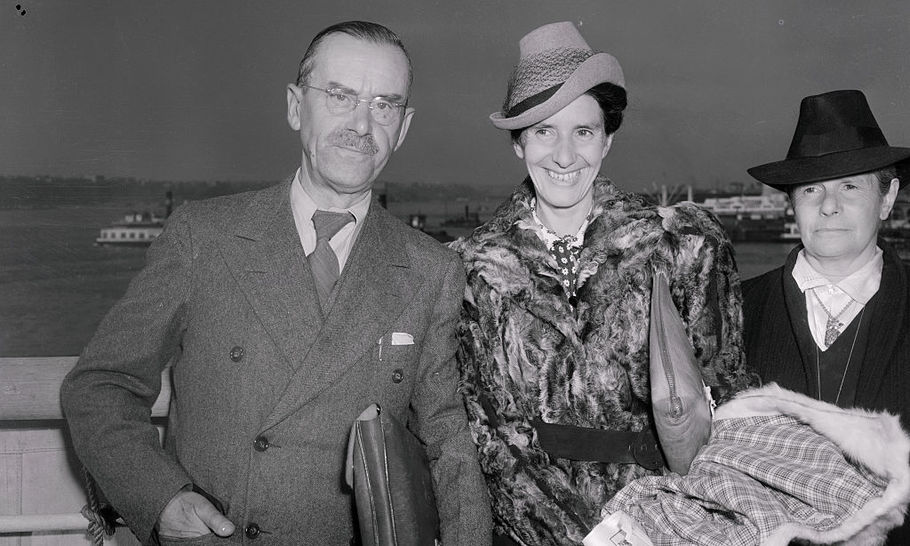

Thomas Mann: The Princeton Years

Photo by George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images

When Thomas Mann taught at Princeton University (September 1938 to March 1941) he had a privileged status and a particular role to play. The Nobel Prize-winner and world famous novelist, the leading representative and most outspoken of the anti-Nazi émigrés, symbolised in America the best in German culture. In exile the militant humanist and idealistic Kulturträger proudly but truly said, “Where I am, there is Germany.” During the approach and outbreak of World War II, he made arduous lecture tours to advocate democratic government and oppose Hitler. With great generosity he helped other émigrés, and cared for his own dispersed and often endangered family. Helped by wealthy and influential patrons Mann was able to maintain his dignity, recreate the comfortable patrician life he had enjoyed in his native land and prove that it was still possible to write great German works in a free country.

Mann’s patron Caroline Newton had briefly met him through Jakob Wasserman, whose novels she’d translated, in Berlin in 1929. Eight years later, when Mann was living in exile in Küsnacht, near Zurich, Newton approached Christian Gauss, the dean at Princeton. He was eager to help and exclaimed: “His life is not safe in Switzerland. The Nazis will murder him, stage an automobile accident or send over some poisoned food.” Agnes Meyer, a rival patron, stepped in and arranged for Mann to be appointed Lecturer in the Humanities at Princeton, with a full professor’s annual salary of $6,000, half financed by the Rockefeller Foundation. He’d have to give only three public lectures and three student classes on German literature, and would have plenty of time for his own work.

Mann, who had lost everything in Nazi Germany, earned money from his salary, lectures and American royalties. On September 28, with Newton’s help in finding the house and for $250 a month rent, he settled into 65 Stockton Street. The rather grand ten-bedroom, five-bathroom house had space for his six children when they lived with or visited him. Donald Prater described their home: “Secluded behind a brick wall and with mature pines and a dogwood, elegant and practical, it was more than ample for their needs… There were fine bedrooms (one to himself), a large library, vast reception rooms, and a separate studio already marked as his study, with the indispensible couch, while servants as well as a caretaker and washerwoman would be available.” His wife Katia, his oldest daughter Erika, the German refugee Hans Meisel and Molly Shenstone, the wife of a Princeton professor, made his life as pleasant as possible by providing secretarial help, translating his work into English and dealing with his massive correspondence.

