Edmund Wilson and Allen Tate: a fierce friendship

The ideological conflicts of two literary titans, Edmund Wilson (above) and Allen Tate, represent a crucial division in modern American thought and culture. They clashed between social context and New Criticism in literature, between North and South in history, between progressive and reactionary in politics, between atheist and Catholic in religion. Wilson was slightly older than Tate and helped launch his career, but he had an insider ’ s advantage in New York when the two intensely ambitious men competed for literary power and fame. They reviewed each other ’ s books, but carefully undercut their praise with incisive criticism. In the 1920s they had similar literary values and became friends, but the prevailing Left-wing politics of the post-Depression 1930s brought their personal and cultural conflicts into sharp focus. They finally quarrelled, insulted each other and drew apart, as friends often do in contentious old age.

These long-lived contemporaries, Wilson (1895-1972) and Tate (1899-1979), had a great deal in common. They were well educated in the classics, and close friends of the Princeton graduate and poet John Peale Bishop. Prolific men of letters in many genres, they wrote poems, plays and novels as well as criticism, history, biography, memoirs and polemics. They were influential editors, generous to other writers and well placed to help attractive young women succeed.

Both men, wobbling between being heavy drinkers and certified alcoholics, had serious financial problems and bitter fights with the IRS (Internal Revenue Service). Though often short of cash, Wilson had four marriages, Tate had three and divorced his first wife twice. Tate married two poets and a nun, Wilson trumped him with an actress, socialite, novelist and aristocrat. Wilson had three children, Tate topped him with four.

Wilson ’ s second wife and Tate ’ s twin son died in freak accidents. Margaret Canby fell down a staircase, the infant Michael Tate choked on a toy telephone. Both included prominent writers in their impressive seraglios. Wilson had liaisons with the poets Edna St. Vincent Millay, L é onie Adams and Louise Bogan as well as the diarist Ana ï s Nin and the film critic Penelope Gilliatt. Tate had affairs with the poets Laura Riding and Jean Garrigue, the novelists Katherine Ann Porter and Elizabeth Hardwick, and the concert pianist Natasha Spender. (I have written about Tate and his women here .)

Their differences were even more significant and turned the old friends into intellectual enemies. Wilson, descended from the New England puritans and the seventeenth-century minister and author Cotton Mather, was the son of the attorney-general of New Jersey and friend of President Woodrow Wilson. Tate, descended from Kentucky plantation owners, was the son of a heavy drinker, pouncing philanderer and active racist, who repeatedly failed as a small businessman. Wilson was educated at Princeton; Tate was educated under John Crowe Ransom at Vanderbilt in Nashville. “ Bunny ” Wilson, who kept his childhood nickname, was plump; Tate, a dandy with moustache, bowtie and cane, was cadaverously thin.

Tate studied violin in a conservatory; Wilson had no interest in music, though he liked popular culture and was an amateur magician. After caring for wounded and mutilated soldiers in a military hospital in France in World War I, Wilson strongly opposed all wars, even the one against the Nazis. Tate had been too young to serve. Wilson, a fluent and independent professional writer who poured out his work with full-throated ease, disliked teaching. Tate, a college professor at Sewanee and the University of Minnesota, sometimes suffered from writer ’ s block. He couldn ’ t finish the planned sequel to his only novel, The Fathers (1938), and dried up for long stretches without writing poems.

Wilson was interested in the biographical and cultural background of the writers he analysed; Tate was an apostle of the fashionable New Criticism, which taught critics to ignore the cultural context and focus exclusively on the text. They had antithetical attitudes about the Civil War, slavery and racial equality. Wilson, a Northern liberal, made strenuous efforts to break away from the values and prejudices of his class, and identified with the underdog. Tate clung desperately to his conservative Southern values throughout his life. He was an ante-bellum reactionary who dreamed of a Southern victory in the War Between the States and a return to the genteel traditions of the Old Plantation, including the estate that had been owned by his family.

