Naïve painting: Ivan Generalic and his school

Milan Nadj’s Skaters in a Winter Landscape (1989)

I

Ivan Generalic (1914-92), the son of poor Croatian peasants, finished only five years of primary school. Like the young Giotto making a perfect circle, he drew constantly as a child, sometimes on paper that was used to wrap food in the village shop. Throughout his life he continued to milk his cows, feed his pigs, cultivate his land, pick his plums, and go hunting and fishing. For four years Generalic worked as a drawing teacher at the elementary school in Hlebine, his native village. He married a local girl in 1934, had a son and did his compulsory military service in 1936. Recalling his painting Under Arrest (1934), he said, “I was arrested too, before the war, because I painted the injustices the peasants had to put up with. The police came often in those days, and since no one was ready to give up his animals or his last sack of grain, many were beaten up or even arrested.”

In The Magic World of Ivan Generalic by Nebojsa Tomasevic, the artist explained, “I still live in the village. I paint when I have time, when there is not work in the fields—in the winter, on rainy days, and on Sundays.” Mentioning that icons were traditionally painted on glass, he added, “I first draw a picture in pencil on paper; then I cover it with a piece of glass the same size as the drawing and then paint on the glass. . . . I changed to glass when I realized that with this technique I could obtain fresher colours and put in more details. Painting on glass means working on one side and then observing the result on the other.” His wife gave him a dubious compliment, “You are not only naive, but also childish.”

He vividly portrays snow, trees and dark woods, peasants, work and animals: cows, pigs, cocks and stags; music, weddings, festivals and funerals; the dangers of fire and flood. He uses vibrant colors, contrasts light and dark, has sharp outlines, creates larger than life figures who dominate the foreground and places the village in the background. In his magical realist Fish in the Air an angler hooks a huge hooked fish from the water, out of scale and much larger than himself, that leaps high up in the sky. His paintings show his closeness to farm animals, the life of toil, the local fear of natural disasters and sudden death. Pagan beliefs have survived in this Catholic country; and the rooster, crucified in his painting The Scarecrow, is considered a guardian of the home whose cry warns of invaders. In his Deer in the Wood, as in classic paintings of St. Eustace, one expects a crucifix to appear between the antlers of a white stag that lives in a deep forest of gleaming white trees.

