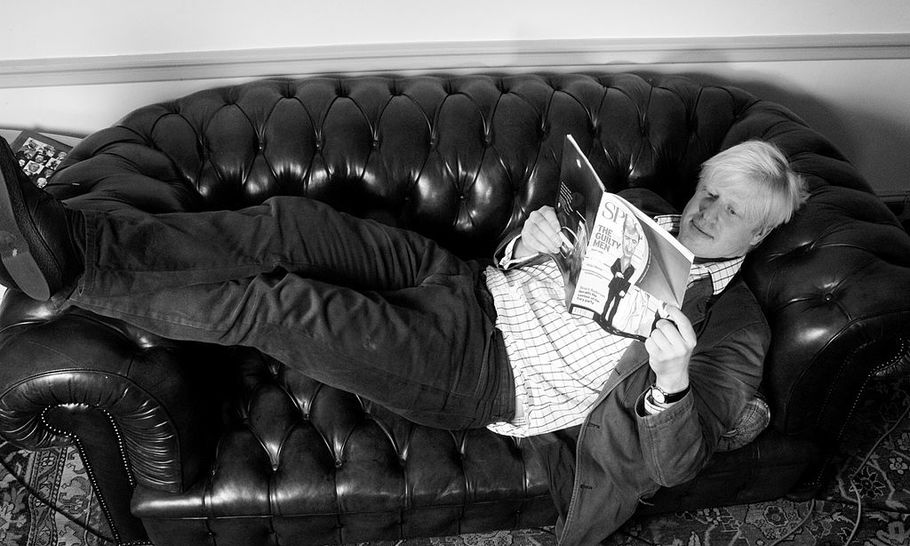

The self-interested man

(Photo by Cambridge Jones/Getty Images)

I’ve been watching politicians for around 20 years now and I have come to realise that they are driven on by two competing instincts: on the one hand there is self-interest and on the other, the urge to serve. It’s a distinction that cuts across the left-right divide. A Conservative might feel an instinct to serve Queen and country, just as a more left wing politician might be motivated by the idea of of serving one’s community, especially the vulnerable. Others might be a combination of both instincts.

On the other side, there is self-interest — all politicians have it. You can’t win selection rounds, constituency battles and General Elections without it. Some have more self-interest, and others less, but it is there all the same. Self-interest and service are side-by-side in every politician and always in tension, as the urge to serve oneself pulls one way and the urge to serve others pulls another. The problem comes when one of these instincts gets out of hand.

Corbyn was the classic example of a politician who was all “service” and no “self-interest”. Politicians can’t operate like that, especially not if they’re the leader of a political party. When it comes down to it, people don’t want a servant running the country — they want a leader. But in everything Corbyn did and said, he thought and spoke exclusively in terms of giving assistance, of interceding on behalf of those who couldn’t do it for themselves. It was no coincidence that his best friend and political companion John McDonnell had once trained to become a Catholic priest. Their instincts were complimentary.

Corbyn’s problem was that he had no self-interest. If he had, then perhaps he might have thought less about signaling his depth of feeling for the less-well-off both in Britain and abroad, and spent more time trying to win a General Election. But his chronic shortage of self-interest meant he wasn’t up to it.

For Corbyn, a man of the hard left, self-interest is a dangerous idea. It sounds too much like competition, like something to do with the market economy. This is yet another of the awkward little contradictions that the left has always faced — it has to compete electorally in a political fight that looks uneasily like a marketplace and which demands the instincts of a market participant for victory. Self-interest is a necessary condition for political victory, a fact that Blair understood — Brown less so. Miliband didn’t, and it was his puritanical gesture in opening up party membership that led straight to Corbyn and to a defeat of historic proportions.

Corbyn, a man who showed almost no signs of self-interest, ended up losing a General Election to a politician who is made of nothing else. Boris Johnson is Corbyn’s political opposite. Where Corbyn was happy to sink to the bottom with his principles tied firmly round his neck, Johnson is free of any such burden. He floats, buoyed up by a willingness to do and say anything, so long as it sustains his mission of self-promotion.

