Pierre Bonnard's true colours: a dazzling array from the master colourist

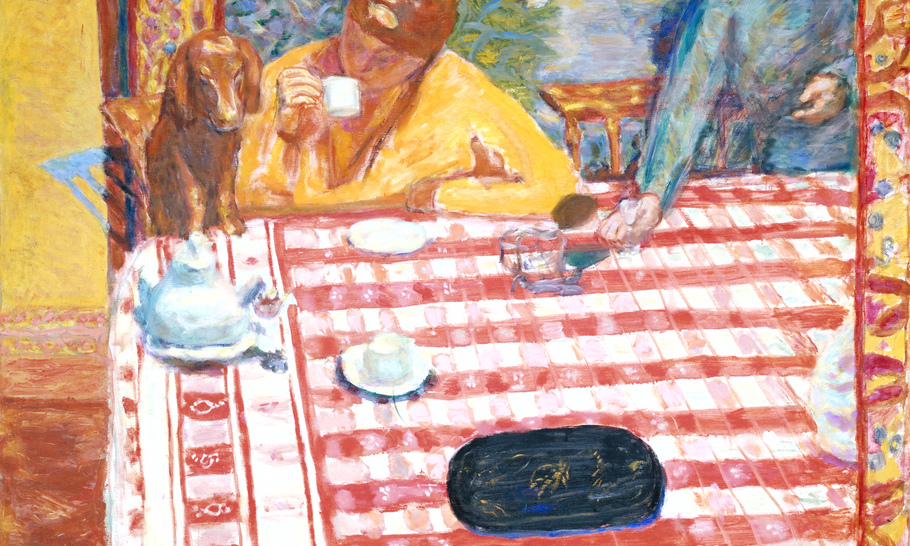

Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), Coffee (Le Café) 1915, Oil paint on canvas, 730 x 1064 mm

An oil on canvas from 1919 shows a woman wearing a long pink dress cinched at the waist. She is standing in a tastefully furnished room, her back to a window. Outside, beyond the balcony balustrade, a stretch of sea glistens. Inside, rays of sunshine bathe certain objects while leaving others shrouded in shade. The woman is carrying what is either a cup for herself or a bowl for the cat mooching around at her feet. Along the edge of a nearby tablecloth runs a word, as if neatly embroidered rather than carefully written. On closer inspection it is a name, a signature – ‘Bonnard’.

This captivating painting by the master colourist was originally exhibited in 1920 under the title Interior. Four years later it was expanded into Interior at Antibes. In 1937 it ended up as The Bowl of Milk. At first blush it looks straightforward enough – a tranquil setting, a woman and her pet – but then we notice that the milk in the bowl isn’t the only white feature. Our gaze is drawn to an equally pale band of light across the top part of the woman’s face which accentuates her nose and cheeks but leaves her eyes obscured. It is a curious effect: her closed lids are smudges, rendering her not only sightless but eyeless. We now look at the whole painting afresh and see the woman rigidly still, studiously impassive, frozen in time or locked in a trance.

This work, and others like it, is currently on show at Tate Modern in what is the first major exhibition of Pierre Bonnard’s work in the UK for 20 years. This time around, instead of a pick-and-mix retrospective of his whole career, the focus is on the art Bonnard (1867-1947) produced in the second half of his life, from the early twentieth century until his twilight years. This means none of the work influenced by Japonisme, nor the conversation pieces and urban scenes of fin-de-siècle Paris are exhibited here. What we get are over a hundred sumptuous, sensuous, colour-infused paintings – some of them of blooming, verdant landscapes, others of indoor activities and routines. With the latter, we see again and again many of the motifs from The Bowl of Milk: rooms with a view, domestic clutter, splashy sunlight, and all or part of a female figure – nearly always Marthe de Méligny, Bonnard’s muse and model, companion and later wife. As Julian Barnes has observed, Marthe becomes “part of the furniture”.

