From the deathbed of classical chess

Marcel Duchamp and cubist chess (image created in Shutterstock)

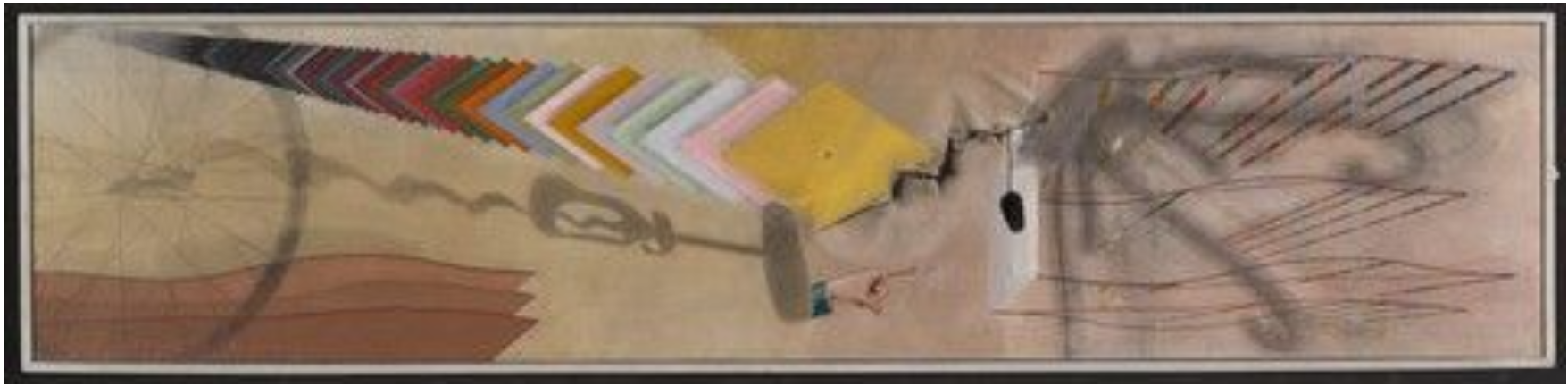

Marcel Duchamp, the quintessential chess playing artist, concluded his conventional artistic career with a work enigmatically entitled Tu m’ which has widely been interpreted as either the start of the sarcastic phrase tu m’ennuies (“you bore me”); or tu m’emmerdes (“you annoy me”). Duchamp was apparently so bored with representational art that he could not even drag himself to finish writing out the full phrase.

Tu m’ by Marcel Duchamp, 1918, Yale University Art Gallery (Gift of the Estate of Katherine S. Dreier)

What fascinated Duchamp, as indeed it fascinated his contemporary, the great chess theorist Aron Nimzowitsch, was the cerebral process behind the work, not the mere physical manifestation. It was possible to perceive this process in motion already with Duchamp’s Large Glass, where his array of so called Moules Maliques are the most strikingly metaphorical depiction of chess pieces in the history of modern art. It is a homage to our game on the same complimentary level as Goethe’s verbal pronouncement that chess is “the touchstone of the intellect”, der Probierstein des Gehirns. In the same way that Duchamp had become bored with conventional art, Magnus Carlsen (who voluntarily renounced his world championship title last year) has patently lapsed into Ennui or boredom with classical chess.

To begin with, it is vitally important to grasp the difference between classical chess, one game per day, conducted at slow time limits, and rapid play or blitz, with multiple games per diem and minutes, rather than hours for each game. In the past the great champions — Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Botvinnik, Kasparov et al — their world titles solely and exclusively through the classical medium. In contrast, Magnus Carlsen, the undoubted major force in contemporary chess, now despises and rejects the classical format, in favour of the quick play alternatives. For the latest developments I now paraphrase official pronouncements from the powers that be in global chess officialdom. FIDÉ is, of course, the acronym for the Federation Internationale des Échecs, the world governing body for our mental sport.

Despite qualifying for the Candidates Tournament 2024 by winning the 2023 FIDE World Cup in Baku, Azerbaijan, world #1 Magnus Carlsen has officially withdrawn from the event. Carlsen had previously stated his disinclination to compete after reaching the semifinals of the World Cup and in some private interviews; however, the formal Letter of recusal was received by FIDÉ on January 13, 2024.

According to the FIDÉ Candidates qualification regulations, the vacant slot at the FIDÉ Candidates Tournament 2024 goes to the next highest finisher in the 2023 FIDÉ World Cup, Nijat Abasov (Elo rated 2641, from Azerbaijan), who was fourth in the tournament final standings.

