Duchamp, Cage and Katabasis

Composer John Cage, 23 June 1988 (image created in Shutterstock)

Several years ago a DADA Movement exhibition was staged in the Pompidou Centre, Paris. The work of Marcel Duchamp took centre stage. One of the exhibits was a chess set designed by the Master himself, a set on which I had previously personally played while visiting Alexina “Teeny” Duchamp (Marcel’s widow) at her chateau just outside the capital.

Spotting the familiar set, I approached and leaned towards it to gain a closer look. At this point a legion of gendarmes leapt out of hiding and ordered me to retreat from the holy relic of Duchampian art. Fifteen minutes later, after we had left the gallery, a lunatic armed with a hammer attacked the set, inflicting some damage — which was, fortunately, easily reparable.

This incident sprang to mind when I saw the attack launched over the weekend of January 27 against Da Vinci’s masterwork, the Mona Lisa. Eco-protesters hurled pumpkin soup against the bullet-proof glass protecting the immortal smile. What struck me was the complete absence of official response, no security guards, no leaping gendarmes from hidden arrases. The protesters were even given the time to make a statement extolling whatever Gallic grievance had motivated them to launch their futile onslaught in the first instance.

An evil thought then struck my mind. What if these attacks were not so much manifestations of an Arrabalesque theatre of panic, more an outlier of théâtre de complicité. Could the French galleries concerned have known in advance of the attacks, even encouraged them for publicity purposes, only intervening when an unscheduled interloper, such as myself, threatened to get too close to the exhibit?

I never got to know Marcel Duchamp, though I certainly knew his widow, Teeny. Indeed I once had the pleasure of watching a game between her and the artist Barry Martin. It was played in her chateau at the bottom of a staircase, which was adorned on the way down by a copy of Duchamp’s primary homage to Cubism, Nude Descending a Staircase.

J. F. Griswold: The Rude descending a staircase (Rush-Hour at the Subway). The New York Evening Sun, 20th March 1913.

This was the infamous No.2, first not shown at the “open” 1912 Salon des Indépendants in Paris, with associated scandal attached. It was eventually, and somewhat infamously, exhibited at the Armory Show in New York, the following year.

Teeny Duchamp’s chateau also contained a huge blue bath in the shape of a hippopotamus, designed by Nicki de St Phalle exclusively for the Duchamp’s’ close friend, the avant-garde composer John Cage. I also knew Cage, and played chess against him many times. He once told me that he had learned chess in order to communicate osmotically with Duchamp, without having to ask clumsy questions of the Master, such as: “What did you mean by …?”

With Barry Martin, I once organised Cage’s birthday party at the Chelsea Arts Club. The cake was baked in the shape of Duchamp’s notorious Fountain — an inverted urinal! When Cage died in 1992, I was invited to attend “Rolywohlyover”, a celebration of his life and work at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

Cage’s last collaboration with Duchamp was a performance piece consisting of a musical chess game, fittingly called “Reunion”; Teeny acted as referee. The moves triggered a series of electronically generated sounds. That game aside, no record survived of the numerous games of chess played between these two giants of avant garde art… until now.

I have recently had the pleasure of advance sight of a game played in New York in 1966 — possibly the only surviving recorded encounter between Cage and Duchamp. It will feature in a forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Duchamp’s games, a comprehensive compendium being edited by my friend, Adam Papier Black. I am grateful to Donna Savage and Larry List for permission to quote extracts.

The game score is recorded on Marshall Club stationery. This, of course, does not incontrovertibly confirm the famous Manhattan club as the venue, but it is an interesting proposition: that Duchamp may have brought Cage to visit and experience in club form, what étant donnés had become artistically for Duchamp, namely a personal sanctuary,

The Marshall Club is a comfortable town house in Greenwich Village. It is an imposing property, personally bequeathed by the great Frank Marshall, grandmaster and US Champion 1909-36, to its membership. Unlike many other famous clubs, the Marshall is permanently established, not insecurely peripatetic.

