Splinter of ice: the letters of John le Carré

(Shutterstock)

A Private Spy: The Letters of John le Carré Ed. Tim Cornwell. NY: Viking, 2022.

713 pp. $40.

I

John le Carré (born David Cornwell) had a galaxy of extraordinary qualities. Though cursed with a criminal father, he was handsome, intelligent and earned a First in modern languages at Oxford. Downhill skier, gifted illustrator and brilliant linguist, he was a devoted father of four sons, loyal friend, genial host and generous benefactor. After a career as a secret service agent in Vienna, Bonn and Hamburg, he transformed the spy thriller into serious literature.

Le Carré (1931-2020) moved restlessly between his three homes: in Hampstead; Cornwall, his substitute for exile; and his ski chalet in the Bernese Oberland, where he took “refuge from an increasingly rackety world.” He also went on frequent research trips, to consult experts for the details and background of his novels, from Germany to the Congo and South Africa, from Russia to Panama and Southeast Asia. Alert to the current political strife, he described how he worked on a novel: “I seem to do nothing but fly round the world in aeroplanes to write the new book. . . . I’m in search of colour & locations & first hand knowledge of the local tensions.”

A compulsive writer (and dyslexic reader), depressed by “after-book,” he felt “the time drags awfully when I’m not working” and wanted to die with a pen in his hand. He was always thinking of something new, of devising (for example) a story about the rise of new dictatorships in “the bloodlands of Eastern Europe.” He began with two or three characters awaiting development, wrote fast and revised extensively. He didn’t “care to spend too long on a book—the paint gets thick and grey and the subject changes too often.”

Le Carré would have been pleased with this edition of his Letters — though not, perhaps, that they have already been published in the US but will not appear for another six months in his native Britain. The photographs are well chosen; the index complete; the introduction, background, footnotes and chronology by his third son (who died, age 59, in June 2022) are excellent: expert, accurate and incisive. The print is easy to read and the heavy volume stays flat when opened.

Le Carré’s parents cast a long shadow in this book. His mother deserted her two sons and escaped with her lover when le Carré was five years old. When he met her seventeen years later and for the first time in his adult life, he was disgusted by her shameless assumption of “an idyllic mother-son relationship that had flowed uninterrupted from my birth till now”. The themes of abandonment and search for love recur throughout his life and works.

His charismatic con-man father, Ronnie Cornwell, beat up and infected le Carré’s pregnant mother with syphilis. He had three wives and several children, molested his son, shared a bed with a wife and mistress, and was brutal and unfaithful to all his women. Le Carré and his older brother lived like millionaires when Ronnie’s fraudulent plots paid off, but the less he had the more he spent. At one time he bought racehorses and ran for Parliament; formed 60 companies, bought 4,000 properties and accumulated spectacular debts of £1,359,000 (about £100 million today). Many victims, including family members, were financially crippled in Ronnie’s fearful wake. When seedy and on his uppers, he even turned a few pennies by signing le Carré’s books “from the author’s father.” Ronnie’s friends were sinister, his associates violent, and on several occasions he was caught and convicted. The boys were reduced to paupers when their school fees were paid with worthless cheques, and the charming deceiver was imprisoned in Exeter, London’s Wormwood Scrubs, Zurich, Hong Kong, and Djakarta for arms smuggling. (Like the Italian patriot Silvio Pellico, Ronnie could have written My Prisons.)

Ronnie, who’d coerced and corrupted le Carré in his schemes, had trained him from childhood to lie, deceive and betray, to have a hidden life of outward conformity and inner rebellion. Ronnie’s scandals shamed le Carré as a schoolboy and adult, and he told his brother, “Our father was a mad genes-bank, a truly wild card, and in my memory disgusting—still. I never mourned him, never missed him, I rejoiced at his death.” Yet in some perverse way, he needed the paternal wound to transform himself from David Cornwell into John le Carré. As Auden wrote in his elegy of Yeats, “Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry.”