The current lineup of the FIDÉ Candidates Tournament 2024 is, therefore, the following:

– Ian Nepomniachtchi, representing FIDÉ (formerly a Russian) 2023 Championship finalist;

– Praggnanandhaa R, India, 2023 World Cup (2nd);

– Fabiano Caruana, USA, 2023 World Cup (3rd);

– Nijat Abasov, Azerbaijan, 2023 World Cup (4th);

– Vidit Santosh Gujrathi, India, 2023 Grand Swiss (1st);

– Hikaru Nakamura, USA, 2023 Grand Swiss (2nd);

– Alireza Firouzja, France, Best by Rating ;

– Gukesh D, India, 2023 FIDÉ Circuit Winner.

The FIDÉ Candidates Tournament 2024 will take place in April 2024 in Toronto, Canada. The winner of this 8-player double round-robin (all-play-all twice) will become the Challenger for the chess crown and play in the FIDÉ World Championship Match against the reigning world champion Ding Liren (China).

Meanwhile, former classical world champion Magnus Carlsen has won the FIDÉ World Cup for the first time in his career, whilst also retaining his FIDÉ World Rapid and Blitz crowns, winning his 5th World Rapid and 7th World Blitz titles. According to my count this means that, including classical time limit championships, Carlsen has now garnered no fewer than seventeen world titles. Previously Botvinnik with five (all classical) and Kasparov with seven (six classical plus the world junior championship) held the record. But in the past, it could take months to win a world title, while the clearly impatient Carlsen can now pick up a couple of quick play laurels in less than one week.

Surely some sort of titular inflation is involved here, a devaluation of world championships. Yet the acceleration of these accolade-bearing events confers two advantages. First of all, speeding up of time limits has made chess, which is now widely followed online in real time, furnished with expert commentary, exponentially more popular and accessible. The online chess service Chess.com has become the world’s largest chess site, with a community of more than 150 million members from around the world playing more than 10 million games every day. Chess.com organizes and broadcasts the world’s biggest chess events featuring multi-million-dollar prize funds captivating millions of viewers. Chess.com is the 114th ranked site on the internet. In June 2023, Chess.com was named one of TIME’s 100 Most Influential Companies. The natural concomitant to this development is that strong players are being discovered and offered opportunities at increasingly younger ages. Prodigies now proliferate and if an aspiring player is not of Grandmaster strength by age twelve, one might as well concede and give up the quest. In the interests of balanced reporting, I should remind readers that should they wish to play chess without the commercial basis of most Chess.com services, the Lichess.org platform remains free to all.

The second advantage is that blitz victories, which I had previously dismissed as unimportant, have now been crowned with a nimbus of legitimacy. Nevertheless, I still cannot help but feel a twinge of nostalgic remorse, that the old classical battles between the world’s best gladiatorial chess minds, are now a thing of the past. By recusing himself from classical chess, while winning every other title in sight, I cannot help but feel that Carlsen has confirmed those elegiac words of Oscar Wilde:

Yet each man kills the thing he loves,

By each let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

Has Carlsen has dealt the death blow with a brutally brief letter? The contemporary legitimisation of such quick games makes me wonder if Carlsen is right. Is it possible to overthink our game? Hence is chess, in fact, evolutionarily designed to be played quickly? Beauty is a by product of the quest for victory, and the aesthetic element may emerge equally and serendipitously in fast chess as well as in the classical variety.

However, there is sometimes the downside in the nature of the win, where blunders can prove the conclusive feature, rather than successfully viewing beyond the opponent’s deepest horizon? Two Spanish examples follow:-

In Blitz contests, Carlsen vs. Grigoriants

But also, in Rapidplay, Carlsen vs. Gareyev

Lest I not demonstrate my own pre-disposition, some of my own blitz games follow…

and we can look at another in some detail:

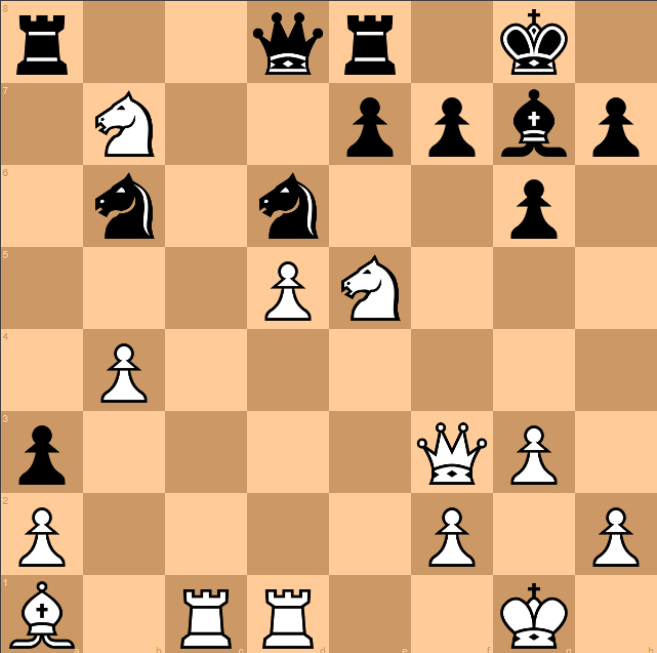

Raymond Keene vs. William Hartston

Cambridge University blitz tourney, 1968

Notes by Raymond Keene

1.d4 Nf6 2. c4 g6 3. Nf3 Bg7 4. g3 O-O 5. Bg2 d5

A fluid counter-attacking line, which aims to set up White’s pawns as a target for Black’s minor pieces, a common theme of all Grünfeld systems.

6.cxd5 Nxd5 7. O-O Nb6

Alternatively, 7… Nc6 8. Nc3 Bf5 9. Nd2 Nxc3 10. bxc3 e5 11. d5 Ne7 12. e4 when White dominates the centre and Black must lose time with his attacked bishop, Keene-Miles, London 1973. Also premature is the attempt at central clearance 7… c5 8. dxc5 Na6 9. Ng5 Ndb4 10. Nc3 Nxc5 11. Be3 Nca6 12. Qb3 h6 13. a3 Nc6 14. Rfd1 with a clear advantage to White, Keene-Barreras, Capablanca Memorial 1974.

8.Nc3 Nc6 9. e3 Be6

Preparing a manoeuvre to challenge White’s raking bishop on g2. The slower 9… h6 10. Ne1 Nb4 11. a3 N4d5 12. Nxd5 Nxd5 13. Nd3 also left White in command of the central zone in Keene-Williams, Cambridge University Championship 1970. Perhaps best, though, is direct action with 9… e5 10. d5 Ne7 11. e4 Bg4 when 12. a4 c6 13. a5 leads to complications, Keene-Hollis, Marlow Masters 1970. Rowson’s book on the Grunfeld urges the merits of 9… Re8.

10.b3 Qc8 11. Re1 a5 12. Bb2 Re8

This move, slightly weakening the f7 square, has fateful consequences, which, however, at the time were impossible to foresee. If instead 12… a4 13. Nxa4 Nxa4 14. bxa4 and although White’s extra pawn is enfeebled, it is not clear how Black can regain it.

13.Ne4 Bh3

The exchange of bishops removes a valuable white piece, but loses time and gives White the chance to establish a grip over the queenside terrain.

14.Bxh3 Qxh3 15. Nc5 Rab8 16. Rc1

Reviving the threat of Nxb7, a tactical motif which will recur.

16… Qc8 17. Qd2 a4 18. b4 Na7

Over the next two moves, White improves his chances further by invading the centre.

19.Ne5 c6

Playing to establish a light-square blockade.

20.e4 Nb5

White could now cement the queenside with 21. a3, but judged that if Black himself were to advance his pawn to a3, it would tend to create a source of weakness, rather than strength.

21.Red1 Nd6 22. Qe2 Qd8 23. d5 a3

Hoping to unbalance the defence of White’s aggressively-posted knight on e5, but White’s coming retreat is a complete answer.

24.Ba1 cxd5 25. exd5 Rc8

Here, White now has available the crushing 26. Nxf7!!

26. Qf3 Ra8

White’s 26th set up an obvious attack against the weakling on a3, also a masked threat against Black’s king’s defences. The only chance would have been 26… Bxe5 but the surrender of Black’s fianchettoed bishop would invite all sorts of future problems in his king’s field.

27.Nxb7!

A decisive deflecting sacrifice.

27… Nxb7

Black had no choice, but now White’s legions storm in.

28.Qxf7+ Kh8 29. Nxg6+ Black resigns 1-0

Ray’s 206th book, “Chess in the Year of the King”, written in collaboration with former Reuters chess correspondent, Adam Black, appeared last year. Now his 207th, “Napoleon and Goethe: The Touchstone of Genius”, has also appeared. Both books are available from Amazon and Blackwells.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.