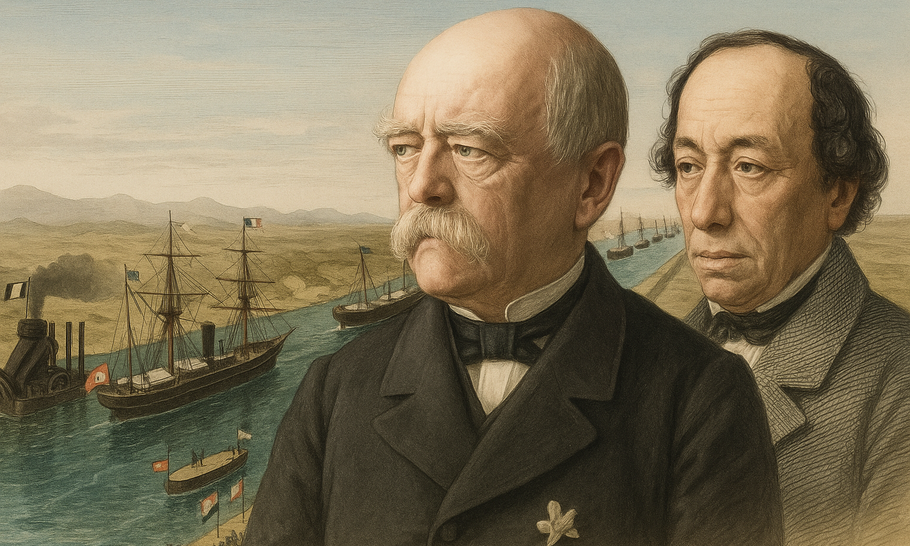

Bismarck, Disraeli and the Suez Canal

The procession of ships in the Suez canal for its opening. Benjamin Disraeli and Otto von Bismarck

On November 17, 1869, a seminal moment in world history occurred which has largely been forgotten. The Suez Canal was opened by Ishmail Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt. One onlooker prophesied that it would be “the artery of prosperity for Egypt and the world”. The other country that was certainly deemed likely to prosper, though, was France. The French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps had spearheaded the Canal project from its inception in 1854, in the teeth of British Prime Ministers such as Palmerston and Disraeli. The French were confident that their control of the Canal would disrupt British trade round the Cape of Good Hope. It gave them a crucial passage to India. Napoleon III – the monarchical embodiment of decadence – sent his wife Eugénie to the ceremony.

Yet less than a year later France was in a severe crisis. The Franco-Prussian War had broken out in July 1870. The proximate cause was the candidacy to the throne of Spain. Historians have usually laid responsibility for this war on Bismarck’s ambition to unite the German states and on Napoleon III’s cack-handed attempt at regaining the imperial grandeur of his namesake.

Recent studies by Karin Varley and Rachel Chrastil have given the Franco-Prussian War new prominence in the development of modern warfare and the formation of twentieth-century Europe. They highlight the impact of the war on the eastern Mediterranean, where Russian ambitions would buttress the tensions that broke out in 1914. The modern weaponry on show in 1870-71, and the unitary nationalism fashioned by the conflict, are seen to presage the World Wars. One thing that historians have left out of their accounts of the Franco-Prussian War, however, is the Suez Canal.

Britain stayed neutral in the war of 1870. Gladstone had won the election of 1868, partly on a policy of keeping out of foreign entanglements. In July 1870, just before the war broke out, the Foreign Secretary, Lord Clarendon, died, to be replaced by Lord Granville. On Granville’s arrival at the Foreign Office, the permanent secretary hilariously assured the new incumbent that he was ”not aware of any important subject I should have to deal with”.

That soon changed when Franco-Prussian relations deteriorated following the French refusal to accept a Prussian candidate being elected to the throne of Spain. In July 1870 Bismarck sent his notorious Ems telegram about a meeting between the King of Prussia and the French ambassador, edited to incite the French towards war. Bismarck realised that the Austrians – beaten by General Moltke’s Prussian military efficiency in 1866 – were unlikely to come to the aid of the French. Other German states sided with Prussia. The British looked set to continue in splendid isolation. Most commentators thought the French military, with its chassepot rifles and numerical superiority, could roll over the Prussians.

After only two months of fighting, France faced a total disaster. After defeats at Gravelotte and Wissembourg, the Emperor Napoleon III was captured at a huge set-piece battle at Sedan in early September. Strasbourg was besieged, Metz was taken. By late October, the Prussians and their German allies were besieging Paris.