Wilson, a more profound thinker than Tate, had a wider range of interests and greater knowledge of languages, including Latin, Greek, French, Italian, German, Cyrillic Russian, Semitic Hebrew and Finno-Ugric Hungarian. Beginning with Paul Val é ry and Marcel Proust, Wilson wrote about many foreign authors. Tate wrote mainly about American and English poets. In 1935 Wilson traveled for five disillusioned months in Russia, studied communist doctrine and spent six weeks recovering from scarlet fever in a primitive Odessa hospital. He then wrote To the Finland Station (1940), a study of socialism and communism, with portraits of Lenin and Trotsky. Tate despised Soviet life and ideology. Wilson traveled to Haiti and Israel, and sympathised with the Jews. He wrote about the biblical Dead Sea Scrolls, the Zuni Indians in New Mexico and the Iroquois in New York, and the culture and politics of Canada. Tate, except for his lover Laura Riding, had no interest in Jews or minority cultures.

Wilson disapproved of Tate ’ s vain display when he wore three-piece suits with his Phi Beta Kappa key strung across his vest. Wilson lived on Cape Cod and his ancestral home in upstate New York. Tate, obsessed with the bluegrass and bourbon of Kentucky, wound up in the frozen wasteland of Minnesota. Wilson ’ s fourth wife was devoted to him and his last marriage ended happily. Tate ’ s third wife, an ex-nun, hated him and treated him harshly during his long last illness. Both men were keenly interested in literary news and gossip, and asked (like King Lear) “ Who loses and who wins; who ’ s in, who ’ s out. ” In Nashville, two days before he died, Tate asked Stephen Spender about the current reputation of his fellow-poet Louis MacNeice.

Wilson could be combative, but Tate was more waspish, vituperative and manipulative. The poet John Berryman, noting Tate ’ s ambivalent personality, called him “ a very generous and corrupt man, open-hearted, wily, spiteful.” In the fall of 1949 Berryman ’ s wife Eileen Simpson heard that Tate was “ an operator, who in recent years (a time when he had not been able to write poetry) had become divisive and jealous over the success of others.” Tate ’ s colleague Walter Sullivan emphasised his destructive streak: “ Not even his own self-interest could deter Allen ’ s characteristic impulse toward confrontation and dispute.” His poetic disciple Randall Jarrell defined Tate ’ s greatest fault, which intensified his clash with the more flexible Wilson, as “ a defect of sympathy in the strictest sense of the word, a lack of ability to identify himself with anything that is fundamentally non-Allen.

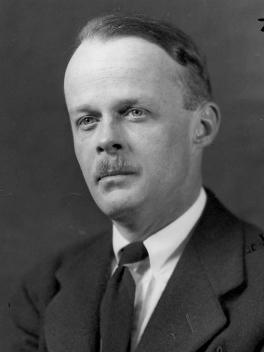

Tate (pictured above) was the editor of the highbrow, small-circulation, Southern-oriented Fugitive journal in provincial Nashville, and when he came to New York in 1924 the serial seducer worked for the appropriately-named Climax publishers. Wilson, still in his twenties, was a well-respected and influential editor at Vanity Fair, the Dial and the New Republic. Though both men were quite short, about five feet, six inches, Tate ’ s biographer Thomas Underwood writes that he “ was a bit intimidated by Wilson, who seemed both physically striking and intellectually threatening.” The struggling Tate had recently married the poet Caroline Gordon, and Wilson arranged for the young couple to get an emergency grant of $250 from a writers ’ relief fund.

In 1923 Tate had sent poems to Wilson at Vanity Fair. Wilson rejected them, but encouraged Tate by saying: “ I look forward to something extraordinary from you. But do try to get out of the artistic clutches of T. S. Eliot.” Two years later he told Tate that “ Mr. Pope” and “ Death of Little Boys” are your best poems: “ You have a very curious quality, not only a gift of imagery but a beauty and a ‘ strangeness ’ which makes me willing to bet on your future.” Tate, a better poet than Wilson, could afford to flatter his competitor. In 1929 he returned the compliment by puffing Wilson ’ s rather commonplace verse: “ Edmund Wilson has written some of the most accomplished poetry of our time.”

