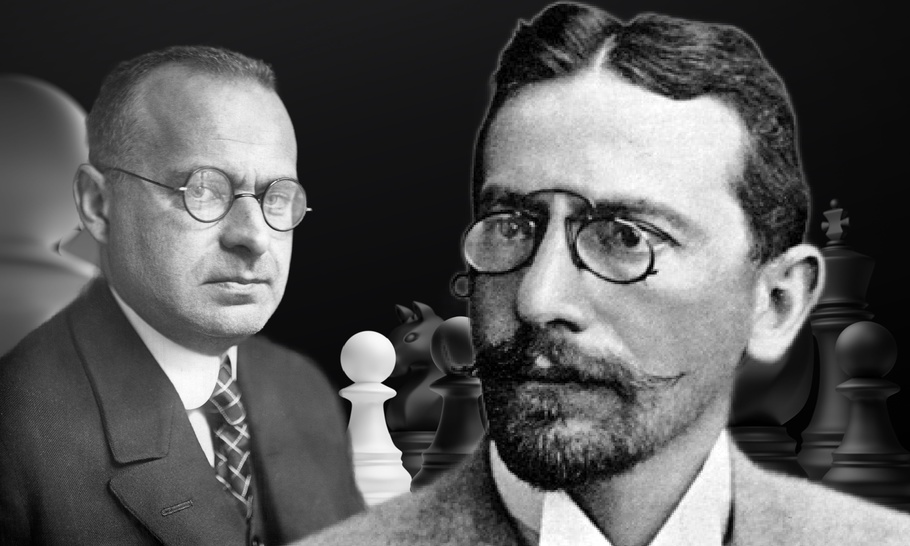

Tarrasch versus Nimzowitsch

Siegbert Tarrasch and Aron Nimzowitsch (image created in Shutterstock)

The history of chess has been marked by numerous epic confrontations. These include Staunton vs. St Amant, a microcosmic struggle from 1843 which acquired particular relevance from memories of the traditional macrocosmic Anglo-French rivalry, culminating at the Battle of Waterloo. Later in the 19th century the rivalry between Steinitz and Zukertort spilled over from the chessboard into literary animosity. Then there was the Spassky vs. Fischer clash from 1972, which reflected the extreme tensions of the USSR vs.USA Cold War battle for global hegemony, coming, as it did, just a decade after the Cuban missile crisis. Thereafter, the colossal five-part Karpov vs. Kasparov series from 1984 to 1990, witnessed the switch of focus to internal Soviet hostilities, between the reforming forces of glasnost and perestroika, pitted against the old school sons of Lenin, who were fighting a reactionary rear-guard action to revive the principles of deathbed Communism.

Among the most celebrated of such hostile conjunctions was the long-standing opposition between the great German writer and chess theoretician, Dr Siegbert Tarrasch (1862–1934), and his ideological rival, the Latvian/Danish genius, Aron Nimzowitsch (1886-1935). Both grandmasters were products of European Jewish culture, so

the antagonism was neither nationalistic nor political, but based on personal antipathy and seemingly opposing, indeed irreconcilable, views on the nature of chess strategy.

A fresh publication from New in Chess, The Philosopher and the Housewife (the latter being one of Nimzo’s least flattering jibes about his great rival) analyses the confrontation between the two. The author, Willy Hendriks, adds for good measure a third actor, the rogue Russian Alapin, into the drama — a man who seems to have terminally irritated everyone with whom he came into contact.

I have no hesitation in pronouncing Hendriks’s work a masterpiece, the like of which we would be lucky to see once in a decade. If this book does not win ECF book of the year, there is no justice in the universe. What are its virtues, let me count the ways:

Research: exhaustive

Scholarship: immaculate

Style: entertaining and dramatic

Comprehension of subject: masterly

Originality of thought: profoundly impressive

Relevance: extreme…the debate about Tarrasch’s favourite, the isolated queens pawn, and Nimzowitsch’s ultimate desideratum, overprotection, rages to this day.

In short, this is the best and most riveting chess book which I have read for years.

Siegbert Tarrasch was one of the most successful tournament players of all time. He shot to fame when he won five consecutive elite tournaments: Nuremberg 1888, Breslau 1889, Manchester 1890, Dresden 1892 and Leipzig 1894.

