Tim O’Brien: the guilt of war

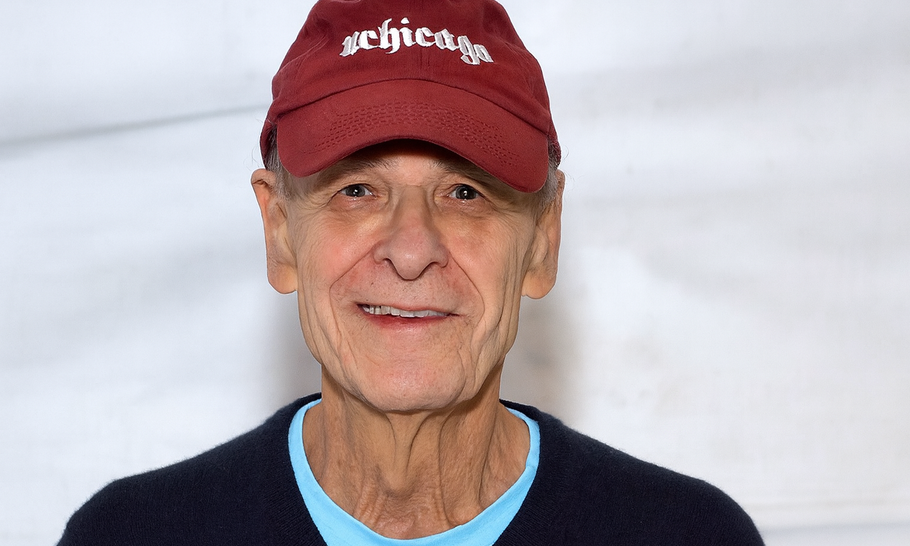

O'Brien at the 2023 Texas Book Festival

Tim O’Brien wrote three important and successful books about Vietnam: a memoir If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home (1973), a novel Going After Cacciato (1978; the Italian name means “hunted”) and stories The Things They Carried (1990), which sold an astonishing 6 million copies. John Updike’s review of If I Die helped establish O’Brien’s reputation, as Saul Bellow had done for Isaac Singer and Philip Larkin for Barbara Pym. The things the soldiers carried were a Homeric catalogue of military and personal possessions. The soldiers cruelly kicked corpses to scatter the flies, cut off thumbs to keep as souvenirs, and incinerated people and villages with napalm and Agent Orange.

O’Brien was born in 1946, grew up in a small town in Minnesota and graduated from Macalester College in that state. Five feet, seven inches tall, “small, dark and elfin. . . low-key, genuine, modest and kind,” he always wore a baseball cap to cover his premature baldness. His father, twice hospitalised as an alcoholic, bullied and disparaged him.

O’Brien opposed the war in Vietnam and knew America couldn’t win. He felt profound lifelong guilt for not deserting to Canada when he was drafted in 1968 and for serving as an enlisted man in combat. He confessed that he “hated the war and the lack of good reason behind it, living with the knowledge I’m a coward for being here rather than pitting myself against it, any way possible.” His dangerous job as radio operator kept him at the front with his platoon. He would contact headquarters and call in helicopters to provide fire power and evacuate the wounded and the dead. His biographer writes that “O’Brien had to derive the grid coordinates from the map and then encode them with the daily code book before sending. Any misstep could send the helicopter to the wrong spot, possibly costing a life.”

O’Brien’s letters to his close friend Erik Hansen (born 1947), author of the first-rate travel books Stranger in the Forest (1988) and Motoring with Mohammed (1991), are the most revealing. He wrote to Hansen from Vietnam: “I’m trying like hell to ignore the red dirt all over me; and the flies, the dry heat, the depression that, for me, is always subsequent to the deaths. I’m not immune, and, careful as I am, there are too many mines for hope to keep you going.” His dangerously incompetent lieutenant had to be removed, his radio once protected his back from whizzing bullets, and he was lucky to have survived 13 months of combat—which inspired his best fiction –with only a slight shrapnel wound. He was horrified to see a dead Vietnamese child, and “never hated the Vietnamese—he pulled the trigger out of personal fear.” After 20 years in Vietnam, America suffered a humiliating defeat, having sacrificed 211,650 dead and wounded soldiers.

After the war O’Brien, a half-hearted graduate student in political science at Harvard, finally dropped out. He then worked as a reporter on the Washington Post. He smoked heavily, and when not writing he watched television, gambled in casinos, played ping pong and golf, and lifted weights. His phrase, “a 92-pound weakling”, came from Charles Atlas’ ad for body-building.