The game features two memorable moves that are the inspiration behind today’s column. First, we shall take a look at their opening, a refreshing rescue from stereotyped lines that computers churn out on demand. The second is the use of the seemingly incongruous move Nh1. This features in the main Nimzowitsch game, a game a good forty years prior to the Cage-Duchamp encounter.

Marshall Club, informal game

John Cage vs. Marcel Duchamp

½-½, circa 1966

1.e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. h3!?

A remarkably sensible and effective means of deviating from theory. After the perfectly conceivable, 3… Nf6 4. Nc3 a6 5. d4 cxd4 6. Nxd4, we have arrived at the starting point for the Adams attack in the Najdorf variation of the Sicilian defence. I too once encountered 3. h3 which I met with 3…Nbd7

3… Bd7

Duchamp’s signature move in several opening systems eg. as White in the Nimzo-Indian. Even now, transposition is possible to recognised Sicilian systems, for example after, 4. c3 Nf6 5. Bd3, a delayed Alapin. Another version with 5. Qc2, featured in the 2009 World Cup rapidplay draw between Svidler and Movesian. 5. d3, played twice in a 2020 rapidplay match between Aronian and Vachier-Lagrave. In 2022, Shevchenko won with black against Szpar, after essaying 5… Bc6!?

As noted above, I have also had the opportunity to confront this innovative sidestep. In one of my more successful tournaments, in good form, I powered to a performance of six wins from six games.

A. Harris vs Raymond Keene (King’s Head)

Middlesex Team Championship, May 1982

Sicilian Defence

1.e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. h3 Nf6 4. Nc3 Nbd7 5. d4 cxd4 6. Nxd4 a6 7. Bd3 e6 8. O-O b5 9. b4 Bb7 10. Nf3 Qc7 11. Qd2 Nb612. Bb2 Be7 13. a4 bxa4 14. Nxa4 Nxa4 15. Rxa4 Nxe4 16.Bxe4 Bxe4 17. b5 Qxc2 18. Qxc2?

Unnecessary. White must seize the little counterplay available, and follow up 17. b5 with 18. Rxa6 – exploiting the fact that Black has yet to castle.

18… Bxc2 19. Rxa6 Kd7 20. Rxa8?

It was better to play 20. Bxg7 first, so that there is a tempo in attacking the h8-rook.

20… Rxa8 21. Bxg7 Bd3 22. Ra1

There is no way for White to defend his remaining asset, the b-pawn, but a better finesse was with: 22. Rd1 Be2 23. Ne5+ Ke8 24. Re1 Bxb5 25. Ng4, when White is busted but less busted than in the game.

22… Rxa1+ 23. Bxa1 Bxb5 24. Bg7 e5 25. Bh6 f6 26. g4 Ke6 27. Nh4 Bd3 28. f3 d5 29. Ng2

Prosaically, 29. Kf2 would have been preferable, but even then, it would not alter the inevitable outcome.

29… Bc5+ 30. Be3 d4 31. Bd2 f5 32. Ne1 Be2

- Kf2 d3+ 34. Be3 d2 35. Kxe2 dxe1=Q+ 36. Kxe1 Bxe3 37. Ke2 Bg5 38. Kd3 f4 39. Kc4 Bh4 40. Kd3 Kd7 41. Ke2 Kd6 42. Kd2 h6 43. Ke2 Kc5 44. Kd2 Kd4 White resigns. 0-1.

This concludes our quick overview of 3. h3 in the Sicilian Najdorf variation. And now let us briefly return to the game between Cage and Duchamp, where Duchamp as Black has constructed a mighty position.

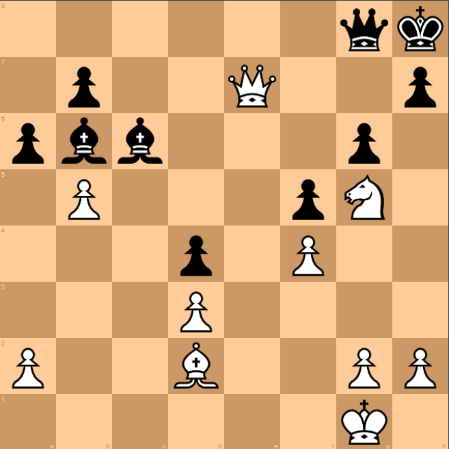

position after 21… O-O

Cage vs. Duchamp

22.Rd3 Rxd3 23. Kxd3 Rd8+ 24. Kc4 a5 25. Bb3 g6 26. Rd1 Rxd1 27. Bxd1 Be1 28. Nh1? Can it ever be correct to commit such an abject and extreme Katabasis as moving a knight to that Ultima Thule of the chessboard, the square h1? It worked here. Although Duchamp missed winning chances, this game was eventually drawn.