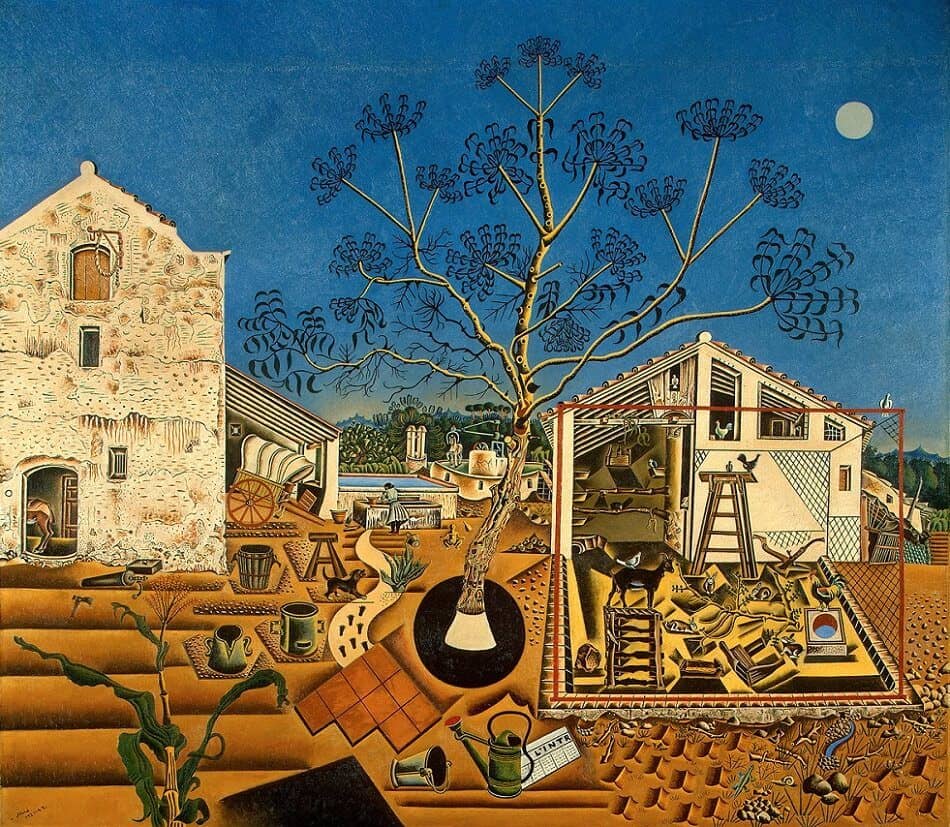

My Studio wittily alludes to Impressionist plein air painters and the rural details in Joan Miró’s The Farm (1922). Generalic portrays himself holding a palette and standing in front of his easel and next to his wooden box of paints. He wears a black shirt and white cap, white jacket, white pants patched at the knees and laced tan boots. He’s surrounded by a crowing rooster, a huge red cow with a blanket on its back, four ducks floating, and one black pig sinking, in a shallow pond in front of the artist.

The Farm, 1922 by Joan Miro

In Woodcutters three white-clad, red-capped, axe-wielding men have climbed up the tall brown trees, wedged themselves in the crotches and, using the same synchronised raised-arm gesture, cut the bare branches that fall to the ground. Two women below them gather the wood and heave it into an ox-drawn cart. Wide-winged, long-tailed seabirds flutter beneath the trees. In the right foreground a strangely misplaced ostentatious peacock displays the pink eyes on its long blue tail feathers.

Morning Work in the Winter portrays the ever-busy peasants in the cold season. In front of barren trees, next to the frozen river and snow-covered wooden houses dripping with icicles, six farmers and a child chop wood, fork hay, draw water, and feed the cow, pigs and a hungry chained brown dog that guards the house.

Cat in Candle-Light recalls Balthus’ pictures of cats. In the background a dark night sky is faintly lit by a quarter-moon reflected in a nearby cloud. A huge black cat with pointed ears, yellow eyes split by a black vertical line, pink nose and jutting whiskers sits next to a tall candlestick with a red-flamed blue candle burnt low. Generalic described the cat’s eyes as “little incandescent lamps shining in the darkness of the night.”

The pathetic Plucked Cock, which echoes Chaim Soutine’s Dead Fowl (1924), lies across a blue oval dish that’s too small to hold it, faces away from the open window and has a sharp knife pointed at its head. The artist humanises the naked, executed, corpse-colored fowl by giving it a drooping head, inflated gullet that looks like a woman’s breast and sadly folded wing like a protective arm.

Killing the Pig takes place in the tiny, snow-covered village spiked by barren trees. The huge black pig lies on its back, feet stiff in the air, in a bed of flames. The farmer, wearing a leather apron, feeds the fire with dry hay. A small piglet watches its roasting mother, which foreshadows its own future fate: today’s pig is tomorrow’s bacon. Generalic writes, “In the period before Christmas every family slaughters one or two pigs to make lard and prepare salted meat for the whole year. To singe the pig’s bristles after you’ve killed it, you put it on the ground covered with a layer of straw, and this you set on fire.” The Yugoslav poet Vasko Popa describes the necessary cruelty from the sow’s point of view: “Only when she felt / The savage knife in her throat / Did the red veil / Explain the game / And she was sorry / She had torn herself / From the mud’s embrace / And had hurried that evening / From the field so joyfully / Hurried to the yellow gate.”

In Village in Flames the fire explodes and scratches the dark night sky. Tongues of flame sear the thatched roof of a house and show through the windows as men rush up ladders with buckets of water. In the left foreground a woman in a blue shawl holds a candle and prays for help. In the right foreground a woman seated next to a shining oil lamp wears a red skirt that matches the fire. Beneath the ladders frantic villagers, one woman throwing up her hands in hopeless despair, try to supply the water. But the house is doomed to ashes.