He married Ann Weller in 1973, and his simultaneous ten-year affair with Gayle Roby ended in 1989. Ann was either very imperceptive or very tolerant. Roby wanted children; O’Brien wouldn’t leave his wife and told Roby, “the problem with you is that you can’t want something, have it, and still want it.” He meant that she had him part time and had to be satisfied with that. In 1991 Ann complained: “You’re always distracted. If you don’t want to be with me, move out”—and he immediately accepted her challenge.

O’Brien had another simultaneous long-term affair with Kate Phillips, who visited Vietnam with him in 1994. When they returned to America, she broke with him after 15 years, which sent him into a deep depression. His biographer is discreet about the reasons for Phillips’ departure. O’Brien may have felt guilty about deceiving and leaving Ann, had casual affairs, was too absorbed in his writing and relived the agonizing nightmares of Vietnam.

In 1999 he took a teaching job at Texas State University in San Marcos, outside Austin, and taught there every other year from 1999 to 2012. In June 2001 he married his second wife, Meredith Baker, the daughter of a Protestant minister. Twenty years younger than O’Brien, she was tall and athletic, had bleached blond hair and was an amateur actress. He’d been unwilling to have children with Gayle Roby, but had two boys with Meredith. He was a good father, and both sons graduated from the University of Chicago. In 2017 he miraculously survived grave illnesses: pneumonia, acute gastritis, kidney and liver failure, impaired pancreatic function and the weight loss of 23 pounds.

An energetic self-promoter of his novels, O’Brien kept a keen eye on the competition, assiduously attended conferences, was interviewed scores of times and—recycling his anecdotes—took many 30-city book tours. He went to the Bread Loaf writers’ conference in Vermont for 14 years, first as a student—even after his first novel had been published—then as a teacher. He was a conscientious and encouraging instructor, enjoyed the excessive adulation and reaped the sexual harvest that came with the job.

He didn’t plan his work carefully but plunged ahead when the words flowed, then cut as many as 100 pages. He tended to cobble his novels out of previously published stories. After In the Lake of the Woods, his last major novel, “he announced the end of his writing career—there was nothing more to give, nothing else he wanted to do with his fiction.” Though that book was a great success, he felt suicidal and had an emotional breakdown during a bookstore reading. He found writing a “pleasureless chore,” but kept on composing as if he were on automatic pilot. Between In the Lake in 1994 and 2023, he published four inferior novels that damaged his reputation.

O’Brien’s biographer, Alex Vernon, graduated from West Point, saw combat in the First Iraq War and is now a professor of English in Arkansas. His book Peace Is a Shy Thing: The Life and Art of Tim O’Brien (St. Martin’s, 546p, $37) is competent and dutiful, but doesn’t achieve its full potential. It violates a cardinal rule of life-writing: the author must not include everything he’s found, but only the words that will interest his readers. He must be selective rather than exhaustive, analytical rather than descriptive. Vernon has done extensive research, but includes many trivial details. He’s interviewed 108 people, but has not extracted the vital information that makes his subject come alive. Vernon’s descriptions of O’Brien’s 13 months of war, a mixture of military records in Texas Tech and If I Die, are very repetitive. His pedestrian style includes long lists of names, many clichés, and irritating diacritical marks on Vietnamese words: Sài Gòn for Saigon.

Vernon’s long accounts of O’Brien’s mediocre fiction emphasise its composition, revisions and serialisation rather than its meaning. He writes that one story “limns the limits of imagination”. Vernon says that O’Brien “preferred short forceful titles,” which contradicts If I Die in the Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home and In the Lake of the Woods. Two errors have crept into the text: Gloucester is northeast of Boston, not in western Massachusetts; in Heart of Darkness a French (not a British) man-of-war fires shells into the bush.

Vernon should have said more about O’Brien’s financial earnings and magic tricks (Edmund Wilson had the same hobby), about his conversation and the emotional dynamics of his first marriage. Ann almost disappears from the text and the photos when Meredith takes center stage. The structure of this book is weak. Chapter 3 on Vietnam jumps ahead of the narrative. Chapter 17 on Juvenilia goes back to childhood. The epilogue focuses on the works and death of the Vietnam novelist Larry Heinemann rather than on O’Brien. The end of his life lacks dramatic interest. Vernon covers the last 22 years in only 40 pages; the last 7 years in 11 pages. At one point Vernon omits 11 years, from 2003 to 2014.

