The very singular Félix Vallotton: review

The Baltimore Museum of Art. Photography: Mitro Hood

A large group portrait of five men. All wear dark suits and sombre expressions. Some resemble serious undertakers, some look like doleful clergymen, and at least one could pass for a man in mourning. They are in fact painters – a choice selection of the circle of artists known as the “Nabis” or “Prophets”. Two of the most famous members, Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard, are present and correct. So too is their close friend and the man behind this 1902-03 artwork. When Swiss-born Félix Vallotton (1865-1925) joined the group in 1893 his French peers nicknamed him le nabi étranger – “the foreign Nabi”. However, it wasn’t just his nationality that rendered him foreign. His style also set him apart. Although he adopted the Nabis’ anti-naturalist approach for a while, he never fully embraced it. His true inclination, and indeed his genuine talent, was not for emotional expression but rather clean-cut and occasionally hard-edged realism. After sticking out for so long, Vallotton eventually parted company and changed direction.

He certainly sticks out in The Five Painters. Here is a reluctant recruit, the token black sheep. He can be seen standing on the left and at a remove from his associates. He is staring off into space, lost in thought, disengaged from the others. He is the only one with a short, downward stroke of a beard, the only one with half-hidden, inexpressive hands, the only one hovering uselessly in the background. He is the sole onlooker and eavesdropper, a peripheral entity, an almost redundant figure who could slip away unnoticed, his presence neither felt now nor missed later.

The opposite is the case in Vallotton’s commanding self-portraits. A new exhibition of his work at the Royal Academy – the first such show in the UK for over forty years – opens with the astonishing Self-portrait at the Age of Twenty (1885). The likeness is uncanny. Take a step back and we might well be looking at a photograph. This early piece was painted in Paris, four years after Vallotton exchanged provincial Lausanne and his strict Protestant family for both personal and creative freedom in the capital of the art world. A remarkably self-assured man in complete control of his emotions and perhaps even his destiny stands in profile and coolly meets our gaze. This painting, along with The Coffee Service (1887) – featuring a silver pot so perfectly polished we can almost see our reflection in it – fully exemplify the young artist’s rigid discipline and precocious flair.

And yet the real stand-out piece from this period is The Sick Girl (1892). Demonstrating Vallotton’s admiration for, and debt to, seventeenth-century Dutch masters, this mesmerising painting excels on several levels. The two female subjects intrigue: our eyes flit from the bedridden woman to the healthy maid entering the room with a tray. The former is turned away from us, transfixed by the wallpaper; the latter is staring ahead, diligently ignoring her mistress. The room is light, airy, open and spacious but at the same time is made up of rich, finicky detail, from objects to patterns: the woven seat of the chair, the tessellated squares on the rug, the glass bottle reflecting an unseen window. Though undoubtedly pretty, the painting nevertheless conveys hints of unease. Just how sick is the sick girl? How beneficial are the contents of those vials and bottles? And is the maid simply concentrating on not dropping her tray or does her averted gaze signify indifference?

This discomfort is at the heart of much of the work on display. It is no surprise that the exhibition is titled “Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet”. Vallotton is incredibly subtle, offering only intimations of concern, notes of discontent, often in scenes or portraits of great beauty. It is up to us to make sense of our queasiness: either we overcome it and accept the work as a vision of purported innocence, or we succumb to it after locating a deliberate sinister streak. The Red Room (1898), one of six pictures in distemper on cardboard depicting a behind-closed-doors romantic exchange between a man and a woman, shows the couple in a clinch in a living-room. However, they are removed from the riot of red furnishings: they stand shrouded in shadow in a doorway that presumably leads to the bedroom. Neither appears completely relaxed, suggesting that this is an illicit liaison. On the mantelpiece in the room we discern a spy in the house of love: a bust of Vallotton, both creator and voyeur.

