How the battle to abolish war goes on

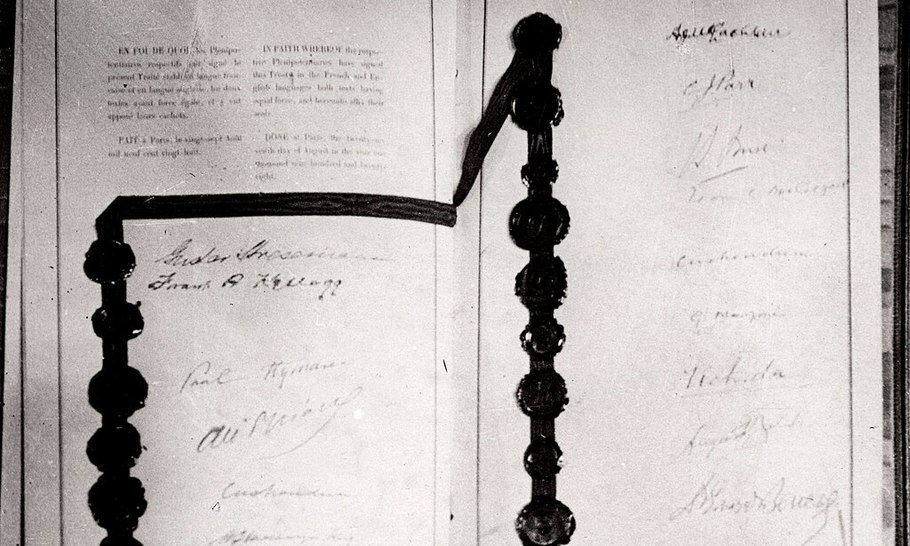

Briand-Kellogg Treaty, with signatures of Gustav Stresemann, Paul Kellogg, Paul Hymans, Aristide Briand, Lord Cushendun, William Lyon Mackenzie Kin...

The quarterly newsletter Abolish War, produced by the Movement of the same name (MAW), regularly comes through my letter box. The Movement to Abolish War’s founding chairman, the late Bruce Kent, came to national prominence as General Secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) in the 1980s.

Abolish War seems unworldly, almost quixotic. Who could imagine its mission to be achievable? The short answer is the 10,000 people from many nations gathered in the Hague between 11-15 May 1999, the centenary of Czar Nicholas II’s 1899 Hague Peace Conference. In recognition of the terrible toll of war in the 20th century, they produced an Agenda for Peace and Justice for the 21st Century.

Presiding over the proceedings was the scientist Sir Joseph Rotblat FRS who, in 1944, had refused to work on the atomic bomb. Attending were Archbishop Desmond Tutu and other Nobel peace laureates. MAW was a response by British peace organisations to the Hague conference. The movement began work in 2021 following the conference’s comprehensive agenda: peace education covering the arms trade, conflict resolution, humanitarian and human rights law, bans on child soldiers and land mines.

A better known example would be the Agenda for Peace and Justice for the 21st Century, the Kellogg-Briand (Paris Peace) Pact, a turning point in international law. The Minnesota Senator Frank B. Kellogg, a lawyer, was US Secretary of State 1925-1029. Aristide Briand served as French Foreign Minister during the First World War and from 1921-1929. The Pact began life as a treaty between the USA and France, but was signed on 27 August 1928 in the Quai d’Orsay by 15 nation states, including the USA, UK, France, Japan, and Germany. By the end of 1929, 57 states including China and the Soviet Union had signed.

Article I stated: “The High Contracting Parties solemnly declare in the names of their respective peoples that they condemn recourse to war for the solution of international controversies, and renounce it, as an instrument of national policy in their relations with one another.” Article II: “The High Contracting Parties agree that the settlement or solution of all disputes or conflicts…. shall never be sought except by pacific means.” The outlawing of war had been adopted by governments as a principle. Practice would take considerable time.

As the much acclaimed book The Internationalists: and their plan to outlaw war by Oona A. Hathaway & Scott J. Shapiro (Allen Lane, 2017), makes clear, the Pact marked a new stage in the development of international law, the beginning of a shift from one international order to another.