The most spectacular success of Tarrasch’s long and distinguished career came with his first prize in the Emperor Franz Josef Jubilee tournament at Vienna 1898, a colossal double-round event of 20 masters, in which he tied with the new American star, Harry Nelson Pillsbury, in the tournament proper and went on to defeat him in the play-off. Thereafter, Tarrasch scored two more significant tournament successes: at Monte Carlo 1903 and in the Champions’ Tournament at Ostend 1907 (which was organised in order to establish a “tournament world champion“). In individual games Tarrasch defeated no fewer than five World Champions: Steinitz, Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine and Euwe.

At the perihelion of his early triumphs Tarrasch was offered a World Title match against Steinitz in Havana, but declined. Later he backed out from a virtually agreed Title match against Lasker in 1904. His pretext was that he was too preoccupied with his medical practice, but that did not prevent him from playing extended matches against such opponents as Mikhail Tchigorin, the leading Russian contender, and Frank Marshall, the US champion. The genuine reasons for repeatedly holding back must have been deeper and darker than mere professional obligations, but whatever they were, we shall never know. When Tarrasch did finally agree to challenge Lasker in 1908, he was in his 47th year and well past his best. In terms of active play, Tarrasch was great, but could have been even greater. When destiny called, he twice hung up.

Tarrasch’s immortal fame, however, rests on his writing rather than sporting achievements. With his superbly written books Dreihundert Schachpartien (“Three Hundred Games of Chess”) of 1895 and Die Moderne Schachpartie (“The Modern Game of Chess”) in 1912, as well as his innumerable chess columns and articles, he acquired a reputation as the Praeceptor Germaniae: chess teacher of Germany and, by extension, the world. His swansong, The Game of Chess (1931) — a primer aimed at the widest readership— remains one of the classics of chess literature.

Tarrasch valued the concept of mobility above all. A Freudian explanation for this has been suggested by the German/Jewish/Irish writer Wolfgang Heidenfeld: that Tarrasch attached exaggerated importance to mobility on the chessboard, because in life his own mobility was gravely restricted by a club foot. As the result of this approach he was the supreme advocate of “freeing” moves, especially in the opening, of which the defence to the Queen‘s Gambit which bears his name is a typical example (The Tarrasch Defence: 1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 c5).

The apodictic dogmatism of his opinions may be somewhat off-putting to a modern audience. For example, Tarrasch wrote that, after the moves 1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nd2 the response 3…c5! literally“refutes” White’s third move, since Black can thereby force the acquisition of an isolated queen’s pawn. It was a particular Tarrasch fetish that possession of an isolated queen’s pawn automatically conferred an advantage, a view not entirely endorsed by theory and practice today. Tarrasch was dogmatic, but not alone in his dogmatism. Any reading of the works of Tarrasch’s contemporary, Sigmund Freud, will rapidly reveal a similar self-assurance, which brooks no countervailing alternative opinion. Tarrasch, indeed, was a kind of Freud of the chessboard.

According to Heidenfeld, it was exactly this dogmatism which made Tarrasch’s teaching so effective. His was a time when amateurs still had to learn that a game of chess should not be a haphazard conglomeration of unrelated ideas, but a logical whole.

In his authoritative book, Chess and Chessmasters, magisterially translated by Harry Golombek from the original Swedish, Grandmaster Gideon Stahlberg concurs that at the beginning of the 20th century, Tarrasch occupied a unique place in the chess pantheon. His great tournament successes had granted him a richly deserved reputation as a player, while his widespread literary activities energetically publicised his theories, so that it was not long before he had built up a significant school of followers. “Thus he became the great teacher, whose every word was listened to with hushed attention. To Tarrasch, chess was above all a science. The game followed strict laws and woe to him who broke one of them!”

Suddenly, though, there arose a tempest of contradicting opinion, particularly from one of the younger, less experienced masters: Aron Nimzowitsch. The Balt rapidly made his mark by original, apparently irrational, play, and fought his way into the leading group of the world‘s Masters. After achieving this entry into the “Magic Circle”, he astonished the chess world by a vehement attack against the ancien régime — that is, against the precepts of Tarrasch. At the same time, Nimzowitsch embarked on a fierce campaign on behalf of his own theories.

