Modi Underneath: the life and work of Amedeo Modigliani

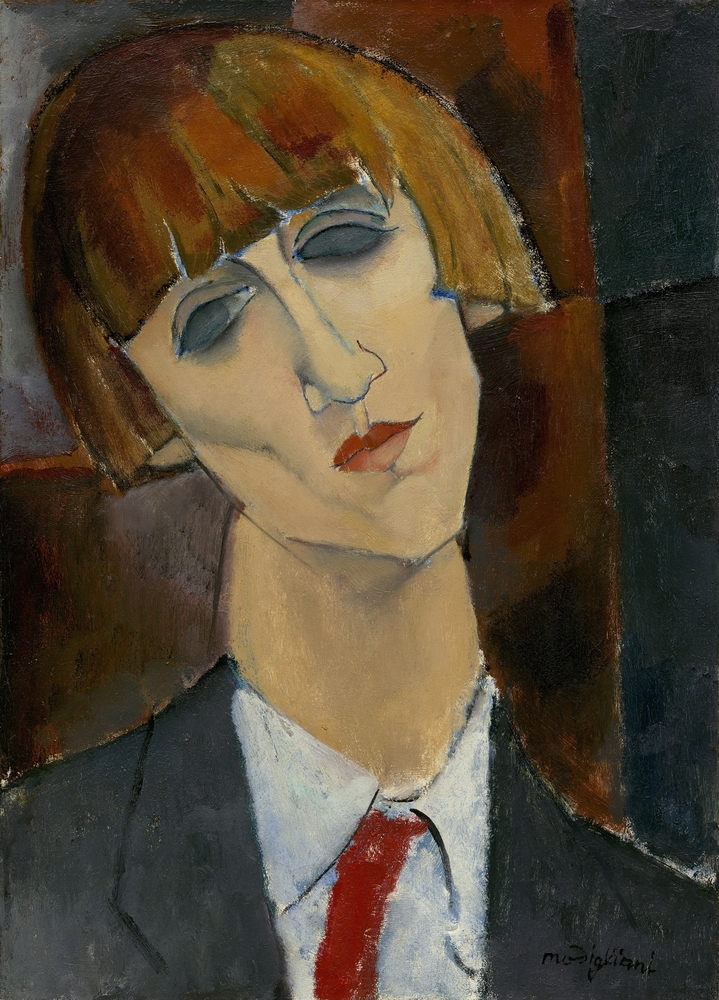

Woman with Red Hair, by Amedeo Modigliani, 1917, Italian painting, oil on canvas. This is one of several 1917 portraits, painted in a stylized abst...

Focusing on the collection of twelve paintings and one sculpture by Modigliani in the Barnes Foundation, Modi Up Close (ed. Barbara Buckley et al. Philadelphia: Barnes Foundation, 2022) uses scientific research to show how the artist constructed and composed his paintings and sculpture. The authors emphasise the paintings as physical objects, not works of art, and analyse what’s below and behind them, not what is visible. Their book should have been called Modi Underneath. Few readers will be interested in the extremely specialised technical details of canvas and paint, of wooden structures on the back of the paintings. This is a dull book on a charismatic artist.

JUAN GRIS, by Amedeo Modigliani, 1915, Italian modernist painting, oil on canvas. Portrait of Spanish Cubist painter was made in Paris during WW1 (Shutterstock)

The authors claim that the technical analysis of Modi’s materials and methods offers fresh perspectives and new insights, and explains “fascinating mysteries.” But instead of making new discoveries, this volume confirms in massive detail what’s already known: that Modi (as he was called) drew the subject on canvas before painting it, painted over old pictures by other artists, used their textures and colours to enhance his own work, and jabbed the surface with the end of his brush. He worked from models and began with preliminary sketches, was a skilled colourist and had distinctive brushstrokes. At night he stole blocks of limestone from building sites and wheeled them back to his studio in a barrow. He marked the stone with paint to guide his direct carving. Influenced by the non finito of Michelangelo’s Captive, he left numerous tool marks and unfinished surfaces.

