A hundred years of exactitude: José Raúl Capablanca

(Alamy)

In the summer of 1922, a century ago, London played host to a galaxy of international chess stars, including Alexander Alekhine , Akiba Rubinstein and Efim Bogoljubov. But the most incandescent amongst this stellar congregation was the Cuban genius, José Raúl Capablanca. The previous year Capa, as he was widely known, had crushed the incumbent world champion, Emanuel Lasker, by the score of four wins to zero, with ten draws. This was one of the very few world title clashes in which the winner lost no games at all. Indeed, Capa established a reputation for invincibility and accuracy which remains undiminished to this day.

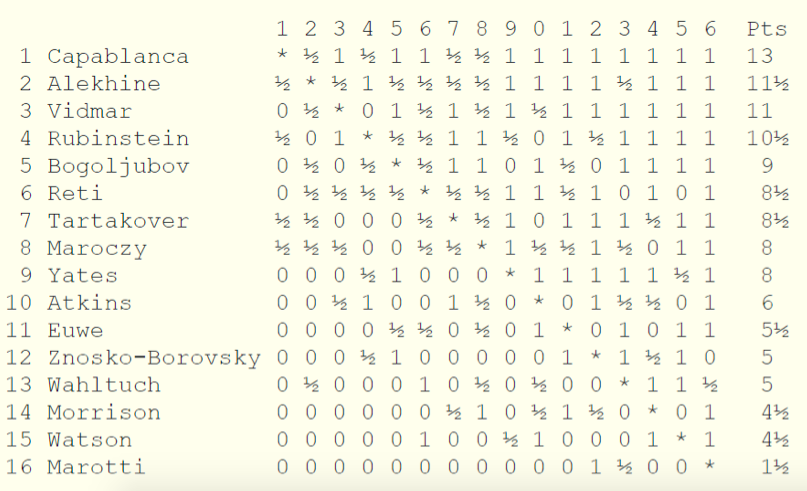

Full cross table of London 1922

José Raúl Capablanca y Graupera (1888-1942) was world chess champion from 1921-1927. Apart from accuracy and invincibility, Capa was widely renowned for his exceptional strategic vision, endgame skill and speed of play.

Capablanca ’s victory over the dominant American champion, Frank Marshall in a 1909 match earned him an invitation to the 1911 San Sebastian tournament, which, against all initial odds, he won ahead of players such as Akiba Rubinstein, Aron Nimzowitsch and Siegbert Tarrasch. Capa only received his invitation at Marshall’s generous insistence and over the objections of established Grandmasters, Aron Nimzowitsch and Ossip Bernstein. This grandmasterly duo complained about the inclusion of a relative neophyte, but in an almost inevitable stroke of poetic justice, Capa trounced both of them in their individual encounters.

Capablanca finally won the world chess championship title from Emanuel Lasker in 1921 , thus contributing to an extraordinary record in that Capa was undefeated from 10 February 1916 until 21 March 1924, a period that included the world championship match against Lasker. To go for eight years without loss, including several international standard tournaments, a world championship match and the cosmic gathering in London a century ago, is a record which is likely to stand until chess as we know it is no longer played.

Capablanca lost the title in 1927 to Alexander Alekhine, who, astonishingly, had never beaten Capablanca before this match. Following unsuccessful attempts to arrange a rematch over subsequent years, relations between the two colossi became embittered. Capablanca continued his excellent tournament results, including first prizes in Moscow and Nottingham, but he also suffered from symptoms of high blood pressure. He died in 1942 of a brain haemorrhage.

Capablanca excelled in simplified positions and endgames; Bobby Fischer, employing his easy going transatlantic vernacular, described him as possessing a “real light touch”. He could play tactical chess when necessary, although he rarely invited complications, and possessed iron defensive technique. He wrote several chess books, of which Chess Fundamentals was regarded — somewhat controversially, I might add — by Mikhail Botvinnik as the best chess book ever written.

Despite his books, Capablanca preferred not to engage in detailed analysis but focused on critical moments in a game. His style of chess influenced the play of future world champions such as Vassily Smyslov, Tigran Petrosian, Bobby Fischer and Anatoly Karpov. A major difference, though, was Capa’ s reluctance to research and innovate in the openings and his reliance on his own instinct, talent and genius to support him in any situation or predicament.

Five years after his triumph in London, Capa undertook his most strenuous challenge since his struggle with Lasker for the world sceptre. The New York chess tournament, held between 19 February and 23 March 1927, involved six of the world’s strongest masters playing a quadruple round-robin, with the others being Alexander Alekhine, Rudolf Spielmann, Milan Vidmar, Aron Nimzowitsch and Frank Marshall.

Before the tournament, Capablanca wrote that he had “more experience but less power” than in 1911, that he had peaked around 1919 and that some of his competitors had gained in strength in the intervening years. In spite of such pessimistic forebodings, Capablanca enjoyed overwhelming success, finishing undefeated with 14/20, winning the micro-matches with each of his rivals, 2½ points ahead of second-placed Alekhine, and won a special prize for a victory over Spielmann.

Since Capablanca had won the New York 1927 chess tournament overwhelmingly and had never lost a game to Alekhine, most pundits regarded the Cuban as the clear favourite in their World Chess Championship 1927 match. But Alekhine won the match, played from September to November 1927 at Buenos Aires, by 6 wins, 3 losses, and 25 draws — the longest World Championship match ever, until the aborted contest in 1984–85 between Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov.