The siege of Paris was the wonder of the journalistic world. In January 1871, 42 per cent of newspaper news around the globe was about the conflict. Parisians commented that they learnt the latest updates not with their own eyes but from copies of the New York Times. After Napoleon III was deposed, a Republican government took over in October, before being forced to retreat to Versailles. Paris was bombarded by Prussia and the humiliated Third Republic, led by Thiers, was forced to sue for peace. Britain was shocked: with only slight hyperbole, Disraeli told the House of Commons that the traditional diplomatic map of Europe had been “completely destroyed”.

The thread that links the Franco-Prussian War to the Suez Canal is the Bank of Rothschild. By the second half of the nineteenth century, the Rothschilds had become the most important financial family in Europe. In January 1871, Tiers had surrendered to the newly formed German Empire and the Treaty of Frankfurt was signed in May. The Germans demanded a war indemnity of 5 billion francs, with the proviso that their troops would not leave France until it was fully paid. They also annexed Alsace and Lorraine. Meanwhile Paris had been taken over by the revolutionary Commune in March. It held out until late May, when Republican troops crushed the Communards amid terrible bloodshed.

France was left racked by these events. Banks in Paris and London withheld credit across the globe. The expectation was that the payment would remove France’s supplies of gold and silver. However, with Rothschild assistance, the French payment of the war indemnity became one of the most astounding financial feats of the century. The government offered its citizens rentes, by which sovereign bonds could be bought to pay off the debt. The entire indemnity was paid to Bismarck by October 1873. What had been intended to destroy the French economy had, to some degree, buoyed it up.

Yet the defeat of France did have repercussions throughout the French Empire. In Algeria, around 800,000 revolted against the French. The depleted French army put down the Mokrani Revolt and instituted a new system of colonial rule. In Egypt, however, there was less recovery. British interests in north Africa only grew with the French defeat.

In The Global Merchants, Joseph Sassoon illustrates how families from outside Britain and outside the Establishment gained access to the highest chambers of power and society through their financial and philanthropic endeavours. The Sassoon family were one example, but the Rothschilds perhaps the greatest. Lionel Rothschild was a friend of Disraeli, and became the first observant Jew to sit in the Commons. When Disraeli returned to power in 1874, Rothschild had a remarkable proposal for him.

The Franco-Prussian War and the ensuing pressure of international banks had proved disastrous for outposts of European Empire. In 1873, The Economist (then edited by Walter Bagehot) published an essay: “The Fall in the Value of Money”. The French collapse had brought problems to Uruguay, Buenos Aires, Australia, and to Egypt. In 1873, the Egyptian government contracted a loan of £32 million from the Imperial Ottoman Bank. In October 1875, the Ottoman government partially defaulted on its debts.

Lionel Rothschild alerted Disraeli to the chance of buying up shares in the Suez Canal Company: this would inject British money into Egypt and secure greater control of a vital asset for Britain’s connection with India. Parliament was out of session when Disraeli took the decision on his friend’s solution. He borrowed £4 million (about £365 million today) from Rothschild’s bank to buy 45 per cent of the shares in the Suez Canal for Britain from the Khedive. It was essentially a ”gentleman’s agreement”, with very little documentation. Gladstone was outraged at the lack of Parliamentary consultation. The financial risk was large, but the funds were repaid to Rothschild’s in five months. Paris was aghast.

In the meantime, Lionel Rothschild had secured a highly dynamic asset for the British. The Egyptians were pushed further into the British orbit, and ambitions for colonial control would only grow more insidious. In 1882, the Anglo-Egyptian War secured control for London, to the disadvantage of Cairo, Constantinople and Paris. British troops took over the Suez Canal. In 1888, The Canal was declared a neutral zone under British control. For the French and the Egyptians, then, the events of 1869-75 were a perfect storm of military, financial and political disaster. None of it, however, was possible without the defeat of the French in late 1870 – and the credit crunch that resulted. Britain may have stayed out of the fighting in 1870-71. It could not, however, have ever stayed away from the ramifications of Bismarck’s war.

Are there modern parallels? In the twentieth century, historians often viewed the Franco-Prussian War as a “limited” conflict. Karine Varley highlights the drastic and global implications of Bismarck’s victory. Yet Britain was an accidental victor from what happened on the battlefield of Sedan. When international markets were halted and credit hard to come by, investors and politicians looked for a centre of gravity. They found it in London. Wars help urge on developments like this. In the aftermath of conflicts on European soil today, the victors might come from strange places. But a basic rule often holds. When power starts to fray, follow the money.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.