This heavy five-pound book is marred by at least two dozen repetitions as different teams of contributors weigh in on similar subjects and describe the same techniques. In a weird mistake, the authors, following the doubts of an imperceptive scholar, vaguely call one work Modi Underneath: the life and work of Amedeo Modiglianithough it obviously portrays Modi’s common-law wife Jeanne Hébuterne.

JEANNE HEBUTERNE, by Amedeo Modigliani, 1919, Italian modernist painting, oil on canvas. Hebuterne, the artists 21 year old mistress, was pregnant with their second child (Shutterstock)

Influenced by trendy notions instead of looking carefully at the pictures, the authors repeatedly claim that Modi’s Antonia (1915, Orangerie, Paris) is Cubist and his Reclining Nude (1919, MOMA) “also suggests the influence of Cubism, in particular Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” But Modi’s languid, calm, sleeping, sensual nude is completely different from Picasso’s Dionysian, barbaric, standing, African-mask figures. Modi was not a follower of Cubism and said: “I’m ten years behind them.” Picasso fractured the traditional portrayal of the nude; Modi followed and enhanced that tradition.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Pablo Picasso, 1907, oil on canvas. (Shutterstock)

The authors also mistakenly claim that Modi’s Amazon (1909, private collection) was influenced by Matisse’s Fauve palette. But the comparative painting they reproduce illustrates the difference, not the similarity, of the works. The Matisse has bright blue, pink, orange and red colours, and a broad green stripe running down from the woman’s hairline to her lip. Modi’s picture, by striking contrast, shows the influence of German Expressionism in the high cheekbones and angular face, the masculine dress and arrogant pose of the baroness. She has fine skin; large, almond-shaped, widely spaced eyes; a pert nose and sensual lips. She wears a high stiff collar and dark tie; a tawny, lion-coloured, well-cut riding coat with broad shoulders and nipped-in waist. Assuming an aristocratic stance and strongly silhouetted against the dark background, she puts her gloved hand on her hip, turns her body to the left, slightly tilts her head and looks disdainfully down at the viewer. The baroness’s lover reported, “The portrait seems to be coming along well, but I’m afraid it will probably change ten times again before it’s finished.” The baroness didn’t like the picture, especially after Modi changed the colour of her coat from red to yellow, and rejected it. In 1913, four years later, she changed her mind and tried to buy it.

Much more could be said about Modi’s life and the paintings discussed in this volume. Modi (1884-1920) and his close contemporary Egon Schiele (1890-1918) both led impoverished, scandalous, tormented and tragic lives, and their early deaths were immediately followed by the deaths of their pregnant wives.

Madame Kisling, by Amedeo Modigliani, 1917, Italian painting, oil on canvas. Moise Kisling lived in the same Paris building as Amedeo Modigliani in 1916. This painting is likely a portrait of Kisling (Shutterstock)

The authors of this volume don’t mention the powerful influence of the Japanese courtesans painted by Utamaro (c.1753-1806). Both artists portray women with high dark hair, tilted heads, long oval faces, lofty foreheads, high arched eyebrows, empty close-set almond eyes, long narrow noses, small pursed lips, swan necks, exposed breasts and elongated bodies.

Modi’s Portrait of Paul Guillaume (1915, Toledo) is a stylised but clear likeness of his handsome and dapper young patron. His large square head, supported by a cylindrical neck, is tilted to the right. His rug of hair is neatly parted, his eyes are black and blank. The triangle of his nose matches the triangles of his moustache (separated in two elegant halves) and of his half-open mouth (with feral teeth). His dark tie with beige streaks extrudes from his stiff white collar. Modi vainly hoped this arrogant and rather supercilious dealer would guide him to his long-awaited wealth and fame. It’s worth noting that Zeppo Marx and then the Hollywood director William Wyler both owned a portrait by Modi.