Vernon could have greatly strengthened his book by discussing the background and cultural context: the influence of Garrison Keillor’s Prairie Home Companion and Robert Bly’s Iron John, both by Minnesota contemporaries; a comparison of O’Brien’s novels to the fiction about a just war of Norman Mailer, Irwin Shaw and James Jones, and to the Vietnam novels of Michael Herr and Philip Caputo. He does not quote the best books on the Vietnam war, by Frances FitzGerald, Stanley Karnow and Neil Sheehan; does not discuss the best films on the war: The Deer Hunter, A Bright Shining Lie and Apocalypse Now, which portrays the fake body counts, prostitution, music, drugs and corruption that Vernon omits.

Vernon is perceptive about the impact of T. E. Lawrence’s The Mint on O’Brien’s account of his basic training. But he misses other important influences. The dying John Keats said his epitaph would be, “Here lies one whose name was writ on water.” O’Brien’s poem repeats, “[We] wrote our battle in the sand.” Thomas Hardy’s “The Man He Killed” is echoed in O’Brien’s story “The Man I Killed.” The plot of Arthur Miller’s All My Sons is repeated in America Fantastica where the “father-in-law’s shipbuilding shortcuts and bribes caused three ships to sink, killing a lot of sailors.”

Vernon is surprisingly weak on Hemingway, O’Brien’s main influence. Hemingway’s father hated the stories in his Paris-published pamphlet Three Stories and Ten Poems, not in his first book In Our Time. “Cat in the Rain” does not “reflect the father-son relationship”; Hemingway wrote about their relations in “Indian Camp” and “Fathers and Sons.” Vernon states, “the opening line of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms defies the journalistic dictum of establishing who, what, where and when.” But there’s no reason why his novel should follow this inappropriate dictum. He notes that in For Whom the Bell Tolls “Robert Jordan falls for a woman he calls ‘Rabbit’ who serves him rabbit stew.” In fact Jordan, more interested in sex than stew, calls her rabbit because it means “pussy” (conejo) in Spanish slang.

Vernon recognizes some influences. O’Brien’s Northern Lights, a spoof and parody of Hemingway, copies the last words of The Sun Also Rises: “Isn’t it pretty to think so?” In “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” the dying Harry dreams of being flown to safety on the mountain, “high and away to the only thing left visible, great, high, and unbelievably white in the sun.” In O’Brien’s The Nuclear Age the hero wants to be purely borne “off the edge of the earth and beyond the sun.”

But Vernon misses more important examples of Hemingway’s seductive style:

–Hemingway writes in Interchapter V of In Our Time: “There were pools of water in the courtyard. There were wet dead leaves on the paving of the courtyard.” O’Brien repeats, “There were Viet Cong in that hamlet. And there were babies and children. . . . There were twenty-seven bodies altogether.”

–Hemingway writes in Interchapter II, “Minarets stuck up in the rain.”

O’Brien repeats, “Bullets slashed out of the bushes.”

–Hemingway declared, in an ironic boast, “I beat Mr. Turgenev. I trained hard and I beat Mr. de Maupassant.” O’Brien said of contemporary writers, “Hemingway beat them cold, a one round knockout and he wasn’t in good shape.”

Invited to speak and write about Hemingway for a conference in 2015, O’Brien declared that he “saved my life and made me a writer again.”

In 1952 O’Brien’s mother had a mental breakdown and, like Hemingway, endured Electro-Convulsive Shocks at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. But Vernon does not explain the effects of his mother’s trauma on the six-year-old O’Brien. Hemingway’s shock treatments at the Mayo Clinic, nine years later in 1961, intensified his depression. The doctors discharged him, against the wishes of his wife Mary (who grew up in Minnesota), so he wouldn’t die in their hospital. He was then a complete wreck and looked like a decrepit old man. A week later he killed himself in Idaho. When I was interviewing Hemingway’s doctor, who defended his disastrous treatment, a lawyer rushed in to interrupt our conversation and evict me from the Mayo Clinic.

Jeffrey Meyers published Inherited Risk: Errol and Sean Flynn in Hollywood and Vietnam (2002), and discovered what happened to Sean Flynn after he was captured and disappeared in the jungles of Cambodia.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.