War games of the German intelligentsia

Wilhelm Steinitz, the chess equivalent of Karl Marx and Charles Darwin combined, was the great strategic systematic chess thinker from the latter part of the 19th century. One of the major Steinitzian strategic precepts was to delay castling in order to establish the location of the enemy king. Once that had been determined, the strategic objective was then to castle on the opposite wing and launch a blitzkrieg attack against the opposing monarch. Using this method, Steinitz won famous victories during his lengthy career against such luminaries as Zukertort, Blackburne, Tchigorin and even his successor as World Champion, the mighty Emanuel Lasker.

The theories of Steinitz were to be taken up and codified by the German grandmaster and teacher, Dr Siegbert Tarrasch. He thus earned himself the reputation of being the Praeceptor Germaniae , probably best translated as “the Lawgiver from Germany”. Tarrasch was a clear and logical mentor, but he also suffered from the dogmatism which affected both Marx and Freud. Indeed, for those who can read both Tarrasch and Freud in the original German, the stylistic similarities between these two great German-Jewish thinkers are strikingly apparent.

Thus, in his otherwise admirable manual Drei Hundert Schachpartien (“Three Hundred Games of Chess”), Tarrasch excoriates the move 3. Nd2 in the French Defence ( after 1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5) with which Tarrasch himself had previously been highly successful, on the utterly spurious grounds that 3… c5 enables Black to force the existence of an isolated queen’s pawn (IQP) and that, therefore, 3. Nd2 is “refuted!” There is no argument or discussion about it. Tarrasch used the German verb “ widerlegen ” which inescapably means “to refute.” The variation is still popular and ironically bears his name; only his “refutation” is (justly) forgotten.

Dogmatism has its place in the universal arsenal of pedagogy. Indeed, being emphatic and single-minded can assist in ramming home a message. It can, however, be taken too far. Modern teaching should be far more pragmatic and flexible.

I now digress with a brief horror story about chess coaching. A few years ago a promising chess prodigy asked to play a game against me where I would “give no quarter”. After a few moves, the prodigy simply reversed the development of a piece he had just brought into play. The game did not last much longer.

Under interrogation, the eight year old confessed that a (clearly inept) coach had prematurely deluded him into mindlessly emulating the kind of super-refined subtlety which should really have remained in the domain of those who have progressed sufficiently to comprehend the seeming paradoxes of a Nimzowitsch, a Karpov or a Carlsen.

Is chaos come again, or has it always been thus, at least since Nicolaus Copernicus proved that, far from our solar system being geocentric, the earth revolves subserviently around the sun and Charles Darwin refuted the anthropocentric thesis by demonstrating that humankind is descended from the apes ? And, if so, who has tried to combat chaos and restore or discover order?

Nearly contemporaneously with Darwin, Friedrich Nietzsche’s great metaphor to counter absence of meaning was the Eternal Recurrence ( Ewige Wiederkehr ) . Nietzsche proposed a model of the universe that repeats itself identically in infinite iterations of recycling. What has happened now has happened an infinite number of times before and will continue to replicate itself infinitely into the future. Only the Übermensch (“superhuman”) can accept this bleak scenario, yet still function as if meaning exists. Nietzsche was famously parodied by that bewhiskered philosopher, the Muskrat, in Tove Jansson’s Moomin series, that educated rodent’s favourite book, of course, being The Uselessness of Everything . Then there was Rainer Maria Rilke, whose most celebrated poem “The Carousel” , far from being purely descriptive, or an evocative paean to childhood, with its colourfully painted roundabout animals, is actually a metaphor for Nietzsche’s metaphor. Rilke ’s roundabout is going nowhere. It simply repeats its journey. The clue is in the phrase “hat kein Ziel”: it has no goal or purpose. Never before, or since, has absence of meaning been expressed with such poetic elegance.

In chess terms, Dr Siegbert Tarrasch was the thinker who did most to strive towards making sense of the chaotic cosmos of chess, where there are more possibilities than atoms in the observable universe. He postulated order, method and rules, through which to comprehend the bewildering multiplicity of potential inherent in the game. Thus there are said to be approximately 10 to the power of 81 atoms in the observable universe. To put that into context, the number (called a vigintisextillion) is the number 10 with 81 zeros behind it: 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 atoms.