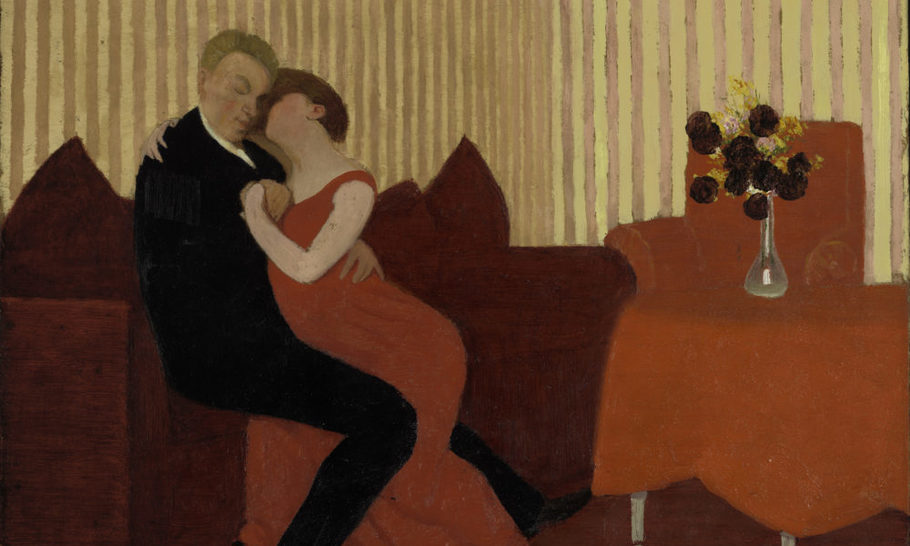

Another painting from the same year in this sequence confirms that these are snapshots of adulterous assignations. Five O’Clock refers to the hour when French men visited their mistresses. The couple here look happier and certainly more comfortable – he seated, she on his lap – and there is every indication that this snatched hour or stolen moment will be fulfiling. And yet they also seem hemmed in, their intimacy hampered, even threatened by the busy furniture and careless clutter around them.

This suite of paintings is one of the supreme highlights of the exhibition. Equally entrancing and thematically similar are the ten woodcuts Vallotton produced around this time. Entitled Intimacies, these black-and-white scenes are arguably more effective studies of the sexual mores of the Parisian bourgeoisie. Devoid of bright and often lurid colour, they are rawer, starker, more striking narratives. The pitch-darkness transforms the figures into silhouettes and underscores their deceit and duplicity. They are shady individuals lurking in the gloom or being engulfed by it. Further monochrome prints from other stages in Vallotton’s career reinforce his ability to encapsulate drama and transmit tension. His caricatural illustrations of Parisian society from the early 1890s are profoundly disconcerting – a far cry from the warm and sumptuous 1898 triptych The Bon Marché Department Store. Again and again we see cartoon characters exposed to pain: crowds of people run amok in anarchic demonstrations or are battered in brutal police charges; a ferocious gust of wind blows a dog through the air and a horse out of control tramples a woman crossing the road. The woodcuts that made up Vallotton’s last print portfolio This is War! capture the horrors of the Western Front, from dead soldiers snarled up in barbed wire to terrified families hunkered down in a cellar.

This riveting exhibition showcases Vallotton’s considerable range. Other examples of his genre-juggling expertise include still lifes, landscapes and nudes. Red Peppers from 1915 appears innocuous enough until we see the smear of red on a gleaming knife-blade. The White and the Black (1913) audaciously repurposes Manet’s Olympia by demoting the white naked woman to the background and repositioning the black maid at the front, where she sits nonchalantly smoking a cigarette. And The Pond, a disorienting work from 1909, presents a cloud of beautiful blossom, and beneath it a mass of dark, ominous water spreading like an oil slick towards a verdant shoreline.

The foreign Nabi was also called the “very singular Vallotton”. This overdue exhibition demonstrates how this distinctive artist honed his craft with the Nabis and then ploughed his own furrow, producing original and diverse wonders that still have the power to amaze and unsettle.

Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet is exhibited at the Royal Academy, London, until September 29. For more information see