Nimzowitsch accused Tarrasch of routine dogmatism, and, as we have seen with the case of 3…c5! to a 21st century observer, such an accusation does indeed seem justified. Nimzowitsch also opposed Tarrasch’s conception of the openings, and in substitution propounded a theory of development which welcomed constricted yet resilient positions that were rich in potentialities, just such positions as Tarrasch normally condemned on principle. In my own games, I have frequently followed the Nimzowitschian precepts, heading for seemingly cramped structures which were, however, packed with possibilities for decisive breakouts.

Aron Nimzowitsch, like Tarrasch himself, holds an honoured position amongst those great masters who never became world champion. Nimzowitsch was perhaps the most colourful, making his impressive mark not only with his successful play but also with his profound writings and his eccentric behaviour away from the chessboard.

Born in Riga (then part of the Russian Empire) into the Jewish family of Niemzowitsch, he learnt the moves at an early age from his father — a player of master strength in his own right. It was not until 1904, while in Germany ostensibly to study mathematics that Nimzowitsch began to concentrate on chess. Unlike Tarrasch, Nimzowitsch was never seduced by the temptations of an alternative professional career, away from the chessboard.

At the start of his learning trajectory, Nimzowitsch’s talent seemed to lie in the purely tactical and combinational field, but several failures led him to undertake a complete revision of his chess ideas, placing greater emphasis on positional play, blockading strategy and consolidation. With his changed outlook, Nimzowitsch achieved significant successes, including equal second, behind Rubinstein, at San Sebastian 1912 and equal first with Alekhine at the All-Russian Championship in St Petersburg 1913.

The Great War, combined with the Russian Revolution, brought an abrupt halt to Nimzowitsch’s activities. In 1920 he left Latvia for Scandinavia, changing his name in the process from Niemzowitsch to Nimzowitsch. At first he took refuge in Sweden but eventually settled in Denmark. Nimzowitsch’s return to tournament competition in the early 1920s was disastrous, but gradually he played himself into form. He secured a number of notable successes in the mid-1920s, including equal first with Rubinstein at Marienbad 1925, first at Dresden 1926 (scoring 8½ out of nine, ahead of Alekhine and Rubinstein) and first at Hannover 1926. He also garnered two first prizes in strong tournaments in London during 1927. It was during this rich period that Nimzowitsch’s most influential work appeared: Mein System (“My System”). Published in 1925, it underwent several revisions until 1928 and is still a bestseller in many translations over the entire chess-playing world.

Nevertheless, the World Title still eluded him. Nimzowitsch took third place in the prestigious New York tournament of 1927, behind Capablanca and Alekhine. His brilliant first prize at Carlsbad 1929 was achieved ahead of Capablanca, Spielmann, Rubinstein, Euwe, Vidmar and Bogoljubow, yet Alekhine (by then World Champion) was not competing. His performance at Carlsbad possibly justified Nimzowitsch in adopting the title “Crown Prince of the chess world“ which he then assumed — somewhat pompously, given that he never managed to beat Capablanca. Yet Alexander Alekhine, the reigning monarch, refused to give way and the crown prince never managed to secure the funds for a world championship match.

Nimzowitsch’s best results in major tournaments from 1929 onwards (2nd at San Remo 1930, 3rd at Bled 1931) were achieved in the shadow of the mighty Alekhine, against whom he won three games, lost nine and drew nine. Ill-health caused Nimzowitsch’s sudden decline in the mid-1930s and he died, just 48 years old, at the Hareskov Sanatorium, Copenhagen, in 1935.

In his playing style Nimzowitsch belonged to the so-called Hypermodern School, which held (inter alia) that control of the centre did not necessarily imply occupation by pawns. Adherence to these views, combined with a decided mutual incompatibility, brought him into frequent opposition with the great exponent of the classical school, Tarrasch. Neither master was averse to self-adulation and the bitterness emanating from their first meeting in 1904 was never entirely eradicated. In fact, hostility towards Tarrasch and his works was a recurring theme of Nimzowitsch’s literary endeavours.