The figure in The Little Peasant (1918, Tate) is seated on a wooden chair, facing the viewer, with a bluish green wall and closed gray door behind him. He has a round tanned face, ruddy cheeks, small blue eyes, tiny red mouth and a bump on his chin. He wears a brown velour hat (unusual in Modi’s portraits), a white, collarless, too-tight, hand-me-down shirt pulled open on his chest, and an olive green suit with a too-small vest drawn open on his belly. His working trousers have patched knees and his large farmer’s hands lie stiffly on his lap above his open legs. Grateful for a rest, and blending beautifully with the background, he seems calmly resigned to a life of arduous toil.

The Little Peasant, by Amedeo Modigliani c.1918 (Shutterstock)

The Girl with a Polka-Dot Blouse (1919, Barnes) has thick brown hair parted and combed across the top of her head, high forehead, long oval face, deep blue eyes, closed full red lips and straight column-like neck. She wears a charming blue polka-dot blouse and thick blue bow that echo the colour of her eyes, a black belt and billowing raspberry skirt. She’s rather stiffly seated, facing the viewer, with hands clasped on her lap and a contented expression that suggests she’s about to leave for a party. The piercing blue eyes of the little peasant and polka-dot girl seem to show the cerulean sky shining through their skulls.

Girl with a Polka-Dot Blouse, by Amedeo Modigliani 1919 (Shutterstock)

The authors in this volume note that Nude with Coral Necklace (1917, Oberlin College) has his characteristic “up-close presentation of the body and its arrangement from left to right, the sharp contours, the compressed space.” One could add that the ruddy-cheeked model, extended on white drapery, has one blank and one half-closed eye, and wears a coral necklace that precisely matches the rosy medallions at the end of her breasts. She leans on her right arm and with her left hand seductively covers part of her pubic hair. The authors mention François Boucher’s bare-bottomed Odalisque (1745) as the model for one of Modi’s nudes. But they don’t explain that all his luscious nudes, single figures without symbolic attributes, were modelled on classic paintings by Giorgione, Titian, Velázquez, Goya and Manet.

In Nude (1917, Guggenheim) the model is asleep, but available, on a huge white divan with both hands folded behind her head (which raises her full breasts), her nose parallel to the bed, her belly softly sloping below her indented navel, her armpits anticipating the triangular mound of Venus, bare on one side and in full view.

The Reclining Nude (1917, Metropolitan Museum) is the most sensuous of all. She’s seen close-up and from above, as if the viewer were gazing down at her before joining her in bed. Clearly outlined, she lies on a background of distinctly decorated colours: a lush red divan with yellow curlicues, huge white pillow and dark russet background. Her face is exceptionally glamorous and appealing. She has thick curly hair, long thin eyebrows, large dark eyes, charming nose, full sensual lips and receptive open mouth. Her budding nipples, warm radiant skin, full thighs and slightly open legs suggest pleasures just realised or soon to come.

RECLINING NUDE, by Amedeo Modigliani, 1917, Italian modernist painting, oil on canvas. This is one for several dozen nudes Modigliani painted between 1916 and 1919 on commission from his dealer (Shutterstock)

Modi’s Self-Portrait (1919, São Paulo), though painted realistically, is not a close likeness. He gives himself a brush and palette with a blurred range of colours: green, gray, black, blue, white, red, tan and orange, a contrast to the muted tones of the portrait, which he uses for no other artist he depicted. Seated erect and sideways on a thin wooden chair that scarcely supports him, he tilts his head back and looks to his left. Bundled up against the wintry cold of his studio, he wears a heavy grey shawl, velvety russet jacket and black trousers. He has thick brown hair, a long straight nose and handsome delicate mouth. His brown eyes, as if he couldn’t bear to look at them, are blank. In his last testament, his old swagger is gone. He appears pale and sickly, and seems to accept his tragic fate. In his more revealing last photo, with sharp lines on his face and deep pouches under his eyes, Modi looks a decade older than thirty-five. Shabby, ravaged and sad, he seems to be in pain and aware of his impending death. Though Modi did not live to fulfil his artistic destiny, he left some of the most beautiful and original paintings of the modern era.

Self Portrait, by Amedeo Modigliani 1919 (Shutterstock)

Jeffrey Meyers, FRSL, has published Painting and the Novel, a life of Wyndham Lewis, Impressionist Quartet and a book on the realist painter Alex Colville.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.