Chess: Feasting with Grandmasters

(Shutterstock)

How do chess Grandmasters fuel their little grey cells to achieve maximum efficacy during their often lengthy chess board battles? In previous columns I have argued the case for a marine based diet, rich in brain foods, such as Omega-3 fatty acids, DHA (Docosahexaenoic acid) and EPA (Eicosapentaenoic acid), as advocated by Professor Michael A. Crawford Director of the Institute for Brain Chemistry and Human Nutrition, at London’s Imperial College. Indeed, during the Howard Staunton Memorial Tournament, which I organised with one of Britain’s most distinguished artists Barry Martin at Simpson’s-in-the-Strand, Britain’s foremost grandmaster, Nigel Short MBE, was so convinced by Professor Crawford’s opening oration, that he adopted an entirely piscine regime during the competition, which he then proceeded to win.

There are, though, alternatives. Garry Kasparov, for example, favoured the demolition of a large rare-cooked steak about one hour before his games. Most other elite grandmasters, not to mention we lesser mortals, might succumb to drowsiness after a large meal, becoming inattentive during the opening phase of a game. Writing from bitter personal experience, I can assure readers that even Grandmasters can go catastrophically astray during the initial few moves, if the brain is not fully engaged.

Kasparov’s secret antidote to the dangers of mental torpor in the opening moves of a game was that he knew his openings so well that he could navigate such dangerous stretches on autopilot. Kasparov could then rely on the fact that the mental energy provided by the steak would kick into action in the early middle game, when he needed it most.

Reigning World Champion Magnus Carlsen favours Lebanese and Chinese cuisine, with a considerable trend towards vegetarian dishes, and in general the top modern players are quite ascetic in their habits.

Back in the day, chess players used to feast more extravagantly than our modern counterparts and, on the whole, were more friendly towards strong spirits, gourmandising and reliance on nicotine.

For example, there was the Georgian method, which raised conspicuous consumption to a whole new level of intensity. In 1974 I competed in a Grandmaster level tournament in Tbilisi, capital of Soviet Georgia. The rounds were punctuated by three evening banquets, to which all contestants were invited. A long central table was always laden with Georgian delicacies, fuelled by heroic quantities of Soviet caviar, blinis and pelmeni, all washed down with vintage champagne and Russian brandy or vodka. To ensure that sufficiently gargantuan measures of alcohol were being consistently consumed, the hosts always appointed a table captain, or Tamada, to deliver suitably elaborate toasts, whereupon the guests were expected to drain their glasses, in expectation of a top-up for the inevitable next toast.

My Georgian friends explained that their curative antidote, after such record breaking volumes of food and accompanying lubrication, was to struggle into the garden, dig a hole in the ground, lie over it, with space for the belly in the hole, and cry out a promise to God that this would be the last time for such super-over-indulgence… until the next time, that is.

After the third and final banquet, I departed in the early hours with my friend, Icelandic Grandmaster Guðmundur Sigurjónsson. We scoured the streets for a cab in vain, until I saw a car glide sedately into view, with a flashing green light and a seemingly smartly dressed gentleman in a peaked hat at the wheel. I promptly hailed the long awaited cab, in spite of Sigurjónsson nervously tugging at my arm and urging me to desist.

The car pulled over, and with my Icelandic companion becoming ever more tense, for reasons which I utterly failed to comprehend, I addressed the driver, stating in my vestigial Russian: “Gastinitsa Iveria pojalsta” or words to that effect, thus indicating that he should please drive us to the Hotel Iveria, where we were staying. On being informed that we were two chess grandmasters in need of a lift, the driver politely saluted, ushered us into car and duly headed towards The Hotel Iveria. The siren, which suddenly sounded, should have given me the first clue, plus the fact that we were sitting in a cage, unusually located at the back of the cab. As alert readers will have by now deduced, I had hailed not a taxi, but a police car!

In foreign tournaments the only chess banquets I have encountered, to rival those in Georgia, were those served up in so called government rest houses in Shanghai, Guangzhou and Beijing. The most lavish consisted of nineteen separate courses, fish carved into the shape of dragons, crispy duck, dried baby scorpions, and instead of vodka, a distilled Chinese spirit called Maotai (which seemed to the British delegation to resemble a peculiarly potent brand of rocket fuel) – no wonder the government needed a rest after such repasts.

England in the Middle Ages witnessed some spectacular feasts, with up to forty deer and a thousand chickens regularly sacrificed on the twin altars of Dionysus and Hestia, but such excess had little or nothing to do with chess, apart from the presence of bishops, or perhaps Grandmasters of military crusading orders.

Generalities apart, one of the most elaborate medieval feasts for which there is specific hard evidence (such as actual accounts of expenditure) was the installation of the new Archbishop of York, the aristocratic George Neville, brother to “Kingmaker” the Earl of Warwick, in 1466. It included as main ingredients: 104 peacocks, 4,000 ducks, 204 cranes, 400 herons, 1,000 sheep and 104 oxen.

High-status food tended to be separately served to high-status people, of course (such as the items at the start of the above list) and was often recorded as especially impressive. As historian Richard Eales has noted, it’s not too clear that the participants did much afterwards – or if they did play chess they would have been utterly oblivious to their results.