On October 19, three weeks after settling into these luxurious surroundings, Mann — who’d lived in splendid homes in Lübeck and Munich — sent his favorable first impressions. He encouraged his Jewish friend, the literary critic and cultural historian Erich Kahler, to move from England to Princeton: “Our house, which belongs to an Englishman, is very comfortable and an improvement over all those of the past… The people are well-meaning through and through, filled with what seems to me an unshakable affability… The landscape is parklike, well suited to walks, with amazingly beautiful trees which now, in Indian summer, glow in the most magnificent colors.”

Though Mann occasionally felt a nostalgic longing for Switzerland, he recreated his European life in America. He was committed to write in exile — though his books had been burned in Germany and he’d lost most of his readers — and to oppose the Nazi regime. He also told Kahler that he’d reassembled his small clock, calendar, letter opener and pen holder: “my desk stands in my study with every item arranged on it exactly as in Küsnacht, and even in Munich. I am determined to continue my life and work with maximum persistence, exactly as I have always done, unaltered by events which injure but cannot humiliate me or turn me from my purposes.”

His oldest son Klaus was surprised by the elegance of the huge house. By contrast, his second daughter Monika felt the servants were lax, and the Gothic elements reminded her “of a haunted castle, with its overgrown garden, weathered walls, creaking stairs, and the large high-backed chairs covered with red damask in dimly lit rooms which should really have been guarded by a sinister-looking lackey.”

Princeton treated Mann as a distinguished guest who brought great prestige to the university. In May 1939, at the end of his first academic year, they awarded him an honorary doctorate. He recorded in his Diaries: “Donned academic gowns in the president’s office. Procession into the very dignified hall, a good-sized audience. Katia up front with the two sons and [daughter Elisabeth]. Speech by the dean, some Latin words from the president, presented with my hood. Speech by [President] Dodds praising my academic activity and expressing his wish that I continue it. Then my speech. Spoke well.” Two days later in a letter to Agnes Meyer, Mann expressed his high-spirited response to America and contrasted it to the more formal manners of Switzerland: “it is a blessing to me to sink roots into this soil, and every new tie confirms me in my feeling of being at home… I find people here good-natured to the point of generosity in comparison with Europeans, and feel pleasantly sheltered in their midst.”

During the summer of 1939 Mann spent three-and-a-half months in Europe. Like Gustav von Aschenbach in Death in Venice, he was calmed by the sound of gentle waves and liked to write at the seaside. Cocooned in a sheltered beach tent or a high wicker basket on the North Sea coast of Holland, he continued as always to compose. He visited his publishers and son Golo in Zurich, his daughter Monika in London, and went to Stockholm for the PEN Congress that was cancelled when World War II broke out on September 1. Grateful for his safe return on a ship crowded with refugees, he called his arrival a “homecoming — of a sort. America my fated berth and refuge, perhaps for the rest of my life; there is much talk of the ‘war’ lasting ten years.”

Mann’s Princeton house became a congenial meeting place for many distinguished European refugee writers, scholars and political allies, including W. H. Auden, Erich Kahler and the Austrian-Jewish novelist Hermann Broch. Klaus Mann recalled that guests from Princeton and New York “rarely came en masse but rather singly or in little groups… among them Albert Einstein with his beautiful silver mane, domed forehead and wily piercing glance.” Mann wrote that Broch, who would live in Kahler’s house from 1942 to 1948, “gets a measure of comfort in Princeton from being near his fellow-countrymen, who, though unable to do very much for him, prevent his being too unbearably lonely.” After reading Mann’s masterful Doctor Faustus (1947), Broch told Kahler that he was “full of terrible feelings of inferiority when I see the stupendous energy this old man puts into his work. What he managed to achieve while completing Faustus!”