However, Nimzowitsch’s major contribution to chess literature consisted not in his ridicule of Tarrasch, nor yet in the discovery of a novel method of play, but in his elaboration of a new chess vocabulary which made intelligible the hitherto but vaguely articulated strategy of master-strength players. Nimzowitsch possessed an unrivalled facility for capturing the essence of an already known operation or structure with a memorable and meaningful word or phrase, which thereby increased speed of comprehension and assisted clarity of thought. Nimzowitsch introduced into chess terminology such phrases as “the passed pawn’s lust to expand”, “the mysterious rook move”, “prophylaxis”, “7th rank absolute”, “isolani” and “hanging pawns”. It is an established phenomenon that rapid advances in performance are often immediately preceded by advances in modes of expression, and we may indeed detect an upsurge in the general level of chess after the publication of My System.

Nimzowitsch’s writings were penned with such enthusiastic and allusive wit that only the most hardened could resist the appeal of his message. Consider the following passage on Tarrasch’s favourite hobby horse, the isolated queen’s pawn: “… we no longer consider it necessary to render the enemy isolani absolutely immobile; on the contrary, we like to give him the illusion of freedom, rather than shut him up in a cage (the principle of the large zoo applied to the small beast of prey).”

The rivalry between Tarrasch and Nimzowitsch is a common trope of chess literature, yet sometimes (as with Hendriks) I wonder whether the gulf between their relative visions of chess strategy is quite so wide as is commonly supposed. Nimzowitsch was known as an early advocate of 3. e5 against the Caro Kann Defence, namely 1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 and now 3.e5. Yet, where did this advance first crop up? It was played by Tarrasch himself against Nimzowitsch in their game at San Sebastian in 1912.

I have frequently maintained that chess as a game of war, mirrors battlefield strategy of the day. Thus chess originally reflected the chariots, foot soldiers, cavalry and war elephants of the ancient Indian army. During the Renaissance the chess queen acquired her rampant new powers, a metaphor for the new distance weapon, the cannon. Most strikingly, given that the prime modus operandi of warfare in 1914-1918 consisted of trench and blockade operations, both on land in Flanders and at sea, after the Battle of Jutland, the blockade in chess came to the fore.

Indeed, both Tarrasch and Nimzowitsch were expert blockaders (see the game Tarrasch vs. Georg Marco). There is yet another point of chess board consanguinity between the two: it is normally held that Tarrasch preferred to occupy the centre with pawns, while Nimzowitsch preferred central domination by pieces. This was an argument made vehemently by that Pontifex Maximus of Hypermodernism, Richard Réti, in his classic Masters of the Chessboard, published posthumously in English in 1933. In that context, the win by Nimzowitsch against the strong Polish master Georg Salwe was considered revolutionary. However, now examine the Tarrasch win against Max Kuerschner, the president of Tarrasch’s own chess club in his home city of Nuremberg, played 31 years earlier. These two games are strikingly similar and it is hard to credit that the two victors maintained an exclusively diametric opposition of views on all chess strategic thinking.

As a modest incursion into the realms of speculation, it almost seems that Freud is even more relevant than might at first sight appear. Freud’s Oedipus Complex requires the son to kill the father. Nimzowitsch’s attempt to slay Tarrasch, who was 24 years older, could in fact have been a reaction to their overt similarities. Was Nimzowitsch trying to kill his chessboard father?

What,bone might ask, can modern chess games tell us about contemporary warfare? I enter here the realms of further extreme speculation, but Bongcloud openings (1. e4 e5 2. Ke2), early queen sorties based on Qh5 and deliberate tempo loss (1. c3 followed swiftly by c4), all practised by the elite, including the current first ranked player and former World Champion, Magnus Carlsen, indicate to me that the direction of conflict is towards asymmetric warfare. This involves terrorism, surprise, psychological combat and guerilla tactics, rather than the stately orchestration of grand strategy, as might have appealed to a Capablanca, a Botvinnik, a Karpov — or indeed Tarrasch and Nimzowitsch.

