Conrad’s ‘Victory’: shades of death

The modern editors of Joseph Conrad’s Victory (1915), J. H. Stape and Alexandre Fachard (Cambridge UP, 2016), begin with an absurd statement about Conrad: “After 1895 the history of his life is essentially the history of his works” — as if his life apart from his writing had no meaning. But they immediately add a six-page chronology of his life and include 70 pages on his composition of the novel. Still, this massive edition has a valuable introduction by Richard Niland and excellent explanatory notes.

Victory has a Far Eastern setting, complex narrative, effective literary allusions and vital themes. Niland notes the “philosophical scepticism and melodramatic intensity, the originality, inventiveness” and subtle transformation of literary sources. Conrad described the book with deliberate modesty and vagueness, “It’s in the East. There’s a man and a girl in it with some rascals and other people round them.”

The editors write that the German Schomberg, one of the rascals, “particularly dislikes persons who do not frequent his establishment,” but the hero Axel Heyst does stay at his hotel, where he ignites the tragic events. Schomberg’s vindictive hatred of Heyst is provoked by thwarted passion, wounded vanity and the humiliation of being defeated in love by a man he considers less virile than himself. Schomberg seemed especially hateful in 1915, when Britain was fighting a war against Germany.

Niland quotes my 1986 article (and photograph) that revealed that the ladies orchestra, including Lena, was inspired by the “ ‘Orchestra of Virgins,’ an outfit of society ladies that the Ranee of Sarawak had got up to facilitate courtship and marriage.” Conrad explained that “the Victory of the title is related directly to Lena’s feeling of Victory—the triumphant state of mind in which she dies” while sacrificing her life for love.

The usually perceptive critic Albert Guerard foolishly called the “badly written” Victory “one of the worst novels for which high claims have ever been made.” Thomas Moser, whose Harvard dissertation was directed by Guerard, dutifully followed his master in his book on Conrad’s “decline”. But Victory marked a high point in Conrad’s achievement, not his decline, and he published his great story “The Shadow-Line” in 1917. Graham Greene, whose novel A Burnt-Out Case (1960) was inspired by Victory, called it one of “the great English novels of the last 50 years.”

The most useful explanatory note describes the European control of the Malay Archipelago: “During Conrad’s time in the region, the area was politically parceled out to the Netherlands as the Dutch East Indies; to Britain in Malaya (comprising present-day Malaysia and Singapore) as well as territory on Borneo [Sarawak and North Borneo], two-thirds of which island was under Dutch control; Spain, which held the Philippines; Portugal, which held Timor; and to Germany, which declared a protectorate in northern New Guinea.”

More could be said about the explanatory notes and comments on Victory. The editors have missed several of Conrad’s important literary allusions:

30- “made his great renunciation”—Dante, Inferno, 3.60: “che fece il gran rifiuto.”

72- “without colour, without glances, without voice, without movement”—As You Like It, 2.7.139: “Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

98- “screwing his courage up to the sticking point”—Macbeth, 1.7.58: “Screw your courage to the sticking-place.”

274- the evil “gentleman seems devoted to mystification”—King Lear, 3.4.147: “The prince of darkness is a gentleman.”

347- “in the very shades of death”— Milton, Paradise Lost, 2.621: “rocks, caves, lakes, fens, bogs, dens, and shades of death.”

350- “Nothing”—King Lear, 1.1.99: “Nothing will come of nothing”; and Siegfried’s magic sword Notung in Wagner’s Ring.

Conrad compares Heyst to the Swedish warrior-king Charles XII. After a series of military triumphs, the king came to an ignominious end. In 1718, during an insignificant conflict in a remote region of Norway, he was shot in the head by an unknown Danish soldier and died at the age of 36—the same age as Heyst in the novel. (Heyst had 18 years in school and 3 years with his father before spending 15 years in the East Indies.) The editors don’t mention that in “The Vanity of Human Wishes” (1749)—a good title for the book by Heyst’s father on “the vanities of this earth” —Samuel Johnson wrote of Charles XII:

His Fall was destin’d to a barren Strand,

A petty Fortress, and a dubious Hand.

He left the Name, at which the World grew pale,

To point a Moral, and adorn a Tale.

The basic plot of Victory comes from Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Ebb-Tide (1894): three evil men in pursuit of treasure invade the remote island of a decent man who must confront them. But Conrad brilliantly transformed Stevenson’s melodrama into a superb novel.

The meaning of Victory is deepened and enhanced by historical, economic, military and political themes. The novel has fascinating autobiographical revelations about Conrad’s father and wife, and important allusions to coal mining and nationalistic hatreds. Victory has subtly recurrent patterns, intriguing characters and daring sexual imagery; the poignant Liebestod in the conclusion is highly allusive, psychologically complex and deeply moving.

Conrad doesn’t explain why Heyst’s Tropical Belt Coal Company has lost capital and gone bust. In fact, coal was costly to mine, transport and use. Once mined, it had to be sent to the coaling stations that had no local mines. The ships using coal needed a convenient chain of friendly ports, required a lot of time to refuel and became sitting targets in wartime. Once the coal was loaded onto a ship, it had to be continuously shifted from the hold to the boilers. In Trafalgar: The Nelson Touch, David Howarth observes that the admiral’s tremendous victory against the French and Spanish in 1805 marked the history of fuel throughout the nineteenth century: “The victory under sail that afternoon established a supremacy at sea that lasted all through the age of steam and into the age of oil.” Andrew Roberts explains why in 1912, when Winston Churchill was First Lord of the Admiralty, the British Navy changed their battleships’ fuel from coal to oil: “This made the vessels lighter and consequently faster. Ships no longer had to sail from coaling-station to coaling-station and could now stay at sea for much longer.”