In the foreword to his political speeches Order of the Day (1942) Mann wrote that he would never forget, when Neville Chamberlain capitulated to Hitler in Munich in September 1938, “how broken Albert Einstein’s voice sounded when he spoke to me over the phone on my arrival in Princeton [and said] ‘I have never in my life been so unhappy’.” The old friends met frequently for meals at each other’s homes. In their photo Einstein, sitting on a chair with fingers entwined in his lap, wears a speckled woolly grey jacket buttoned up to the neck. He has wild white hair, high forehead and black mustache, and looks down while slightly smiling and listening intently to Mann. Dressed more formally in a dark tie and business suit, and with flattened dark hair, Mann holds a white paper in his hand, turns to the right and speaks to Einstein. On Einstein’s death in April 1955 — four months before Mann died in August — he was deeply shaken and offered an eloquent tribute to their friendship: “I am at the moment able to say only that through the passing of this man, whose fame even during his lifetime had taken on a legendary character, a light has been quenched for me, which had been a comfort for many years in the dark confusion of our times.”

Mann’s two prominent patrons, Agnes Meyer and Caroline Newton, were rivals for his attention, affection and gratitude. Both were fluent in German, extremely rich, usefully influential, generous with gifts, devoted, possessive and even (especially Agnes) in love with him. He had to be sure to keep them apart when their dates to see him clashed, and found their projected but fortunately never finished biographies of him both fatiguing and boring. Meyer was Jewish, born in New York, educated at Barnard College and the Sorbonne, married and with five children. Newton was gentile, born in Philadelphia, the daughter of the industrial magnate and famous book collector A. Edward Newton. Educated at the Columbia University School of Social Work, she was unmarried and six years younger than Meyer.

The formidable Agnes Meyer (1887-1970) was the intellectual and philanthropic wife of the powerful, multimillionaire owner of the Washington Post. She had a large forehead, widely spaced eyes, long nose and thin lips. The daughter of German émigrés, she frequently corresponded with and entertained Mann in her luxurious city and country mansions in Washington and in Westchester County, north of Manhattan. She translated and publicised his speeches, reviewed his books and planned to write what he considered an intrusive book about him. Obliged to pile on the compliments, he called her first draft a “delicate and helpfully interpretive effort of a noble feminine spirit.” She also criticised and tried to translate his novels, objected to his political views when he attacked American neutrality and (as the former lover of the French poet and ambassador Paul Claudel) even tried to seduce him. Meyer also provided many valuable services. She introduced him to high-ranking government officials, and used her considerable influence to get him lucrative positions at Princeton and the Library of Congress. On December 25, 1940, her gift of a richly brocaded dressing gown inspired a moment of rare humor. Mann told her that the elaborately costumed “Richard Wagner would have paled with envy at the sight of it.” But he feared that taking it on his travels would make him look wealthy and increase his hotel bills.

But Meyer was a bountiful tyrant. Mann courted and flattered the indispensable patron in his letters, but tried to keep her at a tolerable distance. He did not want to arouse unreal expectations nor antagonize her. He recorded in his Diaries how much he dreaded her all-too-intimate visits and hated their stupid and humiliating friendship. But he was unable to disguise his true feelings, and Meyer told his son Golo that it was clear from Mann’s letters that he really despised her. Thomas then wryly wrote Golo, “since these letters are full of devotion, admiration, gratitude, concern, even gallantry, that is a very intelligent observation.” Their troubled relations reached a crisis in May 1943 when Mann was well established and needed less help from her. Weary of bending the knee and swallowing the toad, he could no longer bear her officious meddling and tried (unsuccessfully) to sever their relations. “Nothing was right, nothing enough,” he complained, “you always wanted me different from the way I am. You had not the humour, or the respect, or the discretion to take me as I am. You always wanted to educate, dominate, improve, redeem me. In vain, I warned you.”