Apologising to his family for defects of character, le Carré (with more than a touch of self-pity) blamed his parents: “I had no learning in parental love, no trust in women, no identity beyond a terrible need to escape my vile childhood & be acknowledged in some way.” He’s had “such an awful life in so many ways, and looks so terribly impressive from the outside. But the inside has been such a ferment of buried anger and lovelessness from childhood that it was sometimes almost uncontainable.” He gave his fictional character George Smiley some of his own qualities and noted his solitude, humanity, high principles and perception of human frailty. But Smiley is also “a guilty man, as all men are who do, who insist on action.” The great theme of his novels is moral conflict, expressed with moral anger.

Le Carré hated Sherborne, his school in Dorset. At Lincoln College, Oxford, he specialised in obscure 17th-century German writers and felt close only to Goethe, Heinrich von Kleist and Georg Büchner. He doesn’t mention the great modern authors: Rainier Maria Rilke, Robert Musil and Franz Kafka. He is silent about Thomas Mann’s Felix Krull, Confidence Man, which had personal and professional significance, and about Joseph Conrad’s influential The Secret Agent and Lord Jim’s dishonourable behaviour and quest for redemption. He calls the brilliant movie Mephisto, based on the novel by Klaus Mann and starring Klaus Maria Brandauer, “the greatest film of my life.” His favourite authors were Charles Dickens and P. G. Wodehouse; and he particularly regretted missing the chance to meet Wodehouse, Noël Coward and the adventurous Polish writer Ryszard Kapuscinski.

Le Carré taught German and French at Eton, where he loathed the prevailing arrogance, the disdain for middle and lower-class “oiks,” and the belief that the sexual “needs of the ‘bloods’ must be served by the smaller boys.” He also hated and feared Russia, a country “responsible for some of the most brutal, conspiratorial, murderous and unprincipled régimes the world has seen . . . that can’t face its past, its present or its future without a shudder.” He called contemporary Russia “a kind of Czarist Wild West, but tortured by guilt, religion, laziness, and its own unbelievable waste of talent”—or what was left of it. At least in the old days, he said, you knew who the crooks were—and there were no oligarchs and billionaires.

While training as a spy, le Carré satirically recalled, “we played with radios, codes, secret inks, knives and hand guns . . . [explored] the minds of traitors, grappled with each other in unarmed combat, and undertook mock operations in strange towns.”

He believed that the East German spymaster Markus Wolf “served a disgusting regime in disgusting ways and knew exactly what he was doing”. Le Carré, by contrast, felt he had patriotically served as a spy to protect his own country and had fought the Cold War “for the dignity and protection of minorities and small nations in the face of totalitarian action,” a belief especially relevant to us during the current Ukraine war.

While posing as a diplomat he worked as a spy (and still is rather hush-hush) collecting intelligence, running covert schemes and recruiting foreign agents. The first stage of consciousness was when the mark “knows that she is in touch with an intelligence service and that something will later be required of her.” The next step was “to motivate, befriend, brief, counsel, debrief, pay and welfare them.” He also had to hunt out secret communists and potential traitors in the British secret service. His career suddenly ended in 1964 when Kim Philby—one of the most notorious double agents working for the Russians—blew his cover. In a witty passage he explained that he always needed an escape hatch. When Finnish friends left the sauna, cut a hole in the ice and prepared to jump in, he refused to join them “because there is only one hole. I need two, I said, one to get into, & one to get out of. Puzzled silence as the Finns slipped one by one into the gloomy chasm of iced sea.”

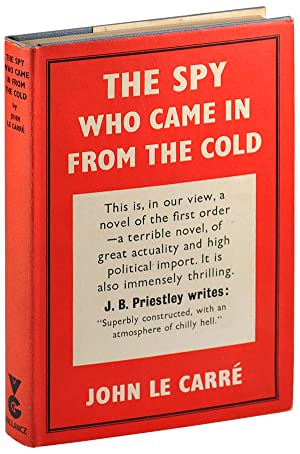

In 1963 the publisher Victor Gollancz reluctantly increased le Carré’s advance from £150 to £175 for The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, which eventually earned £500,000. (The author’s final net worth was $100 million.) The book catapulted him from the shadows into the bright lights. As his reputation grew, he tried to shrink from, while participating in, the unremitting publicity. Despite his professional idealism, his greatest innovation was to eliminate the James Bond-glamour surrounding British spies and portray them as both “murderous, powerful, double-crossing cynics” and “bumbling, broken-down layabouts.” The Spy (which inspired the finest film made from his novels) remained #1 on the New York Times bestseller list for 32 weeks.