The first strains of discord appeared in December 1926 when Tate and the critic Malcolm Cowley got angry about Wilson ’ s essay “ Poe at Home and Abroad”. They felt it was based on their conversations with Wilson, who had appropriated their thoughts. Tate angrily told Cowley that “ Wilson ’ s shameless exploitation of the economic value of an idea was really humiliating”. But Wilson had his own thoughts about everything, and it ’ s unlikely that he took his ideas from Tate, who believed that he owned Poe.

Four years later Tate attacked Wilson ’ s review of one of T. S. Eliot ’ s major poem s: “ Edmund Wilson ’ s review of ‘Ash Wednesday ’ seems to me to be very unsound; it ends up with some very disconcerting speculation on Eliot ’ s private life which has no significance at all.” In fact, Wilson was right to oppose Tate ’ s narrow-minded critical dogma. He was one of the first to see that Eliot ’ s poems, despite his high-minded disclaimers, were intensely personal and that the autobiographical elements had great significance. The Waste Land included the speech of his deranged wife Vivien and alluded to his own nervous breakdown.

Tate thought Wilson was an “ excellent man and critic” when he praised Tate ’ s work, but was not so excellent when he criticised it. Wilson ’ s March 1928 review of “ The Tennessee Poets ” irritated Tate by alluding to Eliot ’ s influence, and by undermining his praise with serious qualifications and degrading comparisons. Tate ’ s great skill, it seemed, was merely decorative: “ even where Mr. Tate is imitative he possesses a strange originality, a special vein of macabre imagination . . . .Though, line for line, these poems are amazing, they seem, in some way, as wholes, to lack emphasis, to fail of cumulative effect. . . . [They] are like elaborate oriental ornaments which have been produced at an immense expense of materials, patience and cunning skill.” Still, in October 1928, Wilson told their mutual friend John Peale Bishop that Tate “ has become a great friend of mine.” Despite their quarrels, the men were always eager to meet for literary gossip and stimulating talk.

Wilson was a brilliant and generous critic. He introduced Hemingway to America in 1924 and to Yeats, Joyce, Eliot and Gertrude Stein as well as Val é ry and Proust in Axel ’ s Castle (1931). He encouraged his third wife, Mary McCarthy, to write fiction, revived Scott Fitzgerald ’ s reputation in the 1940s and launched Vladimir Nabokov ’ s career in America. In 1947 he sent Nabokov ’ s novel Bend Sinister to Tate, who published it at Henry Holt.

Tate, the mentor of Robert Lowell and Randall Jarrell, moved easily from Lowell ’ s Lord Weary ’ s Castle to Wilson ’ s Axel ’ s Castle . Before he became testy with Wilson, he perceived the major theme in Wilson ’ s masterpiece: the alienation of the modern writer. In his July 1931 review in Hound and Horn, he observed: “ Mr. Wilson is the first American critic to formulate a comprehensive philosophy of French Symbolism as it has affected writers in English.” He praised “ Wilson ’ s sensitive and finely modulated prose style, the emotional subtlety of his insight into the sensibility of his six writers,” and called the book “ a brilliant history of the increasing cross-purposes of the artist and his industrialised society. ” Speaking of both Wilson and himself, Tate predicted their impending conflicts, “ though being of the same generation in time, we are of such remote spiritual generations that we shall seem very obscure to each other.”

Wilson agreed that he and his friend and contemporary were intellectually opposed, and told Bishop, their mutual go-between and Father Confessor, “ Tate is falling foul of everybody of his own generation, charging them with romanticism, impressionism, Bohemianism, and all the stock crimes . . . of people who produced literature to be guilty of. He has buried us all alive.”