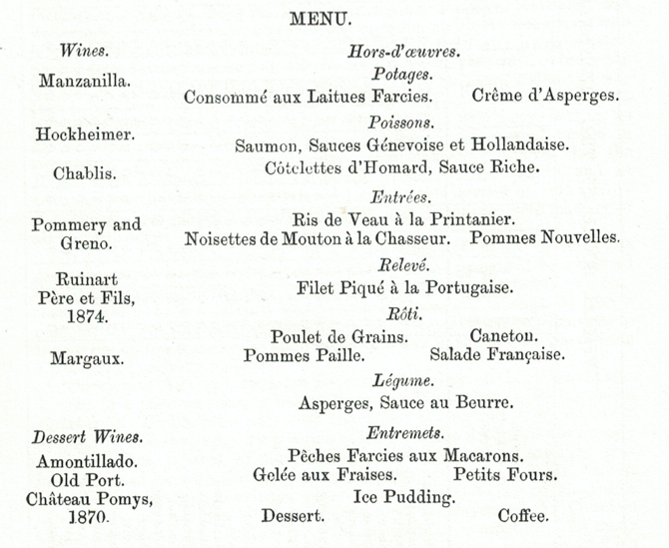

The most extravagant banquet ever held in the UK in connection with chess was staged during the London 1883 tournament, which saw Johannes Zukertort triumph, ahead of such luminaries as Wilhelm Steinitz, Mikhail Tchigorin and our own Joseph Henry Blackburne. Here is that lavish menu from the book Games Played in the London International Chess Tournament, 1883 edited by James Innes Minchin.

Although the tournament was held in London, the menu was doubtless deemed to increase in prestige if rendered in French. Here is my translation of the menu into English:

| Wines | Food |

| Hors-d’oeuvres | |

| Soups | |

| Manzanilla | Clear soup with stuffed lettuce |

| Manzanilla | Cream of asparagus |

| Fish | |

| Hockheimer | Salmon with Genovese and Hollandaise sauces |

| Chablis | Lobster cutlet with rich sauce |

| Starters | |

| Pommery & Greno | Sweetbreads with Spring vegetables |

| Noisettes of mutton in huntsman’s style with new potatoes | |

| Second Starter | |

| Champagne Ruinart 1874 | Portuguese style larded fillet of beef |

| Roasts | |

| Chateau Margaux | Corn-fed chicken with straw potatoes |

| Chateau Margaux | Roast duckling with French salad |

| Vegetables | |

| Asparagus with butter sauce | |

| Entremets & Desserts | |

| Amontillado Sherry | Stuffed peaches with macaroons |

| Old Port | Strawberry jelly & Petits Fours |

| Chateau Pomys 1870 | Ice Pudding |

| Chateau Pomys 1870 | Desserts & Coffees |

It is said, possibly apocryphally, when the toast to the best chessplayer in the world was pronounced, that both Zukertort and Steinitz leaped to their feet.

In spite of such culinary excursions and adventures, there can be no doubt that the dining establishment which has entertained by far the greatest number of chess Grandmasters, whether in the UK or worldwide, is that self-same Simpson’s-in-the-Strand (pictured), where, as we have seen, Nigel Short converted, if briefly, to a DHA enriched diet of lobsters, oysters and Dover sole, in order to boost his little grey cells for the chessboard combat to come. Simpson’s standard fare focuses traditionally on roast lamb and beef, carved at the table from mobile silver trolleys.

During the 19th century Simpson’s was, in fact, the world’s greatest chess club, with coffee and cigars proving as popular as roast beef and lamb. A famous chess board and pieces situated at the top of the main staircase still commemorates the exploits on the 64 squares of such chessboard immortals as Howard Staunton, Adolph Anderssen, Paul Morphy and Emanuel Lasker. On my 50th birthday the genius loci Brian Clivaz (now of L’Escargot in Soho, London) invited me to play a couple of games on this hallowed chessboard turf, and generously inscribed my name on the plaque, along with the gods of the game.

Simpson’s was the location of this week’s masterpiece, known as The Immortal Game, won by Anderssen in 1851. So impressed were both the loser and the onlookers that top-hatted runners were despatched down the Strand to telegraph the moves to the Café de la Régence in Paris, the then epicentre of Gallic chess activity, the original, sadly, no longer being extant. Here is a description of The Immortal Game on YouTube for chess fans with an explanation of the moves, tactics and strategy.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle can be added to the illustrious list of patrons who frequented Simpson’s, and he rewarded Sherlock Holmes with “something nutritious” there after solving the cases of The Illustrious Client and The Dying Detective. It is my belief that Sir Arthur observed the chess champion Wilhelm Steinitz in action at Simpson’s, borrowed his shaggy hair and beard, huge domed forehead and short, but muscular stature, to describe the epitome of the scientific adventurer, Professor George Challenger, from his novels, The Lost World and The Poison Belt.

I conclude with a brilliant tour de force by the winner of that world class tournament, held at London in 1883. Here is the game of Johannes Zukertort versus Joseph Henry Blackburne in 1883, the absolute pinnacle of Zukertort’s chess creativity.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout the pandemic. So please, make a donation.