Caroline Newton (1893-1975) did postwar social work for the Quaker-affiliated American Friends Service Committee in Vienna and, though not a medical doctor, was a member of the local Psychoanalytic Society. She was also a patron of Auden, whose friend Charles Miller called her “short, plump and round-faced with lots of loose brown hair, graying. Despite her furs and expensive clothing she managed to look disheveled… blinking behind glasses.” Auden’s biographer described her demanding and irritating character: “She had been psychoanalysed by both Freud and Karen Horney, but despite setting up in psychiatric practice herself she remained a neurotic and even risible figure. She was a generous if emotionally exacting patron; she gave cash, hospitality and gifts but was self-absorbed, histrionic and self-important.” Though supposedly well informed about Mann, she absurdly claimed — despite Dr. Krokowski’s Freudian lectures in The Magic Mountain (1924) — that she’d introduced Mann to Freud’s work and that he “had not only never read a line of Freud, but was not even familiar with his name in 1924.” In 1929, the year they met, Mann had already published his first essay on Freud.

Newton offered Mann her luxurious summer “cottage” on the coast of Jamestown, Rhode Island, for the duration of the war. But he lived there only from late May through June 1938. Though he normally liked to write near the sea, he was bored by the monotonous life, felt buried in “nature” and was plagued by insects. Newton redeemed herself by giving the doting dog-lover a welcome gift. He wrote Meyer, to arouse her competitive instinct, “For a few days now we have had a charming black poodle of French background — a gift from the biographer Caroline. We call him Nico. He disturbs me terribly, but I loved him at first sight.” Nico, unlike Mann, had difficulty settling in and caused problems at first. He effectively reduced Mann’s library by chewing up a philosophical book by Ernst Cassirer and also frightened his master by running away. Mann wrote that “in an unsupervised moment he jumped through one of the low windows of the dining room into the garden, and raced out through the gate.” Hotly pursued and captured by the elderly panting Mann, he was forgiven and “likes to lie on my foot under the desk” — a privileged position granted to no one else in the household.

Recognising the symbolic as well as the literary importance of his work in exile, Mann wrote every day with amazing tenacity and iron discipline, in hotels, ships and trains, while traveling, lecturing and on holiday, even when he was ill. He declared, in a letter to Meyer, his passionate commitment to his art: “[Do not doubt] my doggedness, and the obstinacy of my habits. How should I not work? I know no other way, and shall go on as long as I live” — and he did. In a valuable letter of March 1940 he gave an unusually long and precise description of his writing habits:

“For many years I have done my serious writing, that intended for publication, almost exclusively during the morning hours, from nine to noon or half past twelve. I work by myself and write by hand… About one and a half manuscript pages constitute my daily stint. This slow method of working springs from severe self-criticism and high requirements in matters of form, but also from the ‘symbolic content’ of style, in which every word and every phrase counts…”

“Much of my composition has been conceived on walks… For writing I must have a roof over my head… For a longer book I usually have a heap of preliminary papers close at hand during the writing; scribbled notes, memory props, in part purely objective — external details, colourful odds and ends — or else psychological formulations, fragmentary inspirations, which I use in their proper place.”

His carefully composed first draft, with very few revisions, was sent directly to the printer. From 1938 to 1940, during his astonishingly creative Princeton years, Mann wrote a long introduction to Schopenhauer’s work; effective political propaganda: Achtung, Europa!, The Problem of Freedom, The Coming Victory of Democracy, This Peace, This War and his BBC broadcasts starting in 1940 and published in Listen, Germany!(1943). He also completed his Indian-myth novella The Transposed Heads.

In December 1938 he resumed work on his Goethe novel — called Lotte in Weimar in German and The Beloved Returns in English — and told his publisher, “I pursue her every morning a bit further, as far as the demands permit which this country, in its naïve enthusiasm, places upon me… Kahler was so impressed with the first twenty-five pages, which I recently read to him, that he went so far as to use the word ‘magnificent’.” When reading in German to appreciative friends and family, Ronald Hayman noted, “his voice was sonorous, his delivery steady and distinct, the timbre constantly undulating,” with each syllable given a precise value. Mann said the theme of the novel, in which Goethe’s youthful love, the heroine of The Sorrows of Young Werther, visits him in old age, is “recurrence, enhanced by awareness, though at the sacrifice of some vitality.” The precious manuscript was sent from America to Portugal in a Swiss diplomatic bag and from there in a Swedish plane to his exiled publisher in Stockholm.