In May 1930, seven months after the Wall Street Crash that began the Great Depression of the 1930s, Wilson waved a Red flag and warned Tate, “ I am going further and further to the left all the time and have moments of trying to become converted to American Communism” — though he never did convert. Referring to the 1930 manifesto of twelve Southern writers who defended the agrarian society of the South and condemned the increasingly dehumanised society of the North, Underwood observes: “ just as Tate was becoming preoccupied with his aristocratic lineage, Wilson was trying to divest himself of the stigma of his social class. Not long after I ’ ll Take My Stand was published, Wilson announced that there was ‘ no hope for general decency and fair play except from a society where classes are abolished.’ If Tate admired Wilson for criticising the status quo, he nevertheless began signing [his ironic and taunting] letters to him, ‘ With best wishes for a happy Revolution, and with kindest regards to the Comrades—‘I ’ d rather see one than be one. ’”

A major North-South split in American thought, which went back to the Civil War and still provoked hostility among friends seventy years later, signalled the end of their close friendship. Tate complained that Wilson, by moving to the Left, “ has succumbed to all those degradations of values that are tearing society to pieces.” But Tate, while opposing Northern industrialism with Southern agrarianism, personally perpetuated feudal conditions, and exploited both Black and white sharecroppers on his own land.

Wilson ’ s provocative article in the New Republic of July 29, 1931, aimed directly at Tate, blasted “ The Tennessee Agrarians.” He accused them of old-fashioned ancestor worship, “ forever feeding itself on its past,” satirised their pseudo-bohemian life in New York and Europe, and lamented their southward retreat to sentimental and pretentious decay. He also rejected the accusation that the North was to blame for all the social and economic problems in the South: “ after living in dark basements in Greenwich Village, floating with the drift of the Paris caf é s, they have ended by finding these sojourns both expensive and unsatisfactory, and by forming unflattering opinions of the manners and the standards of the intelligentsia. They think tenderly of the South again; and they come, in the end, to blame all the ills of commercialised America on the defeat of the agrarian Confederacy by the money-grubbing merchants of New England.”

The hot issues, then and now, were persistent racism and the cruel treatment of Blacks. As Wilson fiercely wrote of Tate in this article: “ He feels that his tradition of living is somehow humanly right and that the modern industrial society which so flourished when his own was defeated is essentially inhuman and wrong. . . . For the Northerner, the horror of slavery still poisons the memory of that feudal society. . . . The Northerner is sure to be shocked when the Southerner speaks frankly of the Negroes as creatures — an inferior race — for whom political or social equality is utterly and forever unthinkable.”

As the argument heated up in their letters, Wilson revealed that his views were provoked by personal insults as well as by ideology. He angrily complained that in February 1931, visiting his friend during his journalistic investigation of the South, Tate defended his territory, and subjected his Yankee guest to intolerable rudeness and mockery: “ You people certainly take the Southern Cross. Did or did not you and John Ransom and [Donald] Davidson have the abominable manners to sit around and entertain me with prolonged head-shaking and jeering over an unfortunate Northerner who had presumed to come South and try to edit a paper, and with a sour account of other Northerners who had the effrontery to try to hunt foxes in Tennessee? And then you raise the roof when I kid you a little about General Bragg” — the Confederate officer, who lost many battles and frequently retreated.

When Wilson disagreed with Tate and exposed his fatuous beliefs, Tate condescendingly dismissed his arguments instead of answering them. He told Bishop that “ Edmund, sensitive and fine as he is, has always been very innocent philosophically, and now I begin to think he is an irresponsible child turned loose on things he doesn ’ t understand. ” Tate then trained his artillery directly on Wilson and told him: “ Not a single item of your impressionistic picture of an ‘ agrarian ’ is true, and the whole is naturally false. . . . You like to think that we are wistful boys mooning over the past. . . . We draw this moral: you are socially and spiritually bankrupt, and you won ’ t have it that other people aren ’ t — people who still see some hope of building on what they have.” Both writers opposed the capitalism that had caused the Depression, but neither had a viable alternative — Soviet or Southern.

Tate exploded again in an unconvincing diatribe to the West Virginia-born and honorary Southerner Bishop, who was caught in their whirlwind. Tate claimed that Wilson was losing his grip but, once again and with heavy irony, did not refute his attacks:

I ’ ve had some flaming controversy with Edmund. . . . He wrote a piece about our symposium entitled “ Tennessee Agrarians,” the tone of which was superior wisdom before our mere ancestor worship, which is after all, of course, all that we have to offer. I scored Edmund . . . in his falling back on all the prejudices he has ever heard about the South. In general, he accuses us of day-dreaming over the past, i.e., on non-realism. I answer that we are simply calling on the traditional Southern sense of politics, which was eminently realistic, while his [communist] Planned Economy . . . is the most fantastic piece of wish-thinking I ’ ve ever seen. . . I fear something is happening to a good man.