Meanwhile, within the confines of the chessboard, Nimzowitsch’s words still ring true: “Ridicule can do much, for example, it can embitter the existence of young talents; but one thing is not given to it, to put a stop permanently to the incursion of new and powerful ideas.”

The games I have selected this week are two of my own. In my win against Tony Miles I side with Tarrasch and demonstrate the virtues of the isolated queen’s pawn. Meanwhile, in my win against Basman, I switch to following Nimzowitsch and show how relentless overprotection of the key point on e5 can unleash elemental fury, once the time comes to activate the forces in support of the designated strongpoint. In this case White has a knight, rook, bishop and queen all accumulating energy in contact with the focal square. In truth, both of these outstanding players and teachers, had a vast store of important information to impart to future generations, as Hendriks rightly proves in his latest magnificent contribution to the elite literature of chess.

Most strikingly of all, at a time when antisemitism is once again rearing its hideous head, it is worthwhile recalling that both Aron Nimzowitsch and Siegbert Tarrasch (not to mention Sigmund Freud) were great Jewish teachers and thinkers. Nimzowitsch elevated the interpretation of blockading strategy (also a Tarrasch trademark) to new heights, as in his celebrated win with the black pieces against Johner from Dresden 1926. This was notably the forerunner of the Hubner system in the Nimzo-Indian, which Bobby Fischer deployed to such devastating effect in game five of his celebrated match victory in 1972, against the incumbent champion, Boris Spassky in 1972.

Johner vs. Nimzowitsch, Dresden, 1926

Spassky vs. Fischer, Reykjavik, 1972

Nimzowitsch is regarded by many as the author of what might be termed the chess players’ strategic Bible, My System, but excoriated by others as irrelevant or at times even incomprehensible.

First of all, let me establish Nimzowitsch’s credentials as a role model.

In terms of opening theory, his most enduring contributions have been the Nimzo-Indian Defence and the complex of systems starting with 1. b3 or 1. Nf3 followed by b3. As a player he defeated Alekhine, Lasker and Euwe in individual games and won, or shared first prize, in such powerful events as Marienbad 1925 (11/15), Dresden 1926 (8½/9), London 1927 (8/11) and above all Carlsbad 1929 (15/21) where he triumphed ahead of Capablanca, Spielmann, Rubinstein and Euwe.

So, why have some critics denigrated the Jewish maestro’s contribution to chess knowledge, science and practice?

Let us take four pillars of his thinking, the blockade, prophylaxis, centralisation and over-protection. Those in the anti-Nimzo brigade have pointed out that the blockade existed before Nimzowitsch, notably and ironically in the games of his arch enemy Tarrasch. Nevertheless, Nimzowitsch elevated the interpretation of blockading strategy to new heights, as we have seen from the links above.

Centralisation, too, was known and practised well before Nimzowitsch came on the scene. To be fair, I do not think that Nimzowitsch claimed to have invented either centralisation or the blockade, merely to have observed such mechanisms and refined them. However, with chess being a game which simulates warfare, I do believe that the prime battle modes of the First World War, trench combat and naval strangulation, did influence Nimzowitsch’s blockade-oriented writings of the early 1920s.

This brings us to prophylaxis, the anticipation, restriction and prevention of the opponents’ potential for attack. Again, I think that Nimzowitsch observed this methodology in the games of contemporary masters, and his chief contribution was to identify and name it. Certainly, world champion Tigran Petrosian ( 1963-1969) made it completely clear that prophylaxis, as taught by Nimzowitsch through Petrosian’s trainer Ebralidze, was highly influential in forming his own chess style. His win in the following game against Bobby Fischer is a notable example of the genre.

Petrosian vs. Fischer, Candidates, Bled-Zagreb-Belgrade,1959

Now we come to the more opaque concept of over-protection. Even ex-world champion Magnus Carlsen has confessed to a certain bafflement where this is concerned and – make no mistake – over-protection was very much Nimzowitsch’s primary strategic insight and was exceedingly close to his heart. Overprotection is to Nimzowitsch as E=mc2 is to Einstein or Mind Mapping to Tony Buzan.

Prophylaxis and the mysterious rook move are far simpler to grasp, even in the extreme mode of Garry Kasparov’s doubling of his rooks on e7 and e8 in the closed e-file in game 24 of the 1985 world championship match against Karpov, the game which crowned Kasparov as the youngest ever world champion.