Conscientious as always, Mann took his Princeton teaching seriously. Between January 1939 (three months after he arrived) and May 1940, he gave public lectures in English on Wagner’s Ring, “Freud and the Future” and Goethe’s Faust. He also spoke to students on modern German literature, on his own career (later published as A Sketch of My Life) and on The Magic Mountain. He told the students that the heroine of that novel, “Madame Chauchat, is seductive first of all in a sense that I should not like to object to, and secondly, as Settembrini sees it, a little in an intellectual sense as well.” He wrote to his older brother Heinrich, with underlined words in English, “I must prepare lectures for the boys on the art of the novel, my major effort consisting in not doing the thing too well.” He did not want to confuse his unfamiliar audience by speaking above their heads. He and Einstein also spoke to theology students in the university chapel, and he gave a speech after the award of his honorary doctorate. His teaching was well received and his appointment was renewed for the spring semester of 1940.

Aged 63 to 66 during his Princeton years, Mann spoke in all the major cities and universities in America, from a tumultuous crowd of 18,000 at Madison Square Garden in New York to minimal audiences in remote outposts like the high school in Topeka, Kansas and the State College for Women in Denton, Texas. Erika, his secretary and assistant, came along with Mann and Katia. He read her English translations in a deep voice, rolling his “R’s” with a strong German accent. Erika translated questions from the audience and gave the gist of his replies in English. His agent Harold Peat, who’d lost his right arm as a Canadian private in World War I, had many eminent clients including Lillian Hellman, H. G. Wells and Winston Churchill. Peat’s Speakers Bureau took fifty per cent of Mann’s fee, usually about $1,000 for each lecture.

In May 1939, three months before the outbreak of the war, Mann confirmed his political commitment and wrote to Franz Werfel, “together with our own proper and personal tasks, together with the ‘demands of the hour’ and beyond them, we are duty-bound to use our influence on the Germans.” His annual three-week lecture tour in March 1939 ranged from Boston to Seattle. The following year, in February 1940, he hit the road again from Delaware, Ohio to Houston, Texas. His anti-Nazi propaganda speech, The Coming Victory of Democracy, broadcast throughout the United States, explained the political, moral and artistic reasons for predicting the defeat of fascism. His rousing talk urged Americans to abandon neutrality. A few months later he pressed them to join the Allies in the war against Hitler.

Mann knew America from coast to coast better than any émigré writer and reached an audience of 60,000 on his lecture tours. He knew the drill and was pleased by the excellent beds in his private train compartments. But the strain of cross-country journeys, incessant interviews, tedious photography sessions, piles of books to sign and repetitions of the same lecture was exhausting. The formal patrician writer was bored by the endless meaningless chatter with effusive strangers. Wherever he went the hosts demanded the maximum effort from their illustrious captive. “These Americans certainly know how to bleed you dry,” the aged traveler complained to Meyer, “not to say grind you down; they themselves have no nerves at all, and it never occurs to them that someone else might tire. One party lasted literally from six to one o’clock: dinner, followed by a mass reception” that left him half dead before pressing on to his next engagement.

After these lucrative but tedious tours, Mann had mixed but mostly positive feelings about America. Comparing the country to Europe, he observed, “In spite of a certain primitivity, lack of nerve and simplicity [about the war], it is a proper, well-meaning country, with a positive longing for what is good and right.” After the Nazis revoked his nationality, he traveled on a Czech passport, but in August 1939 he received his first American citizenship papers. With no university degree, he had harvested six honorary doctorates with more on the way, and was a corresponding member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. But in San Antonio, Texas, he noticed the numerous Mexicans, a “most attractive type and a relief after the eternal Yankeedom.” Confirming Scott Fitzgerald’s lament in The Crack-Up (1936), “There were no second acts in American lives,” Mann shrewdly commented that “success is a stern god in America, almost as stern as failure… Here in America the writers are short-lived; they write one good book, follow it with two poor ones, and then are finished.”