The Circus and The Beggar portray the village’s hostility to suspicious outsiders and grotesque foreigners. The Circus, a picture about preparing to entertain the remote village, is bizarre. Three white mushrooms grow incongruously at the roadside. A bare-breasted woman with tied white cap, stringy grey hair and thick nose, looks backward while dragging a small cart that’s usually pulled by a horse or donkey. The cart carries a blue bag with her possessions, an alert owl, a curious monkey peering out of a cloth window and a gigantic brown rat—but no traditional dancing bear. This strange menagerie will soon perform for the peasants.

The Beggar, on his way to seek alms, staggers along under a crescent moon, with huge splayed toes and rough-cut green crutches. He has wildly floating grey hair, mustache and whiskers, a tilted wrinkled face with wide eyes and broad nose. He wears a red cloak with ragged sleeves trimmed with white, and carries a blue bag hanging from his neck that holds his worldly goods. He passes a small closed church with a brown steeple as his unnaturally yellow, sharp-clawed mongrel points the way to nowhere.

Portrait of an Old Man depicts the painter’s father-in-law. Seen close up looking to the left, he fills the frame. He has thick eyebrows, dark eyes with pouches underneath, deep-grooved dusky face, strong jutting nose and moustache that curves beyond his mouth. His powerful right hand holds a long-stemmed pipe with a red bowl and metal lid. The tendons stick out of his neck, and he wears a buttoned-up white shirt and thick brown jacket with the painter’s name and date on his front pocket. Generalic wrote, “I prefer painting old people because in old faces I can see better the difficulties of life, poverty and suffering.”

The strange and spooky The Death of Mirko Virius imagines the death of Generalic’s close painter-friend, killed in a concentration camp in 1943. He lies full length above ground instead of beneath it, as if the artist is unwilling to part with him. Barefoot, he’s dressed in a long black cloak, has a white cloth across his forehead, and clasps his hands. Surrounded by thirteen candles, he’s watched by four ex-prisoners who mourn him, standing at a respectful distance in a green field and near an isolated four-story, red-roofed house. In the background the Drava River, bordered by willows, glides gently past an island with a tiny house and disappears into the distant left background. Generalic said, “Mirko’s rooster is there as a friend of man; it has flown up to him and bends toward his body as though it wanted to whisper something to him.”

Generalic belongs to the naïve tradition that includes Edward Hicks’ Peaceable Kingdom, Henri Rousseau’s jungle landscapes, Grandma Moses’ tidy towns and Marc Chagall’s magical villages. Though wholly individual, Generalic’s paintings also resemble those of other well-known artists. When he exhibited his work in Paris in 1953 he saw Pieter Brueghel’s works in the Louvre. Generalic’s Dancing in the Farmyard is similar to Brueghel’s Kermesse (1528); his Stacking the Hay and sleeping peasants in Women at the Water recall Brueghel’s Harvesters (1565); his Gypsy Wagon echoes Brueghel’s Hunters in the Snow (1565). At the Table suggests Van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters (1885).

Generalic affirmed that with Gypsy Wedding, “I wanted to show that even poor people can be happy, even if they don’t live in fine houses with tables loaded with all God’s gifts. You can celebrate in the snow, in the woods, in mud huts, or next to a bonfire under the open sky. I hope I’ve succeeded in showing that even those who live in poverty are able to have their share of happiness.”

II

Some years ago a Croatian friend told me about a group of naïve painters, artistic disciples of Generalic, who lived in the same remote village 70 miles northeast of Zagreb, on the eastern border with Hungary. I had to use a large scale map in the Geography Department of the university to find the tiny Croatian hamlet of Hlebine. In July 1990 my wife and I drove south from Salzburg to Zagreb and Koprivnica to find his native habitat. Since there were no signs pointing to the deserted region in the east, we asked directions in French.