His professional success did not help his personal life. In 1965 le Carré wrote, as the marriage to his first wife Ann was disintegrating, “I have been very unhappy for the last year or two & suddenly I can’t take it any more. . . . I’m not God, but she has been sick & wrong.” He then became embedded with Susan Kennaway, his close friend’s wife, who looked remarkably like Ann. He felt terribly guilty about the pain he inflicted on his wife and sons while at the same time celebrating his release from human bondage.

He corresponded with Susan in coded messages and begged her to “try to understand a mole too used to the dark to believe in light.” Ignoring their adulterous affair, he exclaimed, “I love your way of living and understanding. . . . I cannot see how I can ever express my love in a way that will not destroy the things that make your life.” But the death of her husband, the talented, bitter and alcoholic James Kennaway, in a car crash destroyed their liaison. Le Carré described his affair with Susan in his weakest novel, and gave a Schiller-like title to The Naive and Sentimental Lover.

Le Carré replaced Susan with Jane Eustace, who worked in publishing. He married the pregnant Jane in 1972, they had a son, and she was a great help to him as secretary, editor and friend, as keeper of the flame and keeper of the gate. Jane knew she could not have sole possession of her husband, and forgave his dark moods and affairs. He abjectly apologised by saying, “my love-life has always been a disaster” and “no number of ‘sorry’s’ can wipe away my disloyalties.”

The Letters don’t mention the sexy Suleika Dawson, who published a telltale “intimate memoir” in 2022. Though le Carré’s opportunities in Hollywood and elsewhere were bountiful, this book names only two other lovers. The first was Yvette Pierpaoli (1938-99), a French humanitarian and aid worker who was killed in a car crash in Albania. After Yvette’s death her daughter burned his letters.

The great revelation in this volume is his 1996 affair with the African American Museum curator Susan Anderson, not mentioned in Adam Sisman’s 2015 biography of le Carré. Quite swept away, he declared, “I kiss your eyelids, and your erudition, and I send you the rush of the Atlantic storm on the windows of my work room, and I relish you as the most beautiful woman in the world.” Addressing his exotic ideal as if she were on stage, he rapturously continued, “I expect you to be fully & effectively dressed when we meet, jewels, your longest fingernails & at least a ruby in your navel, which I shall remove with my teeth.” When their correspondence was exposed in 1996, he confessed, “the intensity was for me unsustainable, & to continue was to risk more than I was prepared to give up. . . . That we touched something rare is beyond doubt. But that is not the reason to visit misery & solitude on the people round us.”

Every temptation that came with fame seemed futile. Movies and television series brought in millions of viewers and dollars, but he complained that he could “already begin to feel the terrible Hollywooden hand settling on” one of his best projects, The Night Manager, and added, “the idea of ever going back to the Hollywood scene scares me stiff.” The conflict was solved when two of his sons formed the Ink Factory and produced his late films with his approval.

He rightly saw that the great concept of the Nobel Prize had been ruined by political greed (and many unworthy recipients), and mocked C. P. Snow for spending a lot of time in Stockholm while fruitlessly lobbying for the Prize. He turned down the honour of a CBE (Commander of the British Empire), preferring with pique or false pride to stay out of the citadel. He thought that if you lived long enough in Britain and were not rude to the Queen, you eventually got to be distinguished. But he saw the fatal disconnect with these awards: “one’s actual emotions are so remote from the ceremonial expression of things that there’s always a sort of humour-gap.”

As he grew older le Carré expressed clear-sighted anger. He quarrelled publicly with Salman Rushdie, who in his view had provoked his own misfortune and caused several deaths by attacking Islam. He condemned Rushdie for believing “that paperback publication of Satanic Verses is somehow more important to us than the lives of innocent young men and women who work on the outer fringes of publishing.” He cooperated with Adam Sisman’s biography, praised his research about Ronnie’s criminal life but, inevitably, found the reconstruction of his own life intrusive.

