Who were the Nazis? A new landmark work

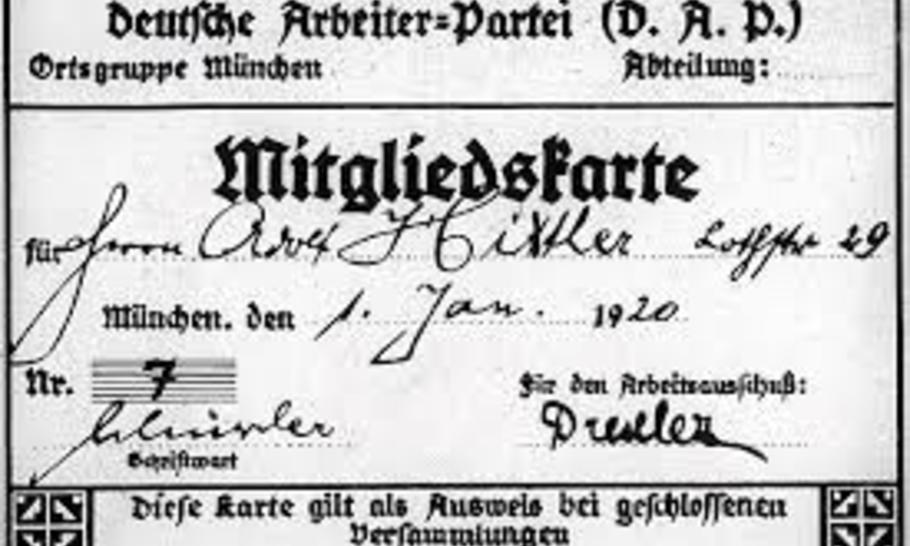

Forged copy of Adolf Hitler's Nazi membership card, which changes number 555 to 7

Who actually joined Hitler’s party? How many Germans became members of the party that styled itself as the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), abbreviated to “Nazi”? Were Germans forced to join, as some members claimed after the war? Which social classes did the party draw its members from? And why did members join the party?

On this subject, the renowned German political scientist and contemporary historian Jürgen W. Falter has published a new book, which has just been released in English translation by Routledge: Hitler’s Party Comrades. The NSDAP Party Members 1919-1945.

On January 30, 1933, the day Hitler was appointed chancellor, the NSDAP counted 900,000 members. By the time the Third Reich collapsed in 1945, this figure had swelled to almost nine million. Or, to put it another way, roughly one in seven eligible voters in Germany was a party member by the end of the war.

After its reformation in 1925, the NSDAP only accepted new memberships from the general public for about a combined twelve of the following twenty years. Time and again, membership recruitments were suspended. But why? Well, in Mein Kampf and a series of early speeches, Hitler had already developed the theory of the “historical minority,” meaning that only historical minorities make history. The historical minority must comprise “courageous” individuals who are prepared to make great sacrifices, both personally and for their careers. According to Hitler, before a political movement comes to power, during the period when it is fiercely resisted by the “establishment system” and other opponents, it will inevitably only attract “brave” members. Once the party has seized power, however, Hitler warned in Mein Kampf that increasing numbers of opportunists would join the party in pursuit of their own private advantage or to further their own careers. And in fact, that is precisely what happened.

After January 30, 1933, opportunism and career ambitions played an increasingly key role in the recruitment of new members: between January 30 and the end of April 1933 alone, 1.75 million new members signed up as members of the NSDAP, at which point new memberships were suspended. But, in spite of the regular recruitment stops, the party’s membership continued to grow strongly.

After the war, many members stated that they had been forced to join the party. Despite his extensive analysis, Falter finds no evidence to support such claims. In fact, members were fully able to leave the party and cancel their memberships. A total of 760,000 members resigned from the NSDAP between 1925 and 1945, 250,000 before January 1933 and almost half a million members left the party during the Nazi dictatorship.

For this study, Falter analyzed by far the largest and most comprehensive sample from the two central NSDAP membership card indexes. As Falter demonstrates, a disproportionately large number of white-collar professionals and civil servants joined the party after January 30, 1933. Nevertheless, the proportion of blue-collar workers in the NSDAP was always far higher than has been previously assumed. Similar to the party’s voters, roughly 40 percent of the NSDAP’s members were working class. In terms of its social composition, the NSDAP was neither a workers’ nor a middle-class party: it was, rather, a “catch-all party of protest”. Men were much more strongly represented in the party than women, a fact that also applied to other political parties in Weimar Germany.

Where the NSDAP did differ from other parties, however, was in the youthfulness of its supporters. In the early years, most of the party’s new members were under the age of thirty, including many who were even under the age of twenty-five. Then, as the party got older, so did the average age of its members. In response, after the second suspension of new memberships in 1942, only graduates of the Hitler Youth (HJ) and the League of German Girls (BDM) were accepted, along with war survivors and those who had left the Wehrmacht. The party was to remain young.

There existed no single, all-encompassing motive to become a National Socialist. Falter shows that 50 percent of those over the age of forty but only 26 percent of those between the ages of twenty and forty cited hostility toward Jews as a primary motive for joining the party. There is no doubt that the NSDAP was a thoroughly anti-Semitic party, but Hitler knew that anti-Semitism would only mobilise a minority of voters. In contrast to the early days of the NSDAP, Hitler did not primarily focus on anti-Semitic motives in his speeches at the end of the 1920s. Instead, he devoted far greater attention to his social promises. As Falter writes: “Hand in hand with the ideal of the Volksgemeinschaft (‘national community’), there was also often a desire to abolish privileges and the established class system. The combination of nationalism and socialism in the name, combined with the party’s policy program, were major factors boosting the NSDAP’s attractiveness.”

Rainer Zitelmann is the author of Hitler’s National Socialism (updated edition 2022).

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.