This figure is only an estimation, based on a series of calculations and assumptions. It is, however, seriously dwarfed by 10 to the power of 120, the number of possible positions in chess. It was Tarrasch who yearned to make sense of this bewildering ocean of quasi-infinity.

It is relatively easy, at the same time, to admire, underestimate and to be unfair to that great German Grandmaster. Victor of numerous elite tournaments, respected writer and theoretician, challenger for the World Title and one of the five original Grandmasters, all anointed at St. Petersburg in 1914 by Czar Nicholas II, Tarrasch was, nevertheless, a prickly and dogmatic character, who made enemies almost without trying. The remaining four imperial laureates were: many times US Champion Frank Marshall, who was the original source of the grand masterly claim, and three then current and future World Champions: Emanuel Lasker, José Capablanca and Alexander Alekhine.

Tarrasch’s achievements should have rendered him immune from criticism, but he possessed a unique knack for irritating his colleagues in ways which caused permanent ruptures. For example, after just ten moves of his first game against an initially admiring Nimzowitsch, Tarrasch leant back in his chair, folded his arms and loudly announced that never before in his life had he achieved so winning a position after so few moves. Nimzowitsch (mildly paranoid at the best of times) hung on for a draw and thereafter devoted the rest of his career to opposing, undermining and refuting Tarrasch’s theories and writings about chess. In my column of May 22nd, 2021 “ Freudian Feud: Tarrasch versus Nimzowitsch ” I focused on the two great chess players’ enmity, pointing out that the playing styles of the two were not perhaps so far apart, and that the conflagration had its roots in Tarrasch’s talent to insult.

Dogmatism can have severe practical disadvantages. In the first round of the tournament at Hastings 1895, pitted against the Anglo–Irish maestro James Mason, Tarrasch had to make one last move to reach the time control, but with his time fast running out, he made no attempt whatsoever to carry out that last crucial move. Mason chivalrously warned Tarrasch that he was in danger of losing by time forfeit. Tarrasch, regally unperturbed, responded that he had completed the necessary 30 moves and he refused to budge. Predictably his clock flag fell and Tarrasch was declared to have lost on time. While Tarrasch (or, as I jocularly refer to him, Dr T) was remonstrating against this verdict, someone in the audience pointed out that Tarrasch had, in fact, written his name in the space for move one on his score-sheet; thus he had indeed legitimately lost on time. Irish fair play 1: German dogmatism 0.

At the Hamburg Tournament of 1910, “A-Team member” Dr T protested against the inclusion of the young English master Frederick Yates, on the grounds that Yates was too weak for such an illustrious field. Despite his protest, Yates was permitted to compete and did indeed finish in last place — while, however, brilliantly demolishing Tarrasch on the way.

Destiny called on Tarrasch several times, but he regularly hung up, avoiding matches for the World Title against both Steinitz and Lasker. Not until 1908, when he was in his late forties, did Tarrasch finally commit himself to a challenge. At the pre-match meeting with the reigning champion, Tarrasch is alleged to have uttered, with his customary diplomatic aplomb, the withering sentence: “ To you Herr Lasker, I have just three words to say: check and mate .“ Lasker won the match easily by 8 games to 3.

As for dogmatism, Tarrasch went so far as to condemn with “?” denoting “weak move” such mainline variations as: 1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Nf6? Tarrasch insisted that as Black’s third move (3… c5) was the only correct choice here. This latter opening variation is an aggressive bid for central space and is called the Tarrasch Defence, a variation of the Queen’s Gambit Declined. As we have seen, his annotation with the rebuke “?” also was attached to 1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nd2?, a line which, paradoxically, now bears Tarrasch’s own name: the French Defence, Tarrasch Variation.

For all his idiosyncrasies, Tarrasch patently loved chess and devoted his creative life to every aspect of the game. This love was encapsulated in his immortal aphorism: “Chess like love, like music, has the power to make men happy.” Tarrasch was writing in a male dominated, militaristic, pre-inclusive, pre-First World War society. Nowadays he would surely have replaced “men” with “people”.