Though the antagonists constantly vented their anger, neither man would ever change his mind.

Tate kept putting the knife into Wilson with a torrent of 1930s letters to Bishop, who probably enjoyed their intellectual combat. Urging Bishop to enter the fray, Tate declared that attacking Wilson would be easy, that his critical assumptions were fundamentally wrong and — with backhanded praise — that Wilson ’ s wide-ranging interests severely limited his writing: “ I do think that E. has great curiosity — indispensable in a real critic. . . . But he goes from one thing to another out of curiosity, and he pauses long enough in between to be credulous. Powers of exposition, but no analytical powers (read again his essay on Val é ry — juvenile, absolutely).” In fact, Wilson ’ s analysis of Val é ry ’ s difficult poetry is quite sophisticated.

Both men were heavy drinkers and got increasingly angry as they got increasingly drunk. It was ironic that in September 1939 Tate got the teaching job that Wilson, an old Princetonian, had also applied for. The English Department at Princeton mistakenly thought that Wilson, but not Tate, was contentious and drank too much. In December the alcoholic Tate sent another shot across Wilson ’ s bow and told Bishop, “ Dr. Wilson has never been quite human, and I am not surprised to hear that he has become a metabolic machine for the transformation of alcohol.” Despite inebriation, Wilson triumphed in June 1938 when Tate and his wife Caroline Gordon stayed overnight with Wilson and Mary McCarthy on Cape Cod. He recited the poetry of Alexander Pushkin in Russian, which Tate could neither understand nor correct.

As both men dug in and hardened their positions, their dispute continued for the next fifteen years. At Tate ’ s fiftieth birthday party in Princeton in 1949, they both had plenty to drink and Wilson exchanged insults with the Southern squire. Wilson regretfully said “ he couldn ’ t stay for another drink; he ’ d already kept his mother ’ s chauffeur waiting too long and must get back to her house in Red Bank.” Deflating Wilson ’ s social pretensions, Tate looked out the door to see who was behind the wheel of the Cadillac and disdainfully remarked with the casual racism of the day, “ That ’ s not a chauffeur, Bunny. Why that ’ s just an ordinary field negra.” During the school and college integration crises in the late 1950s, Tate felt Blacks didn ’ t belong in white universities and imitated a Black student asking, “ Is you done yo ’ Greek? ”

Their conflict about New Criticism recurred when Wilson savaged the stodgy academic journal edited by Tate ’ s revered teacher: “ I would not write anything whatever at the request of the Kenyon Review. The dullness and sterility and pretentiousness of the Kenyon, under the editorship of Ransom, has really been a literary crime.” In January 1951 Tate accused Wilson of indifference not only to his work but also to his life and wife: “ I am perfectly reconciled to your almost total lack of interest in what I write; but it is a little difficult to contemplate a certain coldness, an inattentiveness to what one is, without feeling a little discouraged about it.” Wilson seemed to compound his crime by making negative remarks about Caroline ’ s books. This provoked Tate to exclaim that she would always be polite to him, but Wilson ’ s visit to their home “ would not in the end give her pleasure.”

Wilson, for once, tried to lower the temperature by refuting Tate ’ s charges, and answered Caroline ’ s insulting demurral by inviting himself to visit them — pleasurable or not: “ How on earth can you say that I ’ ve been indifferent to your work? I ’ ve often said both in print and in conversation how highly I thought of your poetry. . . . I have never said anything whatever about refuting your ideas about my criticism in my seminars or anywhere else — in fact, didn ’ t even know you had expressed any ideas about my criticism. . . . I missed Caroline ’ s romping dachshund and your old Confederate flag that used to hang on the wall in the back room. . . . In spite of our unusual loathing of one another ’ s views, I ’ d very much like to see you.”