The story of Johnson and the two contradictory newspaper articles on Brexit is the clearest expression imaginable of his weapons-grade degree of self-interest. On the eve of the campaign, he wrote one article extolling the virtues of the EU and throwing his weight behind the Remain campaign, and another version in which he excoriated Brussels and committed himself to the Leave cause. He then decided which one would be more advantageous for him personally — and filed accordingly.

Absent from Johnson’s calculation was any sense that he was thinking about what might be best for other people, for the country, even. There was no sense of service in what he did, no consideration of others — just as there was no sense that he was thinking about his former wife when he divorced her while she was suffering from cancer, or when he fathered a child for whom he then failed to take responsibility, or when he invented quotes as a journalist and so on and so on.

Johnson is almost pathologically self-interested, a characteristic that is captured perfectly in what is supposedly a favourite motto: “never apologise, never explain”. It was this unsavoury ethic which meant that Dominic Cummings, Johnson’s number two, despite breaking the lockdown rules that he himself had helped to create, was not fired or even censured by the Prime Minister. Instead Cummings held one of the most disgraceful press conferences in living memory, in which he revealed himself to be the pure distillation of the Johnsonian Number 10. Lies, evasions and absurd excuses are all fine, so long as enough fog is put up to keep you in the job. In the end, with Cummings, that is what happened.

But now we have an even greater absurdity. The government argued for the EU Withdrawal Agreement, fought a General Election on the back of the Withdrawal Agreement and held up the Withdrawal Agreement as a triumph for Britain — and it is now attacking the Withdrawal Agreement. It’s a staggering piece of political brazenness, all the more so in that No10 seems to think the public will swallow it.

But we should not be surprised by this. The purely self-interested man, or woman, will do and say anything to achieve their ends. There are no boundaries, there is no honour, no sense of higher purpose. That’s how Brandon Lewis, a Government Minister could stand up in the Commons and announce that, in relation to the Withdrawal Agreement, the government now intended to break international law in a “selective and limited way”. Did Lewis even understand what he was saying, what he was giving away with those words?

Johnson certainly doesn’t seem to care. Lewis’s words don’t appear to have been a mistake. There has been no retraction, or clarification, only the sound of heels digging in. Which raises the question of what Johnson actually wants. To get Brexit done? Perhaps. But if so, why sabotage his own Brexit deal? Perhaps he wants to force a no deal. But if so, why not simply admit it, thank Michel Barnier for his time, end the negotiations with the EU and have done with it? Or perhaps he wants no deal, but also wants to pass blame for it onto the EU. But then the “passing the blame” bit of that explanation is a tacit admission that he knows a no deal Brexit would be a disaster for which he wants to avoid responsibility. If he knows it will be a disaster, why go for no deal at all?

The self-interested person tends to be one who sees him- or herself as deserving of special treatment. The rules don’t quite apply to them and so yes, it is fine to sign an international treaty with great fanfare and a few months later to condemn it as a stitch-up. But it is unnerving to see how Johnson’s character is colouring the character of Britain itself. The petulant expectation that Boris should have whatever Boris wants whenever Boris wants it is now our negotiating position with the EU. This brings with it the troubling sense that, as far as the outside world is concerned, his character is becoming our character.

Britain is stuck in a slough of self-interest, held down by the enormous weight of Johnson’s ego. His plans are a mess. Britain’s economy is weak and our mortality rate from Covid is one of the highest in the world. The EU and US are both appalled by the government’s blasé dismissal of international law. But none of that matters to Boris. For him it’s all about being in charge and other people giving him what he wants — his own imbalanced character means he can’t see things in any other way.

It’s a shame for him that the EU doesn’t see it that way. For the rest of us, it’s nothing short of a catastrophe.