Alexander Alekhine, accused of writing pro-Nazi articles in the Pariser Zeitung during the occupation, was by no means the first World Chess Champion (1927-1946 with a break from 1935-1937) to land himself in very hot water for writing something obnoxious. Emanuel Lasker champion from 1894 to 1921, had, two and a half decades before Alekhine unwisely dipped his pen in tainted Nazi ink, enraged much of the chess community of his day by his unequivocal support for the war in 1914. Strangely, Lasker was swiftly forgiven, while the anti-Alekhine boycott of 1946 certainly contributed to that great champion’s premature and tragic death, marooned without resources in Estoril in Portugal; far remote from the new centres of post war chess activity.

Before focusing on Lasker’s strident and enthusiastic summons to unleash the dogs of war in 1914, I would like to make some general comments on the relative attitude towards the gathering hostilities from the point of view of British, as opposed to German, writers and intellectuals.

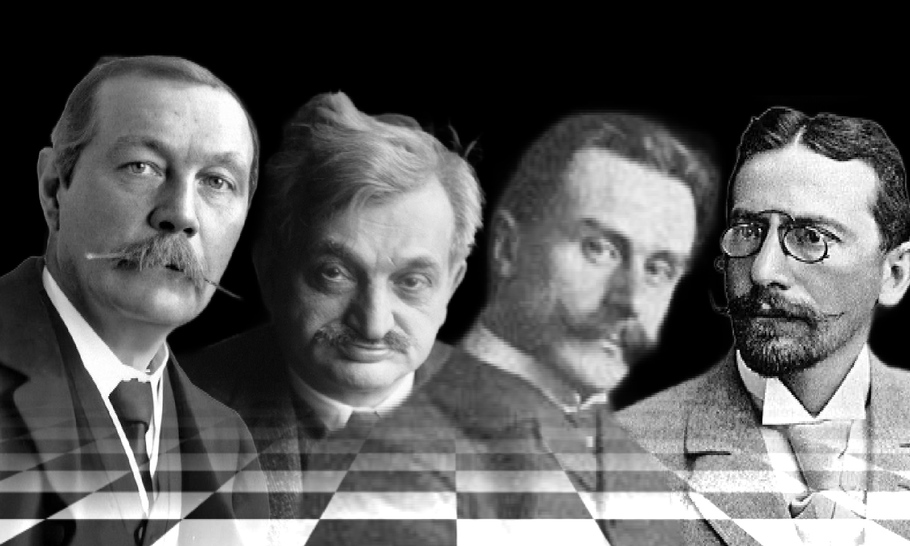

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle cited chess clearly and unequivocally only once, describing chess skill as “the mark of a devious mind”, in the Sherlock Holmes story, The Retired Colourman . The Great Detective also dined twice at Simpson’s-in-the-Strand, the traditional home of British chess, and the haunt of such greats as Wilhelm Steinitz and Howard Staunton. Indeed, a famous chess board and pieces, used by the most prominent 19th century chess champions, including also the American Meteor, Paul Morphy, can still be seen, in pride of place, at the head of the main staircase in Simpson’s. Furthermore, the “Immortal Game” of London 1851, one of the most brilliant chess victories of all time, was played on Simpson’s hallowed turf. I regard Steinitz, whom Sir Arthur must have seen at first hand, as a regular denizen at Simpson’s, as the physical template for the irascible Professor George Challenger in Conan Doyle’s Lost World and Poison Belt adventures.

As evidence of Conan Doyle’s attitude to the war, here are some words from Holmes himself in the 1917 story, His Final Bow , where Holmes turns to espionage:

“ There’s an east wind coming all the same, such a wind as never blew on England yet. It will be cold and bitter, Watson, and a good many of us may wither before its blast. But it’s God’s own wind none the less and a cleaner, better stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared .”

Sir Arthur’s stance to the war seems, from the tenor of this passage, to be one of stoic acceptance, rather than enthusiastic celebration.