Alekhine’s victory surprised almost the entire chess world. After Capablanca’s passing, Alekhine himself expressed surprise at his own victory, since in 1927 he had not truly believed that he was superior to Capablanca, and he suggested that Capablanca had been overconfident. Capablanca entered the fray with no technical or physical preparation, while Alekhine trained himself into good physical condition and had closely studied Capablanca’s play, in the course of which thorough investigation he convinced himself that he had found some promising chinks in the champion’s armour.

In his last major appearance, Capablanca played for Cuba in the 8th Chess Olympiad, held in Buenos Aires in 1939, and won the gold medal for the best performance on the top board. According to the extensive essay on Capa to be found on Wikipedia, for which I am grateful for many of the facts in this column, while Capablanca and Alekhine (France) were both representing their countries in Buenos Aires, Capablanca made a final attempt to arrange a World Championship match. Alekhine declined, saying he was obliged to help defend his adopted homeland, since World War II had just broken out. This was a strange decision, since Alekhine was then in his late forties and an unlikely candidate for strenuous or indeed any military service. As fate would have it, Alekhine would have done better to stay in Buenos Aires and contest a match against Capablanca on the spot.

Alekhine wrote in a 1942 tribute to Capablanca: “Capablanca was snatched from the chess world much too soon. With his death, we have lost a very great chess genius whose like we shall never see again.” Lasker once said: “I have known many chess players, but only one chess genius: Capablanca.”

Capa has been an inspiration for chess in Cuba ever since, culminating in the 1966 Havana Olympiad, where I, as a member of the England team, was even invited to dinner with Fidel Castro. An annual Capablanca Memorial tournament has also been held in Cuba, most often in Havana, since 1962. In 1974 I had the honour of being invited and winning the Capablanca Masters.

Astonishingly, Capablanca lost only 34 serious tournament and match games during his adult career. Again, according to Wiki statistics, he was undefeated from 10 February 1916, when he lost to Oscar Chajes in the New York 1916 tournament, to 21 March 1924, when he succumbed to the revolutionary Hypermodern complexities of Richard Réti in the New York International tournament. During this unbeaten streak, which included his 1921 World Championship match against Lasker, Capablanca racked up 63 tournament or match games, winning 40 and drawing 23.

In fact, only Frank Marshall, Emanuel Lasker, Alexander Alekhine and Rudolf Spielmann were able to win two or more formal games from the mature Capablanca, though in most cases their overall lifetime scores were minus (Capablanca beat Marshall +20−2=28, Lasker +6−2=16, Alekhine +9−7=33). Only Spielmann was level (+2−2=8). Of top players, Paul Keres alone had a narrow plus score against Capa (+1−0=5). Keres’s sole win came at the AVRO tournament of 1938 in Holland. This event was staged on the peripatetic principle of holding different rounds each day in separate towns. During this tournament Capablanca turned 50, while Keres was 22. It was overall Capa’s worst performance and it can certainly be explained, partly by age disparity, poor health and constant travel favouring younger players, but also by Capa’s infelicitous choice of the French Defence, which did not suit his fluid style.

Statistical ranking systems place Capablanca high among the greatest of all time. Nathan Divinsky and I, in our book Warriors of the Mind (1989) ranked him fifth, behind Garry Kasparov, Anatoly Karpov, Bobby Fischer and Mikhail Botvinnik — but immediately ahead of Emanuel Lasker. In his 1978 book The Rating of Chessplayers, Past and Present, Arpad Elo allotted retrospective ratings to players based on their performance over the best five-year span of their career. He concluded that Capablanca was the strongest of those surveyed, with Lasker and Botvinnik sharing second place.

Most importantly for my theme, a 2006 engine-based study found that Capablanca was the most accurate of all the World Champions, when compared with computer analysis of World Championship match games. This was confirmed by a 2011 computer analysis from the duo of Bratko and Guido, using the strong engines Rybka 2 and Rybka 3. In other words, Capa had, up to that moment, been the most exact champion of all time, certainly of the champions who trained without computers in the pre-Carlsen era.

Boris Spassky, World Champion from 1969 to 1972, considered Capablanca the best player of all time. As we have seen, Bobby Fischer, who held the title from 1972 to 1975, admired Capablanca’s “light touch” and ability to see the right move instantly. Fischer reported that in the 1950s, veteran members of the Manhattan Chess Club recalled Capablanca’s blitz chess exploits with absolute awe.

Capablanca excelled in simplified positions and endgames, and his strategic judgment was outstanding, to such an extent that attempts to attack him directly almost always foundered on his impervious defence. Nevertheless, Capa could also play stirring tactical chess when necessary — most famously in the 1918 Manhattan Chess Club Championship tournament, when Frank Marshall sprang a deeply analysed prepared variation on him, which he refuted while playing under the constraints of a time limit. He was also capable of aggressive tactical play to exploit a positional advantage, provided he considered it the most secure and efficient way to win — for example against Spielmann in the 1927 New York tournament.

In summary, Capa was a phenomenon, a sportsman without nerves, blessed with astoundingly rapid sight of the board and a nearly infallible instinct for the right move in any situation. If, as I believe, mathematics, music and chess in some way manifest the harmony of the universe, then Capablanca represents chess in the way that Pythagoras stands for mathematics and Mozart exemplifies music.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout the pandemic. So please, make a donation.