He loathed Donald Trump and predicted he “will poison himself with his own sickening doctrine.” He hated Tony Blair’s submission to American demands to send troops to what he saw as the futile war in Iraq. Le Carré was violently opposed to Brexit, “an act of economic suicide mounted by charlatans,” and condemned the British super-rich as obscene and untouchable, without culture or a shred of social conscience. In 2020, to protest conditions in his native country, he took out Irish citizenship through his paternal grandmother, who had brought him up.

Le Carré formed a friendship with Tom Stoppard in his later years, when they exchanged drafts of their novels and plays for expert advice and encouragement. His most intriguing literary connection was with Graham Greene, who was 27 years older and had published his first novel before le Carré was born. In a tribute to Greene he called Spy “a sort of Quiet American story set in Berlin”; Greene boosted sales by praising the novel as “the best spy story I have ever read.” Le Carré then gratefully reciprocated by (absurdly) claiming that The Comedians was Greene’s greatest novel, superior to Mann’s artist-hero stories: “You say quite casually in humanist terms . . . what Mann blared at us with an orchestra and you play gently in clear, solitary themes.”

Graham Greene by FOTO:FORTEPAN / Magyar Hírek folyóirat, CC BY-SA 3.0,

Eventually Greene found le Carré’s novels too long and lost interest in continuing their personal connection. Le Carré was fond of quoting Greene’s statement that every writer should have a splinter of ice in his heart, should be totally analytical and wield a pen as sharp as a knife. He then swung from fondness to revulsion, from adulation and awe to scathing criticism of Greene’s Catholic convictions and communist politics. He found The Honorary Consul and The Human Factor weak, his autobiography A Sort of Life dishonest: “as if being a best-selling novelist for fifty years, living in the S. of France, having lots of money & ladies and discovering God into the bargain all added up to very little.”

Their hostility went public when they quarrelled bitterly about the Russian spy Kim Philby. Greene defended Philby in his introduction to Philby’s My Silent War; le Carré attacked Philby in his long introduction to Bruce Page, David Leitch and Phillip Knightley’s Philby: The Spy Who Betrayed a Generation. Le Carré hated Philby’s father, advisor to King Saud, notorious anti-Semite, spy and traitor. He also hated Kim for betraying his own foreign agents to the Russians and sending them to certain death in Albania. In Moscow he refused to meet Kim, even as a zoological specimen, and called him “a nasty little establishment traitor with a revolting father, a fake stammer and an anguished sexuality who spent his life getting his own back on the England that made him.” (The last words echo the title of Greene’s England Made Me.)

Greene admired Philby’s covert sacrifice; le Carré thought his betrayer was pathologically evil. Greene believed that personal loyalty was more important than patriotism, le Carré was loyal to his country and to the secret service. Greene’s reasoning was perverse, his tone cool; le Carré’s arguments were logical and incandescent with anger. But Greene’s efforts to justify Philby, his sanctified sinner and secret sharer, made him look gullible and fatuous. Le Carré expressed outrage at Philby’s lifetime deceit and “determination to destroy us.” Le Carré clearly won the battle with Greene and Philby remained out in the cold.

II

In the 30 years between September 1989 and February 2018, I received seven letters from le Carré (not included in this volume), two of them handwritten and two-pages long, from his home address in Hampstead. I first sent a brief letter to him through his agent. I introduced myself, mentioned my five previous biographies, offered to send him copies, gave two literary referees in England, asked if he would authorise a life to be sure it would be done by a responsible writer and suggested a meeting the next time I was in London. I was quite astonished, considering his reputation as a difficult, secretive, elusive and intensely private man, to receive his letter only nine days later. Le Carré said he could obviously not object to my proposed biography and would not obstruct my researches. But he did not want to involve himself in my project or authorise a biography. Since he obviously could object to my biography and certainly could obstruct my research if he wished to do so, I interpreted this to mean that he had given his tacit permission to proceed.

Suddenly the wind shifted. Many people, earning enormous sums through their association with le Carré, became extremely nervous about any change that might upset him. On October 20 I received a rather sharp letter from his literary agent Bruce Hunter. He’d heard about my biography proposal from le Carré’s publisher Hodder & Stoughton and wished, on his master’s orders, to put a spoke in my wheel. Le Carré, he stated, acknowledged that I could write what I wished. But he had not given permission, wanted nothing to do with the book and would not cooperate in any way. On October 26 le Carré also said through his agent that he did not want me to interview him for the Paris Review “Writers at Work.”