When World War had broken out in 1914, Sir Arthur did his best to enlist in the army, justifying his application with the words: “ I am fifty-five but I am very strong and hardy, and can make my voice audible at great distances, which is useful at drill .” His offer was declined, but that in no way deterred Sir Arthur from contributing to the war effort in every way available to him. In fact, he had already been highly pro-active in prophylactic defence of his country, well before war had even broken out.

In particular, Conan Doyle had developed a powerful instinct that conflict was coming after a certain 1911 car rally event in which he had personally participated. That year he had been an entrant in an International Road Competition, patronised and sponsored by Prince Albert William Henry of Prussia, younger brother of the Kaiser. Described as “The Prince Henry Tour”, this was a race designed to test the quality of British automobiles against their German counterparts. The race route led the participants from Hamburg, Germany, across the continent, to London.

Conan Doyle and his wife, Jean, had signed up to form one of the British driving teams. Each of the ninety cars involved in the contest was accompanied by a military observer from the opposing squad. Conan Doyle was alarmed by the overtly hostile attitudes of many of those German observers, overhearing much confident talk from them concerning the inevitability of war.

The British triumphed in the overall Prince Henry competition, but most of the British participants came away with the reluctant, but firm, conviction that war between Germany and Great Britain was perilously near.

An identical conviction about the inevitability of war against Germany was expressed by British officers, such as Neville Harvey, who had participated in the Kiel naval regatta of 1914. The peaceful protestations of the German officer corps were universally, if privately, dismissed as entirely hollow by Harvey and his British compatriots.

Alarmed by what he had learned from the Prince Henry Tour, Conan Doyle decided to investigate German military literature. He quickly arrived at the insight that two new technological weapons, the submarine and the aeroplane, stood out as being crucial factors in the next war against a rival Great Power. He was, in particular, acutely concerned about the threat of submarines blockading food shipments and vital supplies to Britain.

Conan Doyle went on to endorse the concept of a cross Channel Tunnel, as a way of protecting Britain from this maritime threat. Burrowing between France and England, the tunnel, Conan Doyle argued, would ensure that Britain could never be isolated from the European mainland during wartime and would offer the prospect of much increased tourism revenues during times of peace.

Convinced that this subterranean resource was a necessary precaution, Conan Doyle eventually opened up his idea to the public in his favoured format of a story. “Danger! Being the Log of Captain John Sirius”, appeared in the July 1914 edition of the Strand Magazine . The narrative dealt with a conflict between Britain and a fictional nation, self-evidently Germany, but thinly disguised as Norland. This potent foe was able to inflict defeat on Britain by exploiting a tightly organised fleet of submarines, armed with the relatively new weapon of the sea-borne torpedo.

Unfortunately, Conan Doyle’s dire predictions were largely ignored, at least by the British Government. It took years for the Admiralty to conceive of the convoy system as an effective deterrent to submarine attack. German officials, however, were later quoted as saying that the idea of the submarine blockade had only entered their strategic thinking, after reading Conan Doyle’s own warnings against such an eventuality.

How much of that statement was truth, and to what extent it was propaganda, designed to cause conflict, confusion and recrimination within Britain’s press and governing echelons, is not known.

Meanwhile, in German intellectual circles, the inevitability of conflict seemed to have been widely regarded, not as a subject for warnings and defensive preparations, but, in sharp contradistinction, as a refreshingly liberating, dithyrambic event; one, in fact, devoutly to be wished.

“War! It was purification and a relief which we felt, and an incredible hope.” Thus wrote Thomas Mann about the onset of war, in the autumn of 1914 in his essay “Thoughts in Wartime”. According to Mann, war was the best thing that could happen to Germany because the “old”, civilised world, “crawling with vermin,” was at its end. Four years later, in his Reflections of an Unpolitical Man , Thomas Mann continued to assert that the war had ignited revolutionary optimism: it reinforced belief in “the human being”, in an “earthly empire of God and of love, and an Empire of freedom, equality and fraternity”.

There can be little doubt concerning the enthusiasm of German intellectuals and artists in general when the First World War broke out. Ernst Toller, for example, wrote, referring to the first month of the war, “We constantly live in a chauvinist glow. The words ‘Germany’, ‘fatherland’ and ‘war’ are magically attractive to us”. Even the usually restrained sociologist Max Weber opined gushingly, in a letter of 28 August 1914, “this war is great and wonderful”.

