Dante’s notes from underground

Close-up of face profile'detail about knick knack depicting Dante Alighieri in plaster on a black background (Shutterstock)

Joseph Luzzi’s learned and lively Dante’s Divine Comedy: A Biography (Princeton) describes Dante’s profound influence on Western culture as the poet leads readers per ignem ad lucem (through fire to the light). It shows how the poet was viewed differently throughout the centuries: “Dante as champion of the vernacular in early Italian literature, Dante as religious heretic during the Inquisition, Dante as literary hero for the Romantics, Dante as formal innovator for the Modernists and Dante as religious visionary for modern-day popes.” Yet Dante also had formidable enemies. Petrarch, jealous of Dante’s fame, mocked him as a dialect love poet and placed him with poetic mediocrities. Voltaire called the Commedia, which broke all the strict literary rules of the 18th-century, a “poetic monster”.

Instead of writing in Latin, Dante used Tuscan Italian and made it the dominant language of his country. But dialects remained strong in the peninsula. Luzzi writes that “as late as the nineteenth century, Milanese nobles traveling to Sicily were mistaken for Englishmen, so incomprehensible was their language to the locals.” In Lampedusa’s The Leopard (1958), when the north Italian Chevalley travels to Sicily to invite Prince Fabrizio to join the new Italian Senate in Turin, people can’t understand him.

In 1302 Dante was pronounced guilty of corruption and exiled from Florence on pain of death. Other famous literary exiles include the Latin poet Ovid, Voltaire, Byron, Victor Hugo and the Italian novelist Carlo Levi, as well as Thomas Mann and all the Jewish exiles from Nazi Germany. Dante inspired three other modern writers who suffered from political oppression: the Italian communist Antonio Gramsci, who died in Mussolini’s Regina Coeli (“Queen of Heaven”) prison, a bitterly ironic echo of Dante’s Beatrice (Queen of Paradise); the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, who died of typhoid fever en route to the Gulag; and the Italian author Primo Levi, a survivor of Auschwitz, who quoted Ulysses’ fatal last line: “Until the sea again closed over us.”

Primo Levi

Dante’s most memorable lines are:

Lasciate ogni speranza voi ch’entrate (Abandon all hope you who enter here; a suitable motto for a Nazi extermination camp);

Nessun maggior dolore che ricordarsi del tempo felice nella miseria (There’s no greater pain than to remember happy times in misery);

E’n la sua voluntade è nostra pace (In His will is our peace);

L’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle (The love that moves the sun and the other stars).

Many of his lines have been echoed by modern writers: “uscimmo a riveder le stelle” (we came forth again to see the stars) influenced the aria in Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca: “e lucevan le stelle” (the stars were shining brightly). An echo of Dante’s “selva oscura” (dark wood) recurs in Robert Frost’s “Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening”: “The woods are lovely, dark and deep.”

In concise dramatic dialogues Dante reveals the personal histories and confessions of the sinners he meets in his journey through Hell. The eternally damned can talk to a man from the real world and achieve a temporary respite from their tortures. Dante’s persona, immune from the torments they suffer, naturally sympathizes with them. In Canto XV his former teacher, the renowned intellectual Brunetto Latini, is condemned to run naked beneath a hail of fiery rain in the Circle of the Sodomites. Dante the poet has placed Latini in Hell, but Dante the pilgrim, surprised to find him, asks: “Are you here, ser Brunetto?”

In Canto XXVI Ulysses is placed in Hell for persuading his loyal companions to accompany him on a doomed voyage. He’d urged them to follow the sun, to explore unknown regions and to “pursue virtue and knowledge.” But his ship, attacked by a whirlwind, was wrecked and his crew drowned when the sea closed over them. Like Pip in Moby-Dick, only Ulysses survived to tell the tale.

In Canto V the violent whirlwind is suddenly hushed—a meteorological event like God parting the Red Sea for Moses—so Francesca da Rimini can tell her poignant story. Murdered by her jealous husband, she’s punished again after death. When reading the tale of Lancelot’s guilty love for King Arthur’s wife Guinevere, Paolo and Francesca are overcome by “love that is quickly kindled in a gentle heart.” When Lancelot kisses his beloved in the story, the eyes of Dante’s lovers meet, their faces grow pale and Paolo kisses her. After that, they reenact their illicit love instead of reading about it. But Francesca pleads, in the language of courtly love, that they could not resist their feelings and were not responsible for their overwhelming passion. In Hell they are bound together on the whirlwind, a striking metaphor for falling in love, but not on earth as they had intended.