Karpov vs. Kasparov, Moscow, 1985, game 24

Over-protection is less clear, both in terms of its relevance and its usefulness. What I think has been overlooked is that the concept of over-protection (concentrating force on a key point in order to maximise energy) has morphed into specific opening variations, where it is just second nature and disguised from its original function as a discrete strategic device.

As is well known, Nimzowitsch favoured 3. e5 against both the French and Caro-Kann defences. The latter is now more in vogue than the former, though Nimzowitsch himself predicated the rationale for both as being over-protection of e5. A clearer instance of over-protection evolving into a popular opening variation is White’s control over d5 in most lines of the highly fashionable Sveshnikov variation of the Sicilian.

Perhaps the clearest manifestation, though, is White’s concentration of force behind his e5 pawn in many variations of the King’s Indian attack.

The example game which follows reveals a consistent policy of over-protection, with White over-protecting the pawn on e5 with knight, bishop, queen and rook. Once the e5 pawn advances, the forces in support break out with elemental fury and sweep Black from the board.

Raymond Keene vs. Michael John Basman

Preparation Tournament for Student Olympiad, 1967, Bognor Regis

- e4 e6 2. d3 b5!?

An eccentricity quite in Basman’s style. However, the move also has some positional basis in that an eventual advance of the queenside pawns forms a valuable black resource against the King’s Indian Attack.

- Nf3 Bb7 4. g3 Nf6 5. Bg2 Bc5?!

But this is much harder to justify, since the king’s bishop is normally needed on the kingside for defensive purposes.

- O-O O-O 7. Nbd2 d6 8. Qe2 Bb6

Necessary if Black is to mobilise his c-pawn.

- Kh1 c5 10. Nh4 Nc6 11. c3 d5 12. e5 Nd7 13. f4 b4 14.Ndf3

White’s kingside attack proceeds unopposed, largely due to the absence of the useful defensive king’s bishop.

14… Qc7 15. f5! exf516. Bf4 Rae8 17. Rae1 bxc3 18. bxc3d4 19. c4 Re6

Although White’s e-pawn is blockaded there are other ways of prosecuting the assault.

- Nxf5 f6?

Threatening to destroy White’s strong point at e5, but the scheme is over-optimistic and allows the energy in White’s position to burst forth by means of a positional queen sacrifice.

- Nxg7! Kxg7 22. exf6+ Rfxf6 23. Qxe6! Rxe6 24. Rxe6

White avoids 24. Bxc7? with only rook for two minor pieces. White has now given up queen and knight for two rooks, but Black’s famous king’s bishop is locked out of play, while his other pieces cannot participate in the defence of his king.

24…Qc8 25. Bh6+ Kg8 26. Ng5

Threatening Bd5 and Rf7.

26…Nce5 27. Bxb7 Qxb7+

Although Black gains a temporary respite with this check his queen must immediately return to the back rank to prevent Re8+.

- Kg1 Qb8 29. Re7 Ba5 30. Rg7+ Kh8 31. Nf7+ Nxf7 32.Rgxf7!

Threatening both Rxd7 and Rf8+.

32…Bd2?!

Obviously desperation. If 32… Qc8 33. Rxd7+- or 32… Qd6 33. Rf8+ Nxf8 34. Rxf8+ Qxf8 35. Bxf8 with a simple win in the endgame.

- Bxd2 Qd6 34. Rxd7 Black resigns 1-0

After 34… Qxd7 35. Bh6 wins at once.

To conclude: amongst those prominent individuals who fail to appreciate Nimzowitsch, I would, among others, include Yasser Seirawan, Jan Gustafsson and World Champion Max Euwe (1935-1937), with Magnus Carlsen somewhat ambivalent. In the Nimzowitsch camp I would firmly place Bent Larsen, Tigran Petrosian, Mikhail Botvinnik (who loved the Nimzowitschian e4/c4 pawn structure in the English opening and who was also a staunch upholder of Nimzowitsch’s favourite response 3… Bb4 in the Winawer French). Not to overlook the Icelandic former world title candidate, Johann Hjartarson, who gave ample recognition to Nimzowitsch in a keynote lecture in 2019 at the Gibraltar Masters.