We finally reached Hlebine—on the Drava River, a tributary of the Danube— which at the time had an ever-decreasing population of 1,600. It boasted dirt streets, slow-moving oxcarts, thatched roofs, and women in aprons and head scarves. Such villages, still existing in remote parts of Eastern Europe, were satirised in the film Borat and dramatised in the Czech film Zelary (2003).

The painters wanted to keep the village traditional and frozen in time so they could paint it in the old way. Seeing it was like going back to traditional peasant life in a pre-industrial age. The village had its own dialect and no one spoke any foreign tongue. When we mentioned an artist’s name, a man got into our car and pointed the way to his house. Our guide had a flat cap, gold teeth and German perforated summer shoes.

The artists we met were born in Croatia, Martin Kopricanec in 1943, Milan Nadj in 1945. During those tragic years in World War Two, Yugoslavia was torn apart by the civil war between Communists and Croatian Fascists that took place at the same time the Communists fought the Nazis who had occupied their country. Both artists, whom we saw separately, had arched noses and thick black hair combed straight back over their wide Slavic foreheads. They spoke some German, were pleased that we had come from far away to seek them out and offered us cups of thick Turkish coffee. Their houses were also their galleries. We were able to choose our heart’s desire from a dozen recent pictures, and paid for them with Deutschmarks. Joined by the artists and an ever-increasing group of congenial men, we celebrated our acquisitions at an outdoor inn and had a rough but hearty feast of grilled cevapcici sausage. I had to fend off the endless toasts to eternal friendship with fiery slivovitz and rough red wine, so I’d be sober enough that day to escape from Yugoslavia.

In the preface to Kopricanec’s catalogue, he closely followed the principles of his Master Generalic: attachment to his native village, love of the natural world, aesthetic response to the seasons, nostalgic reveries and joie de vivre: “My painting is my great love, with memories of childhood days, beauty of my landscape, birdsong in the spring, colorful autumn forests and white roofs of the peasants’ houses in winter. That is my life and hard work in the homeland I would never leave. Those are the dreams and fantasies in my paintings. All that inspired my joy in life, so I might share it with people in the whole world.” (My translation from German.)

After some deliberation we chose Kopricanec’s Winter Landscape (1990), painted with oil on glass, measuring 13×11 inches. In the left foreground an outsized rooster faces left, with a jagged red comb and wattles, bright eye, green neck, speckled tan chest and flowing colored tail feathers. Standing with firm spurred legs in a snowy field, he stares at a high-fenced row of blossoming pink, white and blue flowers. The village, with four yellow houses huddled around a fenced courtyard, has snow-capped roofs protected by more bursts of blue and pink flowers. A mass of tall trees with white trunks and branches stripped of their leaves rise behind the village and pierce the bird-flecked, cloudy blue sky. The blooming flowers are incongruously but delightfully out of season, and the brightly colored painting suggests tranquility and harmony.

We also chose Milan Nadj’s Skaters in a Winter Landscape (1989), oil on glass, 9×6 inches, smaller but more vivid and detailed than Winter Landscape. Nadj was taught by Generalic and trained as a teacher. In the foreground seven children are digging and sledding in the snow, and skating on the ice of the Drava River that curves into the background. On the left and right tall trees with snowy branches spread like wings to frame their activities. Behind them a path leads past a well and up a steep hill to seven brown, steep-roofed, snow-peaked houses, one with a haystack and ladder leading to the upper story. The sunset-sky is bright orange-red, fading to misty blue, with floating cotton-ball clouds. In this busy scene, which echoes Brueghel’s Children’s Games (1560), the children’s play echoes the peasants’ work.

Milan Nadj’s Skaters in a Winter Landscape (1989)

When we tried to cross from Yugoslavia back to Austria, the Communist border guards lounged lazily around. Chatting, smoking and drinking, they waited to extract bribes that would allow a lucky car to jump the queue. As the guards obstructed traffic, the cars piled up on both sides of the border.

Jeffrey Meyers, FRSL, has published Painting and the Novel, Impressionist Quartet, biographies of Wyndham Lewis and Modigliani, and a book on the Canadian realist painter Alex Colville.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.