Cage’s 28 Nh1 was definitely not a retinally attractive move. But perhaps not much worse than 28. Kb5 or Ne2. As we will see, Aron Nimzowitsch, the great chess writer and strategist, a hero and role model for Duchamp, had a penchant for paradoxical moves such as Nh1, but only in the context of enhancing middlegame tension, rather than manning a last ditch endgame barricade. Here is the master game between Nimzowitsch and Rubinstein:

Aron Nimzowitsch vs Akiba Rubinstein

Dresden, rd 5, (best game prize)

April 9th, 1926

1.c4 c5 2. Nf3 Nf6 3. Nc3 d5 4. cxd5 Nxd5 5. e4 Nb4 6. Bc4 e6 7. O-O N8c6 8. d3 Nd4 9. Nxd 4cxd4 10. Ne2 a6 11. Ng3 Bd6 12. f4 O-O 13. Qf3 Kh8 14. Bd2 f5 15. Rae1 Nc6 16. Re2 Qc7 17. exf5 exf5

18.Nh1

Cerebrally…A wonderful idea. White has in mind the manoeuvre Nh1-f2-h3-g5, in conjunction with Qh5, as a method of assaulting the position of Black’s king. When I first read Nimzowitsch’s My System, I was so impressed by this game that I deliberately created situations in my next few games where the move Ng3-h1 was possible, in the belief that this mystical retreat would somehow result in a miraculous increase of energy in my position, irrespective of whatever else may have been happening on the board at the time. More objectively, the simple, banal, obvious and logical 18. Rfe1 would have been stronger.

18… Bd7 19. Nf2 Rae8 20. Rfe1 Rxe2 21. Rxe2 Nd8 22. Nh3 Bc6 23. Qh5 g6 24. Qh4 Kg7 25. Qf2

Another brilliant idea. The threat to the d-pawn forces Black to withdraw either his queen or his king’s bishop from the defence of his kingside.

25… Bc5 26. b4 Bb6 27. Qh4

Back again and with redoubled strength.

27… Re8

Or 27… Rf6 28 Ng5 h6 29 Nh7 +-

28.Re5! Nf7

If 28… Rxe5 29. fxe5 Qxe5 30. Qh6+ or 28… h6 29. g4 hxg4 30. f5 Qxe5 31. f6+ Qxf6 32. Qxh6 mate. These beautiful variations are just an indication of what Nimzowitsch saw.

29.Bxf7 Qxf7 30. Ng5 Qg8 31. Rxe8 Bxe8 32. Qe1!

A decisive change of front.

32… Bc6 33. Qe7+ Kh8 34. b5!!

Who would expect the death-blow to come from this quarter? If Black plays 34..axb5 he is mated as follows: 35. Ne6 h5 36. Qf6+ Kh7 37. Ng5+ Kh6 38. Bb4! In view of this, Rubinstein elects to surrender a piece but that too is obviously without hope.

34… Qg7 35. Qxg7+ Kxg7 36. bxc6 bxc6 37. Nf3 c5 38. Ne5 Bc7 39. Nc4 Kf7 40. g3 Bd8 41. Ba5 Be7 42. Bc7 Ke6 43. Nb6 h6 44. h4 g5 45. h5 g4 46. Be5 Black resigns 1-0

Ray’s 206th book,

Chess in the Year of the King

, written in collaboration with Adam Black, appeared late last year. Now his 207th, “

Napoleon and Goethe: The Touchstone of Genius”

has materialised, just in time to complement Ridley Scott’s Napoleon.

Both books are available from Amazon and Blackwell’s.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.