The story of Alaska

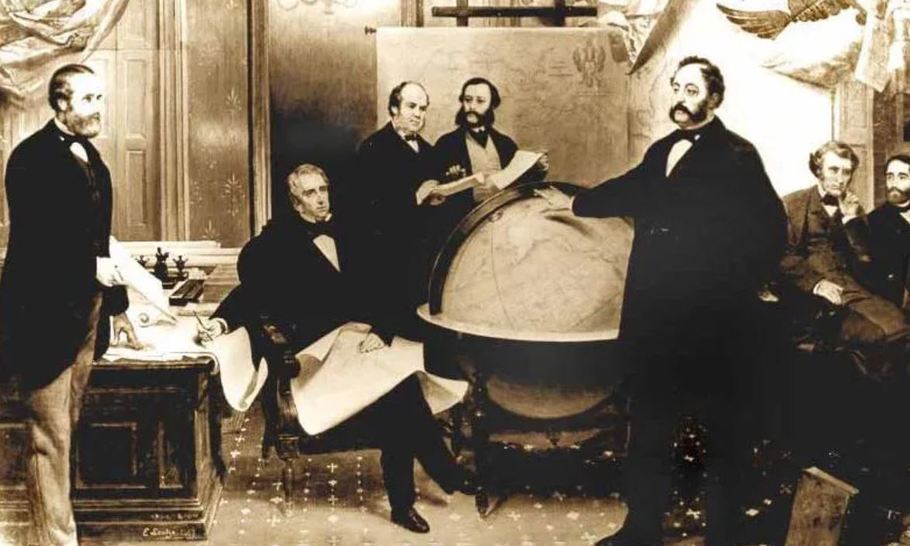

The signing of the Alaska Treaty of Cessation on March 30, 1867.

Alaska is not very often a place of political interest, but following the Trump-Putin summit, it is now. If any journalist believes that he or she has been an expert on Alaska for long, I must put in a claim for priority. By the age of nine or ten, well over 80 years ago, I knew as much about Alaska as almost anyone in Europe. Where did all the wisdom come from? From the children’s library in Budapest. They had seventy volumes of Jules Verne. I read each one, but the best thumbed of them all was the eponymous César Cascabel.

César Cascabel was the head of a troop of circus artists. They were performing in California when they decided they had had enough of the United States and they wanted to return to France, their native country. The problem was that their savings were stolen, and they could not afford the ship fare to France. So they had to make a drastic decision. They decided to return to France via the Bering Strait, through Siberia and Central Russia, with their horse-drawn carriage, the Belle-Roulotte. This was in the 1860s when the United States started negotiations to buy Alaska from Russia. As in all such journeys, one adventure follows fast on the heels of the one before, including close encounters with native Alaskans, helping a political fugitive from Russia, being stranded on an iceberg and – critically — witnessing the transfer of Alaska from Russia to the United States while passing through Sitka in 1867.

How did it become Russian in the first place? Russia began expanding eastwards in the mid-16th century and reached the Pacific Coast in the mid-17th. Peter The Great commanded Vitus Bering to look for potential colonisation opportunities in the North Pacific. One objective was to establish access to the fur trade on Alaska’s coast, as Siberia was not providing enough to meet demand by that time. Bering obliged and, through his second attempt, discovered the North American mainland and claimed Alaska for the Russian Empire. In 1799 Russia issued a decree claiming the North American territory north of the 55th parallel.

Presumably, the Russians wanted to do business. They even founded a company, called the Russian-American company, but the Russians were not good colonisers. Baranov the local governor was able to look after Russian Alaska when sober, but he liked the company of his drinking friends a little too much. Ebbets, a fur trader from Boston, wrote in the early 1800s: “They all drink an astonishing quantity. Governor Baranov not excepted. I assure you it is not a small tax on the health of a person trying to do business with him.“

Rezanov, the nobleman and statesman in charge of the Russian-American Company, arrived at Sitka in February 1806, finding the colonists suffering from scurvy and starvation. He acquired a ship, the Juno, and embarked on a trade mission to California to obtain food supplies from the Spanish (who then ruled the region) in exchange for Russian goods. Rezanov’s ship arrived in San Francisco in March 1806. The Russians and the Spaniards got on very well because they had different aims. They were not competitors. The Russians were interested in the fur trade, the Spaniards in the greater glory of their most Catholic King.

During his six-week stay in San Francisco, not only did Rezanov succeed in bartering food but he embarked on a love affair with the beautiful and sophisticated 15-year-old daughter of the Spanish Governor of Alta California, María de la Concepción Marcela Argüello y Moraga, or, briefly, Conchita. Rezanov made a huge sacrifice for his country, promising to marry Conchita despite their different religions. He set things in motion to obtain the triple permissions needed: from the Pope, the King of Spain and the Russian Emperor.

Unfortunately the story did not end well. Rezanov went back to Sitka in May 1806, with his food supplies, then back to Russia and died of exhaustion and fever in Krasny Yar in 1807, never returning to his beloved Conchita. According to a popular Russian Rock Opera, Juno and Avos, their love was genuine. Conchita waited for Rezanov’s return, not believing reports of his death, for decades. When she was finally convinced that he was no more, she became a nun, taking a vow of silence until her death.

Meanwhile there were lots of changes in Russia. When the long ruling Czarina Catherine II (“the Great”) died in 1796, she was followed by her son, who became czar under the name of Paul I. Paul heartily disliked his mother. Whatever mummy did, Paul wanted the opposite. No doubt due to inbreeding, Paul was a little dim-witted, his only interests were playing with toy soldiers and suppressing Polish attempts at independence of Russia. He did not have much interest in the Russian territories in America. Neither did his successors: Alexander I, Nicholas I and Alexander II.

By the 1860s the only people who regularly crossed the Bering Strait were fur traders and colonial administrators. Trading in Alaska never became profitable. Alexander II had just lost the Crimean war, which burned a large hole in the treasury. The way to replenish his finances was to sell Russian real estate. He made an offer to the US they could not refuse: a bargain price of 7.2 million dollars for all the Russian colonies in West America (as I am sure, Vladimir Putin pointed out to Donald Trump when musing about history, as he likes to do).

Now returning to the adventures of Cascabel, who did manage to return to France, the book is written beautifully within the series Extraordinary Voyages. I must point out that not only did reading Jules Verne made me an expert about the transit from Alaska to mainland Russia, but I developed other expertise as well. Jules Verne made the impossible plausible. I learned about space travel, how to get to the moon, about journeys under the seas, round the world and to the centre of the Earth.

International politics was also part of Jules Verne’s interest. As a Hungarian, I was pleased to find out that Hungarian patriots did attempt to overthrow Habsburg rule of Hungary. This was a great novel titled Sándor Mátyás (Mathias Sandorf), but that’s another story.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.