Tate ’ s unexpected conversion to Catholicism was another personal and extremely contentious issue. As early as 1932, after the accidental death of Wilson ’ s second wife, Tate seemed mildly concerned with his spiritual welfare. He asked Bishop, “ What do you suppose poor Edmund will do now? I wish he might be brought to some notion that would save his soul.” In January 1951, personally affronted by Tate ’ s conversion and doubting his sincerity, the ironclad atheist sent him an insulting letter. Wilson condemned the recent attacks of the Catholic Church on his novel Memoirs of Hecate County, published in 1946 but still banned as obscene in America. He also scorned, with three unusually hesitant “ seems to me,” Tate ’ s willingness to swallow the absurdity of Christian doctrine.

I had already heard with regret about your conversion. . . . My animus against the Catholics lately has been due to their efforts to interfere with free speech and free press. . . . I hope that becoming a Catholic will give you peace of mind: though swallowing the New Testament as a factual and moral truth seems to me an awful price to pay for it. You are wrong, and have always been wrong, in thinking that I am in any sense a Christian. Christianity seems to me the worst imposture of any of the religions I know of. Even aside from the question of faith, the morality of the Gospel seems to me absurd.

Despite Wilson ’ s forceful disclaimers, the keen convert wanted him to enter the fold. Tate insisted that though Wilson played Satan ’ s advocate, he was really a secret Christian and wrote in “ Causerie” (chat): “ None so baptized as Edmund Wilson the unwearied, / That sly parody of the devil.” Wilson fiercely repudiated the imputation that he himself was a believer and mocked Tate ’ s doomed attempt to cultivate the gentle benevolence of his newfound faith: “ He makes against me a malicious, libelous and baseless charge of crypto-Christianity. It is strange to see habitually waspish people like Allen and Evelyn Waugh trying to cultivate the Christian spirit. I hope, though, that conviction will soften Allen, who has lately been excessively venomous about his literary contemporaries. He could never forgive any kind of success.”

Waugh had wittily confessed, “ You have no idea how much nastier I would be if I were not a Catholic. Without supernatural aid I would hardly be a human being.” Tate ’ s zealous Catholicism did not change his sexual behaviour. Religion provided a sanctimonious cover for the old satyr, who went frequently to Mass, confessed and took Communion — and continued to fornicate for the next two decades.

Tate not only attacked Wilson ’ s limitations as a critic, political and social ideas, lack of religious belief and indifference to Tate ’ s person and poetry, but also—though Tate was more secretive and repressed—questioned his inbred puritanism. He believed that the ancestral ghost of Cotton Mather had burrowed into Wilson ’ s conscience like a mole. He frankly told Wilson there was a sense in which, as Matthew Arnold said of the poet Thomas Gray, “ you have never spoken out . There is an area of your sensibility that you have never completely come to terms with.” Wilson, for once, agreed with Tate. In March 1943 he conceded: “ What you say about my writing is more or less true. I feel that I have not really, in general, gotten myself out in my books, and am trying to do so now.” This was ironic since Wilson vividly described his sex life in Hecate County and his journals. By contrast, Tate did not write about his sex life, suppressed all sexual revelations by his would-be biographers and prevented the publication of his love letters.

Wilson and Tate ’ s current reputations are very different. Tate ’ s achievement as poet and critic has been diminished by his unregenerate racism; the second half of his biography was not completed and, except in the South, he is largely forgotten. In old age Wilson had evolved from the priggish young scholar whom e.e. cummings called “ the man in the iron necktie,” into a Churchillian potentate with the fine features of a Roman senator. He published more books after he was dead than most writers publish while still alive: a novel The Higher Jazz, Letters on Literature and Politics, two editions of his correspondence with Nabokov, two collections of essays, and five volumes of his journals from the Twenties to the Sixties . He was celebrated in his centenary year, my biography was published in 1995 and a weak imitation of my book appeared ten years later. In our time Wilson ’ s intellectual brilliance is greatly admired and his reputation is still high.

Jeffrey Meyers, FRSL, has published biographies of Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Wilson in his American Trilogy. His most recent book is Resurrections: Authors, Heroes —and a Spy .

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout the pandemic. So please, make a donation.