‘Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory’ makes for a fitting title as it yokes together the two aspects most associated with him. His love affair with colour began during an extended stay in the south of France in 1909. Awed and inspired by perfect blue skies, warm tones and transformative soft light, he went on to buy a hillside villa in Le Cannet, north of Cannes. There, and in his studio in Paris and his house in Normandy, Bonnard worked, and always from memory. “The presence of the object”, he remarked, “is a hindrance for the painter.” He made sketches, drawings and even photographs of his subjects and surroundings, jotted down the appropriate colours, and then created paintings from his rough drafts, gathered notes, salvaged recollections and primary sensations.

This singular modus operandi yielded unique results. Bonnard was his own man who did his own thing, an artistic outlier who belonged to neither impressionism nor fauvism. Consequently, he is hard to pin down and sum up. As his compositions are derived from acts of remembrance, reflection and re-interpretation, there is a stark prioritisation of moods, instincts, textures and bold colour over attempts at verisimilitude. In his indoor scenes, perspectives are warped: horizontal surfaces are presented at elevated angles; stationary objects appear off-kilter, out of sync with each other. Coffee (1915) shows this to good effect. A red and white checked tablecloth takes up most of the painting. On it, blurry cups, hazy glasses and a precariously balanced teapot defy gravity and stay put. Marthe, resplendent in yellow, sits across from us and sips from a cup held in her impossibly small hand.

Here, and elsewhere, Bonnard’s misleading titles try, unsuccessfully, to relegate his true focal points. Just as the tablecloth is the real centre of attention in Coffee, so too is a mirrored image of a naked Marthe in The Mantlepiece (1916) and the abundant trees and bushes in The Violet Fence (1923). In addition, Coffee is not the only painting in which people are cropped, downsized or shunted to the sidelines. In the commandingly huge Dining Room in the Country (1913) a marginalised Marthe sits outside looking in, secondary in size and importance to, of all things, an open door. The equally large Summer (1917) portrays a naked couple at one with nature, but also engulfed by it. Some works depict Bonnard’s subjects soaking up the colour of their environment – the hair and faces in Estérel (1917), for example, blend in with the sand on the beach; other paintings’ sitters vividly stand out, such as the vision in vermillion in Woman at a Table (1923). When people disappear completely we are often left with nature, both tamed and untamed, in a variety of forms and in joyful bursts of yellow, rich washes of orange and riotous swathes of green.

The exhibition is not all daily pursuits and sun-kissed exteriors. It includes several beguiling anomalies, not least A Village in Ruins near Ham (1917), a rare bleak snapshot of the carnage and futility of the First World War. Piazza del Popolo, Rome (1922) is just as much a black sheep: foreground women pose dutifully and stare right out at us. It looks too staged and contrived when set against the bulk of Bonnard’s output, which is so much about captured moments, stolen glances, fleeting instances – people caught mid-act or mid-gesture. We see this in his standing nudes, who go about their ablutions as if unaware of Bonnard’s roving eye, and also in his famous paintings of Marthe in the bath. The exhibition has arranged Bonnard’s work chronologically, which means those bath pictures, which Bonnard worked on over two decades, are not grouped together in a suite but scattered far and wide. Coming across another one, in another room, is a repeated pleasure. Perhaps the standout is Nude in the Bath from 1925. The bath tub, like the table in Coffee, looks as if it has been tilted upwards. Marthe’s lower body lies immersed and suspended. A partially revealed bath-robed figure, presumably Bonnard himself, enters from the left. The painting evokes mixed feelings. On the one hand it is a glimpse of a close and healthy relationship; on the other it shows a voyeuristic interloper intruding upon an exposed and vulnerable baigneuse.

“I float between intimism and decoration”, Bonnard declared. This stunning exhibition gives us the best of both worlds. However, it won’t be for everyone. Certain viewers may side with Picasso who accused Bonnard of producing “a potpourri of indecision”. His people can be puppet-like, even cartoonish, his cats and dogs not so much regurgitated from memory as cobbled together from guesswork. Above all, daring colour schemes for some are garish colour clashes for others. But the sceptics and detractors should look closely at the more complex works: those polarising bath scenes, busy tabletops, shaded dining rooms, and the searing and disturbing self-portraits composed at various life-stages, collectively chart the artist’s gradual decline from hale and hearty to bowed and broken. The sun doesn’t shine in these pictures but we are still dazzled by a glow.

Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory is exhibited at Tate Modern, London until 6 May.