The seminal work of the Dutch lawyer Hugo Grotius (1583-1645), known for his elaboration of just war theory, is acknowledged as the foundation of the Old Order of international law. He saw war as a legitimate means of combating malfeasance abroad: against aggression, to recover debts, righting wrongdoing or resolving disputes. He recognised that every belligerent asserted they had just cause and believed, to avoid chaos, the outcome of each war had to be accepted, allowing – not incidentally — trading companies to retain booty captured by piracy (Grotius was hardly otherworldly). In short, in Grotius’ Old Order, Might was Right. The Kellogg Briand Peace Pact, with its 57 signatories, denied these basic premises.

The Pact’s intellectual origins lay outside government. Salmon Levinson (1865-1941) was a successful corporate lawyer, a friend of the eminent American philosopher, John Dewey. Arising in the context of the First World War, Levinson’s fundamental legal assertion was that wars should not be considered “upon the same plane of legality without any regard to their origins and objectives”. “We should have, not as now, laws of war, but laws against war; just as there are no laws of murder or of poisoning, but laws against them”. The League of Nations — established in 1920, moribund from 1939 and dissolved in 1946 — was attempting to regulate the conduct of wars and promote disarmament, whilst Levinson flooded the US with pamphlets describing inter-state wars as a public crime, and calling for their outlawing.

Levinson was not a lone campaigner. In 1924, a Canadian Quaker, James Thompson Shotwell, Professor of the History of International Relations at Columbia University, New York, gathered a group of scholars to create a draft disarmament treaty. In charge of research at the Carnegie Endowment for Peace, he adopted the position that “aggressive war is an international crime”. In April 2027 Shotwell lobbied Briand. After much diplomatic manoeuvring between France and the USA, Levinson’s and Shotwell’s parallel initiatives bore fruit in the 1928 Peace Pact. It inaugurated a New International Order — though war was far from outlawed in practice.

The Internationalists notes that the final paragraph of the Atlantic Charter (April 1941), added by President Roosevelt, asserted that all the nations “must come to the abandonment of the use of force”. Not long after Pearl Harbour (7 December 1941) Churchill, staying in the White House for three weeks over Christmas, and the Allied Powers, signed a new “Declaration of the United Nations”, rejecting war and conquest; 22 other countries followed suit. Less than four years later in 1945, 51 nations signed the UN Charter. Shotwell had pushed hard for the provisions of the Peace Pact to form the core priority of the United Nations in a post-war organisation. The Charter’s Preamble committed to saving “succeeding generations from the scourge of war”. Shotwell’s vision was shared by the dying Roosevelt. The aim of abolishing war did not then seem quixotic.

The first session of the UN General Assembly held in Methodist Central Hall, London, in January 1946, was a pivotal moment for international law. The UN provided a means not only to prevent, but also to punish wars of aggression, not unilaterally as in the past, but by interventions authorised by the Security Council – though Stalin’s blocking veto hobbled it — and by what Hathaway and Scott call “outcasting”, meaning primarily the development of progressively effective sanctions.

The Internationalists offers a plausible narrative and statistical case that the slow-burning 1928 Peace Pact was behind the massive drop in inter-state wars by the 1950s — though subsequently decolonisation, amongst other factors, inaugurated a period of intra-state conflicts, some genocidal. Today we might argue that we are seeing a reversion globally to the Old International Order. Worse. Grotius initiated a systematic framework for international law, which key actors are now dismantling.

The book doesn’t reflect on, though does chronicle, the extraordinary part played in the pursuit of peace by civil society organisations and leaders. And the outstanding role of a few individuals and organisations. Sadly, there is no room to celebrate two other outstanding lawyers of great contemporary significance, Hersch Lauterpacht, 1896-1960 – criminality in aggressive war and Raphael Lemkin, 1900-1959 – the Genocide Convention.

If reinforcing international law and peace-building is indeed being reversed, we need to value and respect the efforts of the dedicated, mostly hidden, peace diplomacy of the Vatican and the peace organisations such as Pax Christi and the Movement for the Abolition of War, not treat them as quaint eccentrics. We should listen seriously to what they have to say, for hope lives on in the enduring conviction of the few, and not naively, that humanity can, and must, pursue alternatives to war.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.