Hastings International, 1975/76, rd. 13

- Nf3 Nf6 2. c4 c5 3. Nc3 Nc6 4. e3 e6 5. d4 d5 6. cxd5 Nxd5 7. Bd3 cxd4

Perhaps 7… Be7 is more accurate, maintaining the central tension.

- exd4 Be7 9. O-O O-O

One of the classical isolated queen’s pawn positions, in which White’s extra space and attacking chances compensate for the structural weakness.

- Re1 Nf6

A solid alternative is 10… Bf6 11. Be4 etc.

- Bg5!?

Fashionable was 11. a3, but the text is not bad. All White’s pieces are coming out at great speed while Black still has problems completing his queenside development.

11… Nb4

The immediate 11…b6 deserves attention. Black’s plan to dominate the blockade square d5 instantly is possibly too straightforward.

- Bb1 b6

12… Bd7 is a more cautious treatment, planning a later development with …Bc6.

- Ne5 Bb7

It might look as if Black is over the worst but now a vicious attack appears almost out of nowhere.

- Re3!!

A difficult and bold move. When I played it I already had to be sure that my kingside attacking chances would be sufficient compensation for my lack of queenside development and the clumsy position of my rook on the third rank. Strangely, a similar rook manoeuvre occurred in a game Filip – Pogats, played 14 years previously, but neither Miles nor I had any notion of this until I discovered the theoretical background after our game. Incidentally, the Filip game ended in a draw.

14…g6

To prevent 15. Bxf6 Bxf6 16. Bxh7+ Kxh7 17. Qh5+ and 18. Rh3.

- Rg3!

It looks odd to aim the rook against a granite wall (g6) but the granite has faulty foundations. In contrast, the more natural 15. Rh3 achieves nothing.

15…Rc8?!

At the time the course I feared most was 15… Nc6! 16. Bh6 Qxd4! when Black breaks White’s attack by sacrificing the exchange. In view of the lack of weaknesses in Black’s position it would then be a distinctly uphill struggle for White to win. After the move played the solution became susceptible to precise tactical analysis.

- Bh6 Re8 17. a3 Nc6

17…Nbd5 does not alter things significantly.

- Nxg6! hxg6 19. Bxg6

Apart from capturing the bishop Black has two other defences: a) 19… Bf8 20. Bc2+ Kh8 21. Bxf8 Rxf8 22. Qd2 Ng8 23. Rh3+ Kg7 24. Rh7+ (Fritz gives 24. Qf4) 24… Kf6 25. d5+-; b) 19… Bd6 20. Bxf7+ Kxf7 21. Rg7+ Kf8 22. Qf3+-. In this position Black is quite helpless, in spite of his extra material.

19… fxg6 20. Qb1!

An original square for the queen in a mating combination, but neither 20. Qd3 Ne5 nor 20. Qc2 Ne5! 21. dxe5 Ne4 (exploiting the pin on the c-file) would be good enough for White.

20… Ne5 21. dxe5 Ne4

Without the c-file pin (see above note for 20. Qb1!) this is sheer desperation.

- Nxe4 Kh7 23. Nf6+ Bxf6 24. Qxg6+ Kh8 25. Bg7+ Bxg7 26. Qxg7 checkmate 1-0

This Tuesday, May 13, there will be an evening reception and dinner at L’Escargot to celebrate the paperback launch of Chess through the Looking Glass. The all-inclusive price is £75. This is an opportunity for readers of TheArticle to meet your chess columnist, the Editor, Daniel Johnson and other chess luminaries over a meal at one of London’s most famous restaurants. For further details please contact Ima von Wenden at secretary@snailclub.co.uk

Ray’s 206th book, “ Chess in the Year of the King ”, written in collaboration with Adam Black, and his 207th, “ Napoleon and Goethe: The Touchstone of Genius ” (which discusses their relationship with chess) can be ordered from both Amazon and Blackwells. His 208th, the world record for chess books, written jointly with the chess-playing artist Barry Martin, Chess through the Looking Glass , is now also available from Amazon.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.