As my project began to crumble, I wrote to le Carré asking him to clarify the apparent contradiction in his attitude, and let me know if he intended to impede me or allow me to proceed. Alarmed at the prospect of my biography and distracted by the numerous letters and phone calls from trembling dependents on both sides of the Atlantic, le Carré realised that he was getting involved and became intensely irritated. On November 8 he found it necessary to harden his position: he would not help in any way and would actively discourage his friends from doing so. His English agent followed this up nine days later strongly suggesting I abandon the project. Realising the formidable opposition and the impossibility of proceeding against his wishes, I decided—with a certain relief—to give it up.

Considering our acrimonious correspondence and his crushing rejoinders, I was surprised and pleased when he sent me five more letters and even praised my work. He either forgot or forgave our quarrel. I may have caught him in a generous mood or he may have felt he’d treated me rather roughly. Eight years after our blow-up, I again raised the possibility of writing his life story. On August 5, 1997 he wrote more temperately but misleadingly that he’d agreed to give Robert Harris, the bestselling spy novelist, the names of relations, friends and enemies so he could write the biography. Since Harris seemed to have gone quite a long way, le Carré could not provide me with the same assistance.

Nothing daunted, I asked him what George Orwell meant to him as a writer and included his perceptive response in my biography, published in 2000. On September 27, 1998, he observed that Orwell’s life and works were fused into a noble ideal:

Orwell meant and means a great deal to me. . . . Burmese Days still stands as a splendid cameo of colonial corruption. Orwell’s commitment to the hard life is a lesson to all of us. I taught at Eton. It always amused me that Blair-Orwell, who had been to Eton, took great pains to disown the place, while Evelyn Waugh, who hadn’t been to Eton, took similar pains to pretend he had. Orwell’s hatred of greed, cant and the “me” society is as much needed today as it was in his own time—probably more so. He remains an ideal for me—of clarity, anger and perfectly aimed irony.

Emboldened by his letter about Orwell, I persistently raised the question of his biography. It was clear to me that Robert Harris would much rather concentrate on his own profitable books instead of undertaking laborious and expensive biographical research. Harris was merely a dodge and a decoy to discourage other aspirants. But the ever elusive le Carré still insisted, in a letter of March 8, 2000, that the first volume of Harris’ book, on the life up to 1972, would be coming out next year—though it never appeared. He sweetened the pill by adding that he’d read my book Disease and the Novel, which had chapters on Mann and Musil, and was “much rewarded by it.”

Since he now seemed responsive, I boldly asked him, for my next biography, about Somerset Maugham’s career as a spy in Russia during World War I. On his own, with no knowledge of Russian and only $21,000, Maugham’s mission was to support the Kerensky government, prevent the Bolsheviks from taking power and keep Russia in the war against Germany. His dire predictions about Kerensky’s fate were extremely accurate. In his letter to me of November 1, 2001 le Carré got the facts completely wrong. He gave Maugham no credit for his exceptional bravery and insight, and merely recycled malignant gossip: “I know that he was held to have made a complete hash of it, and behaved with a marked absence of courage.” He was also rather severe about Maugham’s spy stories: “I used to have a high regard for the Ashenden series, but as with so much stuff one once admired, it does not bear re-reading.”

Portrait of William Somerset Maugham

In January 2018 I sent le Carré my article in the London Magazine (February 2018) about his clash with Greene on Kim Philby. Replying promptly, as always, on February 12, “to Jeffrey Meyers and with kind regards,” he thanked me for sending the article and said he found it “a fine piece. “ Le Carré’s polite but devious responses about his biography revealed his ambivalence about his own past and suggested how difficult it would have been to write his life while under his thumb.

Jeffrey Meyers, FRSL, has had thirty-three of his fifty-four books translated into fourteen languages and seven alphabets and published on six continents. He’s recently published Thomas Mann’s Artist-Heroes (2014), Robert Lowell in Love (2015), Alex Colville: The Mystery of the Real (2016) and Resurrections: Authors, Heroes—and a Spy (2018), and has just completed a book on James Salter.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.