Now is the moment to address the literary intervention of the reigning World Chess Champion at that time. Emanuel Lasker, the German Weltmeister , who, as noted above, reigned from 1894 to 1921, was exceptionally keen for Germany to enter the war. This seems at odds with his prior internationalism, for he had spent much time in Britain, even representing England, rather than Germany, in the great Hastings International Tournament of 1895.

Lasker’s immediate response to the outbreak of hostilities was to publish a series of distinctly gung-ho pro-war articles in the autumn of 1914. In one, from 13th September, he stated that: “the goal of occupation and administration of France by Germans is as sure as mate by rook and king against king”. This is very much a beginners’ checkmate since it is so simple. Thus Lasker succeeded in insulting the French, even more than alienating his former friends, the English, whose flag he had once espoused. Other pieces of wit and wisdom from the World Chess Champion amounted to additional facile analogies between standard chessboard tactics and real battlefield operations. Lasker may have thought he was being clever, but it all comes across, not just as infantile, but also callous, implying that the casualties of wooden warriors in chess somehow equated with flesh and blood slaughter at the front.

One staunch Englishman, a Mr. Henry Butler, until that moment Lasker’s friend and a leading official of the Brighton Chess Club, which had organised his King’s Gambit match against the Russian grandmaster Tchigorin in 1903, was so incensed by the articles, that he smashed through a large portrait of Lasker by jumping up and down on it with both feet.

It seems strange that even such a cosmopolitan champion as Lasker — who had dedicated his entire professional career to the virtual warfare of playing chess around the world from London to Paris, St Petersburg, Moscow, Vienna, Berlin, New York and so on — should have become so fervently bellicose. Lasker’s stance, however, was very much the prevailing norm amongst German intellectuals and the educated elite of his day. The “ Aufruf an die Kulturwelt ” of 4 October 1914, was a further pro-war tract, a summons to arms for the world of German culture, signed by no fewer than ninety-three German intellectuals, scientists and artists, including a number of Nobel prize winners, such as Max Planck. Thomas Mann in his thoughts on the war, “ Gedanken im Kriege ”, published sixty days after the declaration of war, in the Neue Rundschau , lauded the “cleansing of the soul” and “moral regeneration” which the conflict would mystically conjure into being.

I believe that such a mass corralling of the intelligentsia, in order to endorse a bloody war, would have been unthinkable in England. There were, of course, isolated cases of early enthusiasm (Kipling springs to mind) but I think that the Conan Doyle attitude of “we don’t want to fight, but…” was far more typical. Indeed, a positive herd imprimatur by great minds to beckoning carnage would have resulted in public derision, had some delusional bureaucrat tried to orchestrate something along similar lines in England.

I leave the following astonishing last words to the self-same Thomas Mann, whose pro-war diatribes also contained some choice opinions about “inferior “races. Just the sort of thing which got Alekhine into trouble. Mann’s utterances cast an extraordinarily unflattering searchlight onto the mindset of German intellectuals of that time, as first Europe, and then much of the rest of the planet, burst into flames. Mann wrote in his Observations of an Unpolitical Man, coming out as late in the war as 1918:

“ There are highly political nations — nations that are never free of political stimulation and excitement, that still, because of a complete lack of ability in authority and governance, have never accomplished anything on earth and never will. The Poles and the Irish for example. On the other hand, history has nothing but praise for the organising and administrative powers of the completely non political German nation .”

Thus Thomas Mann. Who would have believed it, but if Mann could indulge in such outrageous prejudice, it was merely a short step for Lasker to join him. It is a source of amazement to me that such, in other respects, sophisticated intellectuals, even men of genius, as these could descend to such crude and banal warmongering.

Interested readers may wish to consult my review here of the new book by my fellow contributor to TheArticle, Jeffrey Meyers: Parallel Lives: From Freud and Mann to Arbus and Plath , which discusses Mann and other writers.

Parallel Lives: From Freud and Mann to Arbus and Plath by Jeffrey Meyers is published by LSU Press, and is available through all good booksellers, including Amazon.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.