs. His half-shadowed head is bent down and touches Eve’s head. She has blond hair curled like steel rings, long pale nose, full red lips, soft belly and generous display of pubic hair. Her body faces the viewer as she turns her profile away from Adam and clutches an apple with her nail-polished fingers. Adam’s right arm embraces Eve’s body under her left breast, whose nipple is erect as a soldier on parade. There’s no Tree of Knowledge or devilish snake, so their sinless, possibly stand-up sex, could take place before she eats the fatal apple. The skyscrapers in the background place the nude couple in the modern era. Barbra Streisand bought this painting for $135,000 in 1984 and sold it for almost two million dollars a decade later.

Adam and Eve, c.1931 – Francis Picabia

Tamara made a lot of money from her art and gave lavish parties for hundreds of guests. During one of her lubricious festivities she plastered food all over the naked bodies of nubile women and encouraged the guests to lick it off. She had fascinating, tempestuous and detumescent relations with the Italian writer and war hero Gabriele D’Annunzio.

Laura Claridge writes that Tamara visited him at his splendid palace Il Vittoriale twice between December 1926 and February 1927, but “trapped by his insistence that she sleep with him, she fled in the middle of the night”. D’Annunzio tried to impress her by flying her over Lake Garda in his private plane and by bribing her with cocaine but, playing the coy virgin, she stubbornly refused to become another sexual trophy of this remarkably ugly man. She was flattered by his pursuit and determined to paint his portrait but, fearing that sex with him might make her pregnant or infect her with syphilis, she continued to resist his assaults. “She allowed him soulful kisses in the armpits and let him feel her body through her clothes.” But the famed cocksman—who according to one mistress had eyes like “little blobs of shit”—“was appalled that he could ejaculate against her only when she was fully dressed. As he was fully erect and about to penetrate her, she asked, ‘Why do you do such horrid things to me?’ His nonstop histrionics, including his habit of sleeping in his own coffin, offended her delicate sensibilities.”

Like the figurative painters Alex Colville, George Tooker and Philip Pearlstein, Tamara resisted the torrents of abstract art in Paris and the rage for Abstract Expressionism in New York, and continued to paint in the realistic tradition of great artists. The authors of this gorgeous volume conclude that Tamara has “a cerebral coldness juxtaposed with voluptuous tension . . . a combination of cool classicism, explicit eroticism and Sapphic audacity.” She inherited from Ingres the purity of line, the sculptural nudes, the few nuanced colours and the beautiful icy calm.

Despite endless travels, broken marriage, severed friendships, emotional convulsions, serious illness, deep depressions and harsh criticism, she continued to work and created 500 paintings, with especially fine portraits and nudes. In February 2020, forty years after Tamara’s death, her Portrait of Marjorie Ferry (1932) sold for $21.2 million.

Portrait of Marjorie Ferry, 1932 – Tamara de Lempicka

Jeffrey Meyers has published Painting and the Novel , The Enemy: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis , Impressionist Quartet , Modigliani: A Life and Alex Colville: The Mystery of the Real .

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.