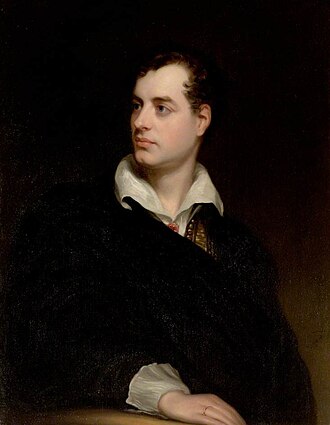

Lord Byron’s The Prophecy of Dante (1821), written in Dante’s terza rima, portrays the themes of “literary heroism, self-exploration and artistic endurance in the face of strife.” Byron describes the moment when the doomed Paolo and Francesca begin to kiss, stop reading and become lovers:

When we read, the long-sighed-for smile of her,

To be thus kissed by such devoted lover,

He, who from me can be divided ne’er,

Kissed my mouth, trembling in the act all over:

Accurséd was the book and he who wrote!

That day no further leaf did we uncover.

Portrait of Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips, c. 1813

Francesca, who blames the Arthurian author for inciting them, may be in Hell. But for Byron she is a heroine who inspires pity, sympathy and admiration. Both Ulysses and Francesca are true to their passions, act from idealistic motives and seem to be punished by Divine Will with excessive cruelty. It’s amazing that only 22 lines of Dante’s poetry could have such a powerful and permanent impact.

In Inferno, time stops and the sinners are forced to continue their punishment forever. They can’t escape from pain through death because they are already dead. Luzzi notes that “human time resurfaces in Purgatorio, after the static temporal realm of Inferno, where sinners exist in an eternal now, nailed forever to the cross of sins that they repeat forever.” In Purgatorio, the itinerant souls try desperately to bridge the tremendous distance between sin and salvation.

Luzzi writes most interestingly about John Milton, Mary Shelley, T.S. Eliot and James Joyce. He notes, “as a lifelong reader of Dante’s work, Milton almost certainly would have pondered the Dantesque notion of free will as God’s chief gift to humankind.” In Paradise Lost (1667), Milton writes that Adam was “Sufficient to have stood though free to fall.” But Adam, not strong enough to resist Satan, was doomed to fall and pull down all mankind with him.

“Both the Canto of Ulysses and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818),” Luzzi notes, “are about impassable borders: in Dante, the Strait of Gibraltar crossed by Ulysses and his men represent the end of the known world. For Shelley, the icy landscapes where Victor Frankenstein follows the monster represent that mix of beauty and terror central to Romantic aesthetics.”

Mary Shelley by Richard Rothwell (1840–41)

Eliot observed of The Waste Land (1922), “Dante had the most persistent and deepest influence upon my own verse. He expresses everything in the way of emotion, between depravity’s despair and the beatific vision, that man is capable of experiencing. Dante and Shakespeare divide the modern world between them, there is no third.”

Dante was James Joyce’s favorite writer. In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) he wittily calls Dante’s unattainable Beatrice “the spiritual heroic refrigerating apparatus, invented and patented by Dante Aligheri.” Dante himself is the model for Joyce’s emotional alienation and defensive exile.

Dante’s poem has been debased in our time. A hot sauce is named Inferno, and the circles of Hell are compared to “the local motor vehicles office and megastore shopping aisles, to online dating and passenger-jet seating. His name appears on olive oils, wines, even toilet paper.” Ascending from modern Hell to Heaven, Luzzi notes that though Dante had bitterly condemned five corrupt and power-hungry popes, “the greatest indicator of how Dante’s Commedia has been transformed from the bane of the Spanish Inquisitors to the darling of religious thinkers throughout the world is its reception by a group that Dante represented with venomous ink: the popes.” In modern times his poetry has been embraced by Pope Paul VI, the intellectual Pope Benedict XV and the current Pope Francis.

Luzzi’s book, not comprehensive and inevitably selective, does not mention music: Franz Liszt’s Dante Symphony (1857), Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s symphonic fantasy Francesca da Rimini (1876) and Sergei Rachmaninoff’s opera Francesca da Rimini (1906). And he does not discuss Dante’s influence on the art of Francisco Goya, William Blake and Gustav Doré. The dust jacket of this work reproduces Eugène Delacroix’s superb painting The Barque of Dante (1822), and Luzzi analyzes Botticelli’s illustrations to The Divine Comedy: “Dante’s punishments are all there in Botticelli’s Map (1495), represented in painstaking clarity. But because of the order and balance of his images, the fire and brimstone of Inferno feels muted, its dark energies absorbed by the pristine logic of the Florentine’s artist’s intention to detail and expert rendering of space. In Botticelli’s illustration, Ulysses and his companion, the fierce Diomedes, merely appear as fleeting profiles sandwiched in between the waves of flame that cover the parchment, their personalities swept away by the tidal force of Botticelli’s line.”