Mann’s prestige and authority were greatly enhanced by his invitation, with Katia and Erika, to stay overnight at the White House in January 1941. (He had previously attended a White House dinner in June 1935.) “The dizzying height was the cocktail in the study,” he proudly wrote, “while the other dinner guests had to cool their heels below.” His perceptive analysis of Roosevelt, a “wheelchair Caesar,” concluded that the president had a “mixture of craft, good nature, self-indulgence, desire to please, and sincere faith.” That same month Mann optimistically stated that his strenuous efforts had been productive and that America “is just beginning slowly, slowly, against ponderous resistance… to come to an understanding of the situation and the pressing necessities of the times.”

While Mann was writing in Princeton and lecturing in America the political events in Europe were disastrous. From September 1938 to June 1940 there was the Chamberlain-Hitler betrayal of Czechoslovakia, the occupation of the German-speaking Sudetenland, the pogroms against the Jews on Kristallnacht, the fascist victory in the Spanish Civil War, the German-Russian non-aggression treaty, the invasion of Poland, the start of World War II and the fall of Paris. Hitler’s armies seemed invincible and all of Europe would soon be occupied by the Nazis. The turning point of the war did not occur until the Allied victories at Stalingrad and Alamein in the winter of 1942-43.

In December 1938 Mann explained, “We have adjusted well to our new surroundings. Outward conditions have been good, but our minds troubled… the events in Europe have been a great burden and source of anxiety.” In retaliatory propaganda, the Gestapo newspaper reported that Mann had physically deteriorated and was begging, half starved, in Paris cafés. Mann recorded in his Diaries, April 1939, that influential friends “consider it a foregone conclusion and unavoidable that I would have to be president [of Germany] after Hitler’s fall.” This became a real possibility when the war ended, though Mann wanted to concentrate on his writing and refused the honor.

Since Mann had luckily escaped from the Nazis — who certainly wanted to kill him — and settled securely in America, he felt obliged to use his considerable influence to assist other writers who were still in danger. He saved many lives while helping Alfred Döblin, Franz Werfel, Robert Musil and many others to flee from Europe. He got Max Brod, Kafka’s closest friend, a job in America just before Brod decided to emigrate, carrying Kafka’s unpublished manuscripts, to Palestine. Recommending Kafka’s friend and doctor Robert Klopstock for a position at Harvard Medical School, he stated, “I first met [i.e. heard of] Dr. Klopstock through the gifted young German writer, Franz Kafka, for whom Dr. Klopstock did so much professionally and spiritually before he died.” In June 1924 Kafka’s agonised last words to Klopstock were, “Kill me, or else you are a murderer.”

Mann was very close to his large family, most of whom had affectionate nicknames. He was the Zauberer (magician), Katia was Mielein (little honey), Klaus was Essi, Gottfried was Golo, Elisabeth was Medi, Michael was Bibi. All six children wrote books and some were also talented actors, musicians and scientists. But all was not well from Mann’s point of view: one was lesbian, two were homosexuals and two sons committed suicide.

Erika, a lesbian, had previously married two homosexuals: the German actor Gustav Gründgens and, to obtain a British passport, the obliging poet Auden. In 1944, thrilled by the transgression, Erika began a wild love affair with the much older married conductor Bruno Walter. He was a close friend and the same age as Mann as well as the father of Gretel, Erika’s childhood friend in Munich. An even more bizarre episode took place in Zurich on August 18, 1939 during Mann’s second year at Princeton. Gretel was having a love affair with the handsome Italian opera star Ezio Pinza, who had performed brilliantly and appropriately in “Don Giovanni”. While she was sleeping that night her jealous husband, the Austrian film producer Robert Neppach, murdered her and then shot himself.