Heyst’s name suggests the heist of Lena, and that he’s the highest of all the corrupt characters. Like the tragic Shakespearean heroes defined by A. C. Bradley, Heyst “contributed to the disaster in which he perishes”. The diabolical Gentleman Jones recognizes the homosexual element in Heyst that has led to his fear of women, his guilt and his impotence with Lena. Jones enjoys implicating his victim in his own corruption and stresses the similarities between himself and his secret sharer: “Something has driven you out [of society]—the originality of your ideas, perhaps. Or your tastes.” Conrad effectively uses Heyst’s repressed homosexuality to explain his emotional sterility and denial of life. His homosexuality symbolises the conflict between his desire for isolation and his need for love.

The structure of Victory, in which all the characters are deceived, is brilliant. Schomberg, the orchestra leader Zangiacomo, Heyst and Ricardo all want to possess Lena. Heyst, Lena and Mrs. Schomberg deceive Schomberg so tharLena can escape to Samburan with Heyst. Schomberg deceives the two criminals, Jones and Ricardo, about Heyst’s nonexistent treasure. Ricardo and Heyst deceive Jones about Lena’s existence on the island. Lena deceives Ricardo to protect Heyst. Heyst’s servant Wang deceives him by stealing his revolver. Heyst and Lena mistakenly fear they have deceived each other.

Lena, named after Magdalena, the reformed prostitute in the New Testament, is experienced in fighting off predatory men such as Schomberg and Ricardo. Her sexual experience contrasts with Heyst’s sexual repression. Though she’s been a prostitute, she still seems virginal and innocent. Lena’s father has taught her to play the violin and Heyst, who rescued her, is her older father figure. When Lena is alone with Heyst on the island of Samburan, she doesn’t practice the violin, the symbol of her miserable life, to pass the time, nor play music to amuse the cultured Heyst.

In the past Heyst saved Morrison’s ship in Timor, and he now saves Lena, who’s enslaved in Zangiacomo’s orchestra. Both rescues end badly. Schomberg falsely accuses Heyst of murdering Morrison for his money and sends the criminals to steal his treasure.

In the tragic climax of Victory the jealous Jones fires at Ricardo and kills Lena, who dies in Heyst’s arms. Jones then kills Ricardo and drowns. Wang kills Pedro. Heyst sets his house on fire and dies in the purifying flames. But Lena (also called Alma) redeems Heyst’s soul, his belief in humanity and his capacity for love. The intensely visualised death of Lena is modeled on the historical paintings of the death of Admiral Nelson at Trafalgar in 1805 by A. W. Davis (1806) and by Benjamin West (1808), which Conrad saw in the Greenwich Maritime Museum.

The editors of this volume do not notice Conrad’s strong suggestion that the invasion of Heyst’s island symbolises the disastrous partition of Poland by three countries in the late 18th century. The stiff and formal Jones is Prussia, the rabid and reckless Ricardo is Austria, the primitive and barbaric Pedro is Russia.

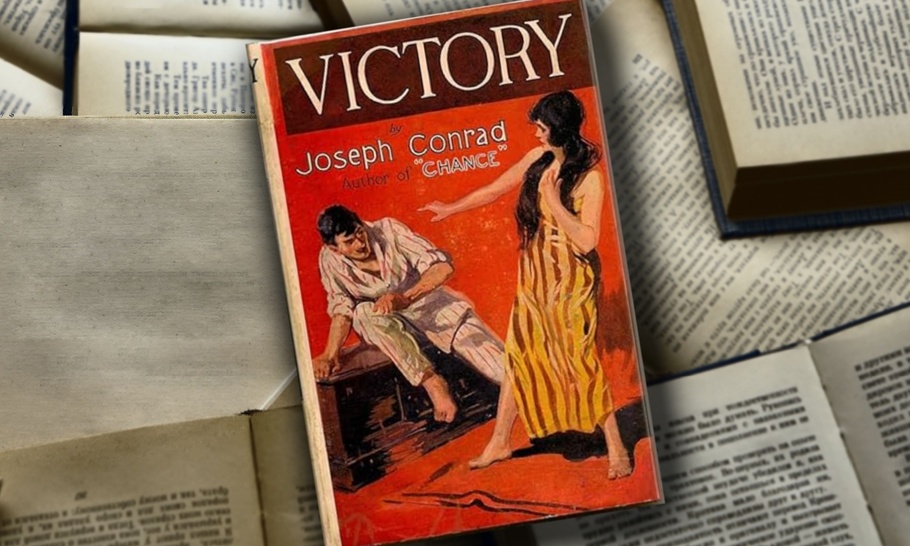

The English edition of Victory had a provocative dust jacket, not reproduced in this edition. Lena, standing up with bare feet and with long dark hair streaming onto the breast of her striped sarong, extends her bare arm to hold off the dark-haired moustachioed Ricardo, clad in striped pyjamas, cowering beneath her during his attempted assault.

Victory became a play by Macdonald Hastings in 1919 and an opera by Richard Rodney Bennett in 1970. The latest of 12 film versions, with superb acting, appeared in 1996. Willem Dafoe plays the increasingly emotional Heyst, the French actress Irene Jacob is the frail and vulnerable Lena, Sam Neill is the malefic Jones and Rufus Sewell the menacing, feral Ricardo. Shot in Indonesia and faithful to the novel, the film was expertly written and directed by Mark Peploe. Augustus John’s portrait of the elderly Thomas Hardy (1923) was used to represent the “portrait of Heyst’s father, signed by a famous painter.”

Jeffrey Meyers has published Joseph Conrad: A Biography (1991) and four introductions to his works. His 43 Ways of Looking at Hemingway will appear with LSU Press in November.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.