Luzzi’s book includes a fuzzy reproduction in the text of Domenico di Michelino’s Dante Holding the Divine Comedy in Florence (Florence: Duomo, 1465), but he does not discuss this great painting. Dante, a tall, thin, narrow-faced, sharp-featured figure, wears a long red robe and cap and is crowned with a poet’s laurel. He dominates the center of the painting and proudly displays an open copy of his book. The light radiating from this volume illuminates the Duomo and the high walls and towers that exclude him from his native Florence. On the left, beneath high jagged rocks, black, horned, spear-carrying demons drive the naked sinners into the flames of Hell. The circular high mountain of Purgatory looms up behind Dante as tiny naked figures, guided by a winged angel seated before a golden door, laboriously ascend the steep slopes and search for salvation. At the very top Adam and Eve, next to the Tree of Knowledge, urge them on.

Another enemy of Dante, the Dominican friar Guido Vernani, had condemned his religious beliefs and in 1327 called his book “the devil’s vessel.” Luzzi’s 10-page account of this attack is far too long and boring. It would have been more interesting and valuable to discuss important modern works that were profoundly influenced by Dante, including Arthur Rimbaud’s poems Une saison en enfer (1873) and Henri Barbusse’s novel L’Enfer (1908). Ezra Pound’s Cantos (1915-62) was modeled on The Divine Comedy and contained many allusions to Dante, and a whole book has been published about the poet’s influence on Pound. In History (1973) Robert Lowell wrote a long poem on Brunetto Latini and five sonnets on Dante, including a translation of the lines on Paolo and Francesca.

Malcolm Lowry conceived three of his novels as a trilogy modeled on Dante’s Commedia, beginning with Under the Volcano (1947) as the Inferno. Geoffrey Firmin, the damned anti-hero, declares “Hell is my punishment. My natural state.” He is paying for his wartime sins when Germans captured by his ship were thrown into the fiery furnace, symbolized in the book by the towering volcano. Firmin lives among the deceased on the Day of the Dead and the novel is filled with echoes of Dante. Chapter 6 begins with a fractured quotation from Dante’s opening lines: “Nel mezzo del bloody cammin di nostra vita mi ritrovai in . . . Hugh flung himself down on the porch daybed.”

Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (1956) uses Dante’s scholastic philosophy, fearful punishments and circles of Hell as the foundation of his own poem to heighten yet control the personal guilt and terror in his frenzied lamentation. A star performer of his own work, Ginsberg emphasised the agonised howl in Howl. As he chanted the poem and it leaped off the page, he made his ecstatic audience understand how Dante’s Inferno deepens the intellectual content, tightens the structure and enhances the theme of his greatest and most poignant poem.

Anna Akhmatova, who had an aquiline Dantean beak, wrote an intensely personal “Dante” in 1936 during the most horrible years of the Moscow Show Trials:

He did not return, even after his death, to

That ancient city he was rooted in.

Going away, he did not pause for breath,

Nor look back. My song is for him.

Torches, night, a last embrace,

Fate, a wild howl, at his threshold.

Out of hell he sent her his curse

And in heaven could not forget her.

But never in a penitential shirt did

He walk with a lighted candle and barefoot

Through beloved Florence he could not betray,

Perfidious, base, and self-deserted.

Akhmatova suffered a terrible internal exile under Stalin, who executed her first husband and condemned her son and second husband to long years in the Gulag. She identifies with the poet’s exile from his beloved Florence for his political beliefs and with his stoical refusal to look back (unlike Lot’s wife). She then imagines his suffering and compares it to her own. As her family is torn from her embrace, Dante seems to cry out to her from hell and heaven. Like Akhmatova, Dante remained courageous. He refused the offer to return if he publicly repented and never begged forgiveness from the evil city that had betrayed him.

Akhmatova in 1922 (portrait by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin)

Jeffrey Meyers will publish 44 Ways of Looking at Hemingway with LSU Press in the fall of 2025.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.