In 1939 Mann’s son Michael married a Swiss woman, Gret Moser, the childhood friend of Mann’s daughter in Zurich; Monika married the Hungarian art historian Jenö Lányi; and his brother Heinrich married his second wife, the barmaid and prostitute Nelly Kröger, whom Mann hated. His favorite child, Elisabeth, who was exceptionally close to him, fell in love with the divorced Sicilian Giuseppe Borgese, a professor of political science at the University of Chicago. Thirty-six years older than Elisabeth and only seven years younger than Mann, he was — like Bruno Walter with Erika — clearly a replacement for her father. Mann wryly noted, “Medi has married her anti-Fascist professor, who at the age of fifty-seven probably no longer expected to win so much youth. But the child wanted it and brought it off.” Mann felt he had lost his precious darling to an unworthy rival.

On his June 6, 1939 birthday Elisabeth failed to give him the traditional present. He felt “sorry for Medi, who was sharply scolded by Erika for her forgetfulness and was already shaken and confused, in tears.” But (like his poodle) she could do no wrong and he tried to soothe her. When Elisabeth was pregnant, Mann recalled, she was still “remarkably childish… The last time we took her for a walk with her great belly she asked me: ‘I wonder whether Mrs. Meyer will give me something for Christmas?’” It’s worth noting that all four children married non-Germans: English, Swiss, Hungarian and Italian. Elisabeth, and Michael’s wife, gave birth to Mann’s first grandchildren in 1940, and Michael’s son became the model for the angelic and doomed Nepo in Doctor Faustus.

Golo, after volunteering as an ambulance driver in wartime France, was interned as an enemy alien in a prison camp but managed to escape. He and Heinrich fled from occupied France, struggled through the high Pyrenees, reached Spain, flew to Lisbon and finally arrived in New York in October 1940. Monika was less fortunate than Golo. On September 18, 1940, she was sailing on the passenger ship City of Benares, which was carrying ninety children and their nine escorts from England to safety in Canada. That night the ship was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine, 600 miles out in the Atlantic. Nearly 300 passengers and crew were killed and only seven children survived. Monika remained alive by clinging to a piece of wood in the heavy seas for twenty hours, but saw her husband drown before her eyes. Two important novels alluded to this infamous war crime. At the beginning of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) Winston Smith watches a newsreel that shows the sinking of this refugee ship and provokes a howl of rage from the audience. In The Battle Lost and Won (1978), the second volume of Olivia Manning’s Levant Trilogy, the actor and military officer Aidan Sheridan, escorting these children, was traumatised when the ship was torpedoed and most of them were killed.

After his third year at Princeton, Mann decided to give up teaching and ironically wrote, “I don’t think even if we stay here, that I shall let myself in for such amusements again. I must be free for the 4th volume of Joseph,” which would match the four parts of Wagner’s Ring. Agnes Meyer eased the transition by procuring an undemanding position as Consultant in Literature at the Library of Congress. Preferring the “movie mob” to the scholarly atmosphere of Princeton, in the spring of 1941 he moved to Los Angeles, which had a stimulating group of German émigrés.

In Los Angeles, Mann resumed his friendship with the Englishman Christopher Isherwood, who was fluent in German and knew Mann better than any Anglophone author. He and Auden — Mann’s official son-in-law — had emigrated to America in January 1939 and were Mann’s guests in Princeton on February 1st. In July 1940, when Mann was looking for a house in California, Isherwood gave the most perceptive description of his character during these troubled years:

“Thomas was urbane as ever. If the English saved democracy, he said, he would gladly tolerate all their faults, even the Oxford accent… He looks wonderfully young for his age — perhaps because, as a boy, he was elderly and staid. With careful, deliberate gestures, he chooses a cigar, examines a cognac bottle, opens a furniture catalogue — giving each object his full, serious attention. Yet he isn’t in the least pompous. He has great natural dignity. He is a true scholar, a gentlemanly householder, a gracefully ironic pillar of society — solid right through.”

When Mann died in Switzerland in August 1955, Isherwood wrote a warm and heartfelt response that contrasted to Mann’s rather formal tribute to Einstein: “He was lovable in a tiny, cozy way — he was kind, he was genuinely interested in other people, he kept cheerful, he was gossipy, he was quite brave.”